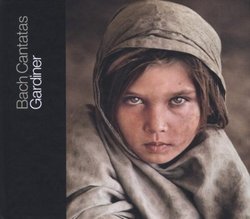

| All Artists: Johann Sebastian Bach, Sir John Eliot Gardiner, The English Baroque Soloists, The Monteverdi Choir, Lisa Larsson, Ruth Holton, Daniel Taylor, Nathalie Stutzmann, Christoph Genz Title: Bach: Cantatas, Vol. 27, Blythburgh/Kirkwall Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: SDG - Soli Deo Gloria Release Date: 4/8/2008 Genre: Classical Styles: Opera & Classical Vocal, Forms & Genres, Concertos, Historical Periods, Baroque (c.1600-1750) Number of Discs: 2 SwapaCD Credits: 2 UPCs: 843183013821, 884385612108 |

Search - Johann Sebastian Bach, Sir John Eliot Gardiner, The English Baroque Soloists :: Bach: Cantatas, Vol. 27, Blythburgh/Kirkwall

| Johann Sebastian Bach, Sir John Eliot Gardiner, The English Baroque Soloists Bach: Cantatas, Vol. 27, Blythburgh/Kirkwall Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsGardiner does it again Teemacs | Switzerland | 04/27/2008 (5 out of 5 stars) "I've long waited for this one. BWV129 is an old favourite - I love the old Rilling recording, with the three trumpeting Läubin brothers blowing up an absolute storm, soaring and trilling likes things possessed. Naturally one can't expect this with natural valveless trumpets. And Gardiner's forces pull it off magnificently, in a wonderful atmospheric acoustic (St. Magnus's Cathedral, Kirkwall in the Orkneys). And this in spite of the difficulties in getting there (Gardiner and Co. were stuck at the airport when a substantial chunk of the UK air traffic control system fell in a heap) and the consequent short rehearsal time. A nice and unusual touch is a performance of Brandenburg Concerto No.3. Why? Because they were running out of Trinity cantatas to play, so they included the "trinity" concerto - 3 violins, 3 violas, 3 cellos, in one of Bach's most loved instrumental pieces." GETTING TO KNOW BACH DAVID BRYSON | Glossop Derbyshire England | 05/03/2008 (5 out of 5 stars) "This leg of the Bach cantata pilgrimage starts with a short trek across Suffolk from Long Melford to Blythburgh church for Whit Tuesday, and then a longer excursion for Trinity Sunday to the Orkneys, a trip of a kind familiar to air travellers in Britain and recently re-enacted on a grand scale at Heathrow's Terminal 5. The date was in the year 2000 of course, and the air traffic control computer had broken down. Whether at that date the entire congested air traffic over southern England was still controlled by a single small and antiquated PDP11 minicomputer I cannot now remember. I found out about this, of course, from Gardiner's 'blog' that accompanies every step of his and his colleagues' epic journey, and it reinforced my astonishment and awe at the sheer poise and professionalism that these artists display on every occasion, even when they have lost a day from their already short rehearsal time.

Interesting and enlightening as Gardiner unfailingly is, in this instance my attention was captured even more by the short essay from Paul Agnew, who takes the tenor solos on the Trinity Sunday disc. In brief, Agnew is a professional musician who thought he knew Bach because he knew the Passions, the 48 and the concertos. Not only did he not know the cantatas, which he now hears as the core of Bach's output, most professional musicians, he tells us, did not know them either so recently as 2000. This eases my own sense of guilt at being so late in becoming acquainted with them, but it further enhances my amazement at what this pilgrimage is achieving. The music that they present to us with not only such affection and understanding but with such command and aplomb even in difficult circumstances is not Beethoven symphonies: it seems to have been music that they were learning as they went along. Only two cantatas for Whit Tuesday survive, so to fill out the first disc there is a performance of the third Brandenburg concerto, a choice that suggested itself naturally because a modified version of its first movement had been a 'sinfonia' in one of the cantatas the group had just been giving at Long Melford. Bach provides no central slow movement for this concerto, only a pair of cadential chords. Something has therefore to be supplied, and here we are offered the interesting and unusual choice of an unaccompanied violin solo taken from the prelude to Bach's first sonata for that instrument. Without having taken the trouble to verify the matter, I think this may be an abbreviated version, but its main interest is in its unexpectedness and originality, although I would have liked to be told who was actually playing. Starting as it does with an instrumental number, this set inclines me to focus the review more than I have done elsewhere on the instrumental side of the performances. Bach thought of music in instrumental much more than in vocal terms, I'm quite convinced. Even when he is setting a text for singing, Bach is inspired to turn out another of his infinitely varied and infinitely expressive musical patterns just as he might do for a purely instrumental composition, and the voices are integrated into an instrumentally-focused abstract design. One excellent point that Agnew makes is how vivid Bach's orchestral colouring is -- he can work wonders in the six cantatas here with a couple of oboes, or a pair of recorders, or a trio of trumpets. Add timpani to these last and we have a wonderful and exhilarating sound in the final cantata no 129, and I am as baffled as Gardiner apparently was that it failed to arouse the expected enthusiasm among the Orcadian audience. One detail in Gardiner's account left me unclear regarding the instrumentation, and it is whether they managed to obtain a 5-stringed violoncello piccolo for cantata 175 or whether a more normal kind of instrument had to do. The names of the soloists are becoming familiar to me as I progressively follow in the steps of their pilgrimage, and they perform to the magnificent standard that continues to astonish me without surprising me, so confidently have I come to expect it by now. Not least impressive is Paul Agnew himself, whose exceptionally interesting comments I have already mentioned. He sings with the fervour of a lover with a new musical love. I am with him in his enthusiasm wholeheartedly, and although I fully join in the extravagance of his admiration for Bach I would only suggest that 'dramatic' is not one of the words to praise him with. Bach's wonderful musical patterns can be vivid, they can be overwhelmingly powerful, but it still seems to me that Bach's mind is contemplative even when his music is most overpowering. There is no paradox in this perception. All that the composer requires for it to be true is an infinite musical gift. As I acquire more of this marvellous series I am coming to think of it as a unity more than as a series of separate productions, and although each disc has to be assessed separately from the others I am finding that the assessment tends to be much the same every time. Similarly with the cantatas themselves. I find them less a series of freestanding works like, say, Beethoven's sonatas than a great unified river of inspiration whose source is Bach's unshakable faith allied to his limitless talent. The age I have lived through has brought this to me through the agency of not only the artists but the technicians, whose work has been of an undeviatingly high standard. A word of thanks also to the aviation industry for delivering the pilgrims safely, and perhaps a quiet reminder that modern propeller airliners are often much newer than they look and are technologically impressive, deserving a kinder name than 'crop-sprayers'." |

Track Listings (16) - Disc #1

Track Listings (16) - Disc #1