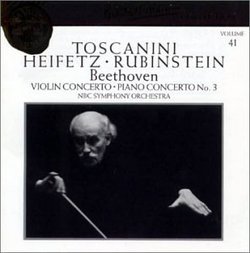

| All Artists: Beethoven, Rubinstein, Heifetz, Toscanini, NBC Title: Violin & Piano Concertos Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 1 Label: RCA Release Date: 5/25/1990 Genre: Classical Styles: Forms & Genres, Concertos, Historical Periods, Classical (c.1770-1830), Modern, 20th, & 21st Century, Instruments, Keyboard, Strings Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 090266026128 |

Search - Beethoven, Rubinstein, Heifetz :: Violin & Piano Concertos

| Beethoven, Rubinstein, Heifetz Violin & Piano Concertos Genre: Classical

![header=[] body=[This CD is available to be requested as disc only.]](/images/attributes/disc.png?v=15401716) ![header=[] body=[This CD is available to be requested with the disc and back insert.]](/images/attributes/disc_back.png?v=15401716) ![header=[] body=[This CD is available to be requested with the disc and front insert.]](/images/attributes/disc_front.png?v=15401716) ![header=[] body=[This CD is available to be requested with the disc, front and back inserts.]](/images/attributes/disc_front_back.png?v=15401716) |

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsHistorical Discophage | France | 12/27/2009 (5 out of 5 stars) "When I was younger and knew less (not that I now know much that really matters), I thought (like many others I believe) that Heifetz and Toscanini played everything too fast, and too relentlessly. My ideal in Beethoven's Violin Concerto was the long breath and sweet lyricism of Oistrakh (his third and last studio recording, with Cluytens and the French National Orchestra, in 1958, Beethoven & Bruch: Violin Concerti (Oistrakh)).

Well, I certainly haven't reneged on Oistrakh, but then came the "historically-informed" interpretations and the ear-cleansing approaches of Norrington, Gardiner and the likes. And I reflected on matters of tempo in interpreting Beethoven, and more generally in the interpretation of 19th Century music by performers from the second half of the 20th Century. As much as I (still) like the long breath, I also like it when performers play what the composer has written - which is, if the printed score is to give any indication thereof, also what he intended. Not that other approaches can't be illuminating and convincing, but some times the "commentary", or the accepted traditions, simply blurr the original image, like the patina on Michelangelo's murals in the Sistine Chapel (paiting conservators call it "dirt"). The tendency in the 2nd half of the 20th Century has been to slow down the tempos, in order (presumably) to bring out the expressivity, the pathos, the grandeur, the weight, the "angst" and anguish, the lyricism, the "hidden layers" and what not. But oftentimes the forward momentum, the exuberance, the explosiveness, the youthful joy - and simply the score's tempo indications - are lost in the process. Beethoven's Violin Concerto is a good case in point. OK, granted, the tempo indication for the first movement does allow for a wide margin of, well, interpretation: "allegro ma non troppo". So how much the "allegro" is going to be watered down by the "non troppo" is up to the interpreters. Still, I find that many recordings are more a "moderato" or a "maestoso" than anything close to an allegro, even with the "non troppo" gear clinched. Likewise with the second movement (Larghetto should be more flowing than a Largo) and the finale (Rondo allegro - why turn it into a trudging peasant dance - and why should peasants in the time of Beethoven dance so trudgingly?). It is surprising that Heifetz should have waited as late as 1940 to record Beethoven's VC. I don't know if it had to do with the public's tastes in those days or his own. He made a famous remake early on in the LP era with Munch and Boston in 1955 (Heifetz Plays Beethoven & Brahms). As for Toscanini, this is a significant testimony, as it is the only recording he made of a piece he often conducted in concert (and this occasion was the last time he performed it as well). So, Heifetz and Toscanini are swift. Toscanini is also powerful and muscular - you recognize that the Concerto was written in the same year as the Eroica - although the orchestra's articulation could be crisper. Heifetz doesn't linger and grind to a near-halt to let you enjoy the view; he is far from being inflexible, but his rubato is minimal, discreet and tasteful. As a result, his and Toscanini's approach by no means lacks lyricism, but the pulse is by the bar rather than by the beat, and you always have the sense that they know where the phrase is leading to when they board it. Heifetz' not big and plush but crystalline and razor-sharp tone is perfect - now here's a man who, even at those fast tempos, knew how to sing. He plays his own reworking of Auer's and Joachim's cadenzas. Sonics are 1940 78 rmp; there is some saturation in the finale, and you can hear the side joint at 8:09 in the first movement - the sound of the orchestral tutti suddenly jumps at you. But the instruments are well defined and Heifetz' tone is stellar. The 1955 recording comes in stupendous sonics that sound, I don't know by what technical miracle, as stereo as anything recorded ten years later, but I find that Heifetz' marginally more high-strung approach in the first movement goes one step too much over the top, and changes breath into suffocation. So this earlier effort is, sonic warts and all, my prefered version of the two. The liner notes, by the eminent Toscanini specialist Mortimer H. Frank, mention Rubinstein's recollection of the rehearsal of this live concert and NBC broadcast of Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 3 from October 29, 1944, the only collaboration between the two and the maestro's first performance of the Concerto in the US (there is available, but not part of the official RCA Toscanini edition, another recording of it, made two years later with Myra Hess, Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 3; Wagner: Siegfried's Rhine Journey from Gotterdammerung). The first run-through had not gone well, apparently because of the significant differences of conception between conductor and soloist, but then Toscanini asked a sceptical Rubinstein if he would play the first movement again, and suddenly all was in place, "the tempo was right... and the tutti sounded with all the nuances required... Toscanini... respected all my dynamics, held up the orchestra where I made the tiniest rubato...". If this leads you to think that Toscanini significantly changed his conception to fit the soloists, it is not what I hear; the two approaches must not have been so wide apart. It is a reading of considerable dynamism, forward momentum, crisp articulation and bubbling energy. The Rubinstein-Heifetz-Piatigorsky collaboration of the 1940s is often presented as a purely financial affair from soloists who shared little in common musically, but from the Rubinstein recordings from those years (including his recordings with Heifetz, see my review of Jascha Heifetz Recital), I don't hear that at all. Rubinstein was not in those years a "mellow" pianist, as this Beethoven 3rd amply proves. There are small patches of sonic distortion in the finale and a constant, underground grating from the shellac surfaces - nothing significant in view of these two recordings' historical importance and musical value." |

Track Listings (6) - Disc #1

Track Listings (6) - Disc #1