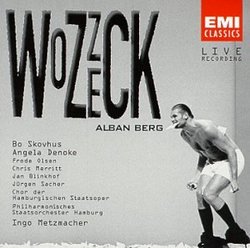

| All Artists: Alban Berg, Bo Skovhus, Agnela Denoke, Ingo Metzmacher, Philharmonisches Staatsorchester Hamburg, Frode Olsen, Chris Merritt Title: Alban Berg: Wozzeck / Ingo Metzmacher Members Wishing: 2 Total Copies: 0 Label: Angel Records Release Date: 11/5/2002 Album Type: Import Genre: Classical Style: Opera & Classical Vocal Number of Discs: 2 SwapaCD Credits: 2 UPC: 724355686527 |

Search - Alban Berg, Bo Skovhus, Agnela Denoke :: Alban Berg: Wozzeck / Ingo Metzmacher

| Alban Berg, Bo Skovhus, Agnela Denoke Alban Berg: Wozzeck / Ingo Metzmacher Genre: Classical

Wozzeck was composed by Alban Berg in the 1920s, and it uses as a libretto, virtually unchanged, a play that had been written almost a century earlier (and was later made into a film by Werner Herzog). But it is a shocking... more » |

Larger Image |

CD Details

Synopsis

Amazon.com

Wozzeck was composed by Alban Berg in the 1920s, and it uses as a libretto, virtually unchanged, a play that had been written almost a century earlier (and was later made into a film by Werner Herzog). But it is a shockingly modern work that hits 21st-century audiences with an impact like a tabloid headline: "GI SLAYS MATE, SELF." The opera takes place in a constant atmosphere of near-hysteria. Based on a real incident, it tells the story of a life of quiet desperation breaking down in an outburst of sudden, deadly violence. Wozzeck, a soldier at the bottom rank of the military pecking order, is a chronic loser, ridiculed by his captain, subjected to degrading experiments by the camp doctor, beaten by a bully who steals his lover. He is pushed into a situation where death seems the only possibility. The music, mostly atonal but occasionally making powerful use of tonality, creates its own hallucinatory universe. Tightly disciplined in form and intensely atmospheric, it makes extreme, sometimes heroic demands on the singers' expressive abilities and the orchestra's technical skills. It also tests an audience's ability to absorb shocks, though it must have been even more shocking in 1925 than in the era of gangsta rap. Considering the challenges it poses both for performers and for audiences, it is remarkable that Wozzeck has fared so well on records, but this Hamburg Opera recording has been preceded by a half-dozen others. None are flawless, but all have something to recommend them. Among those currently available, two (conducted by Dmitri Mitropoulos and Claudio Abbado, respectively, are particularly commendable. This production, conducted by Ingo Metzmacher--general music director at Hamburg Opera--can take its place with them at the top of the list. Bo Skovhus brings to the title role the best voice it has had on records since Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. Vocal beauty is not a primary requisite for Wozzeck, but Skovhus also sings with intelligence, a sure sense of the role's range of moods, from inarticulate stolidity to superstitious anxiety and utter despair. Angela Denoke grasps the complexities in the role of Wozzeck's faithless mistress Marie, and supporting roles are vividly filled by Jan Blinkhof, Chris Merritt, and Frode Olsen. --Joseph McLellan

Track Listings (10) - Disc #1

Track Listings (10) - Disc #1