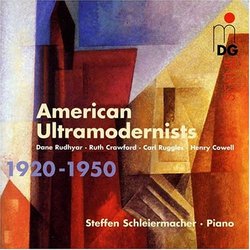

| All Artists: Dane Rudhyar, Ruth Crawford Seeger, Carl Ruggles, Henry Cowell, Steffen Schleiermacher Title: American Ultramodernists 1920-1950 Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: MD&G Records Release Date: 6/21/2005 Genre: Classical Styles: Chamber Music, Forms & Genres, Short Forms, Historical Periods, Classical (c.1770-1830), Modern, 20th, & 21st Century, Instruments, Electronic Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 760623126524 |

Search - Dane Rudhyar, Ruth Crawford Seeger, Carl Ruggles :: American Ultramodernists 1920-1950

| Dane Rudhyar, Ruth Crawford Seeger, Carl Ruggles American Ultramodernists 1920-1950 Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsA highly coherent program, but often stern, and a markedly s Discophage | France | 05/12/2007 (4 out of 5 stars) "It was a clever idea to bring together these four American avant-garde composers, or "ultra-modernists" as they called themselves then, active from the late 1910s onwards. The links between them are more than anecdotal. Rudhyar (born French under the name of Daniel Chennevière in 1895 and emigrated to the US in 1916) "developed theories of dissonance that were closely tied to ideas about spirituality and exerted a strong influence on several composers, particularly Carl Ruggles, Henry Cowell, and Ruth Crawford" (quote from Michael Broyles, "Mavericks and Other Traditions in American Music"). He is represented here by his 8th "Tetragram", Primavera, composed in 1928. "Rudhyar's closest bond during the early 1920s was with Carl Ruggles and Henry Cowell" (quote from Carol Oja, "Making Music Modern: New York in the 1920s"). As for Ruth Crawford, , then a student in Chicago, her encounter with Rudhyar in 1925 was "a definite turning point" and she fell entirely under his spell. Two Preludes from Crawford's set (composed between 1924 and '28) are particularly indebted to Rudhyar (the 6th "Andante mystico" and 9th "Tranquillo"), and in 1922 Cowell wrote a short (0'40) "Hommage a Rudhyar", one of the four compositions of his represented here. Ruggles' "Angels" and "Organum" are originally orchestral pieces; these piano versions are free arrangements made by pianist and scholar of Ivesian fame John Kirpatrick, imparting them a rugged austerity and granitic massiveness that heightens their kinship with the four "Evocations". All this makes for a particularly coherent program.

On the basis of the pieces played on this disc, three of these composers - Rudhyar, Crawford and Ruggles - share more than a few distinctive stylistic traits: a stark grandeur verging on the mystic, massive chordal writing, dissonant music that is serious, stern, meditative, not seductive. The counterpoint is more dissonant with Ruggles than Crawford (who in 1931 was to marry Charles Crawford, the composer and theoretician inventor of the concept of "dissonant counterpoint"). Now Cowell is something else. He is an inventor in sound, experimenting with tone clusters and piano string strumming, and his musical language, even in a piece as massively pounding as his 1924 "Piece for piano", is always entirely fascinating and highly seductive. Carol Oja, the author of the essential "Making Music Modern - New York in the 1920s", contributes the notes and seems to be the mastermind of this brilliant (but often stern) program. But the merits of the program are somewhat offset by the distant and muffled sonic perspective (you think you are listening from the next room), and also by the pianist's markedly slanted interpretive view. Checked against (the much better recorded) Sarah Cahill in Crawford's Preludes (Ruth Crawford: 9 Preludes, Johanna Beyer: Dissonant Counterpoint, Gebrauchs-Musik), Schleiermacher is rather heavy-handed in the more animated passages (there aren't many of them: Prelude # 2 "Allegro giocoso", parts of #3 "Simplice" and 9 "Leggiero"), and systematically adopts very slow tempos in the rest (compare his 4:25 in Prelude 6 "Andante mystico" to Cahill's 2:44, for instance). The approach can yield a convincing sense of mysticism (Prelude 5 "Lento" and 6) and stark grandeur (7 "Intensivo") but, applied to the complete cycle it doesn't offer much contrast and runs the risk of loosing the music's spine. The same is true with the Cowell pieces, always markedly slower than the composer's own readings (on Piano Music) and every one else's as well. Harp of life is played as a solemn procession - it is massive and mystic, but there's not much life. Likewise with Piano Piece, which Schleiermacher systematically plays one gear slower than the indicated tempos - Cowell's "Moderato" is played lento, "Allegretto" becomes moderato, "più presto" is "allegro moderato" - and "largo" is largo allright. It would be fine if it was a piece of Galina Ustvolskaya (Shostakovich's maverick, recluse and mystic pupil) but for a more faithful and dynamic rendition of Cowell's score, go to Cheryl Seltzer (Henry Cowell: Instrumental, Chamber and Vocal Music, Vol. 2). The approach works better in "The Snows of Fuji-yama", with its regular and slow pulse (far removed from Cowell's whimsical rubato) lending it a more dreamy and solemn character - a dream of Japan rather than the presence of Japan. Ultimately, it is to Ruggles' stark grandeur that the approach seems best suited, although Donald Berman (The Unknown Ives) proves that the last piece of this cycle, "Adagio Sosetnuto", doesn't need to be as boring as Schleiermacher makes it sound. I made these discographic comparisons after the first publication of this review. Had I made them before, I would have rated it only three stars. In sum, this is probably not the version to have if it is your first introduction to these pieces. The references given in this review are better choices, and among them Cowell's recording of his own piano music is belongs to any half-way serious collection of 20th century music. " |

Track Listings (23) - Disc #1

Track Listings (23) - Disc #1