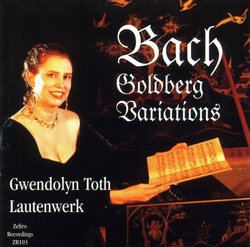

| All Artists: Johann Sebastian Bach, Gwendolyn Toth Title: Bach: Goldberg Variations Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Fountainbleu Ent. Original Release Date: 1/1/2000 Re-Release Date: 9/16/2003 Genre: Classical Styles: Chamber Music, Historical Periods, Baroque (c.1600-1750), Classical (c.1770-1830) Number of Discs: 2 SwapaCD Credits: 2 UPC: 700702800921 |

Search - Johann Sebastian Bach, Gwendolyn Toth :: Bach: Goldberg Variations

| Johann Sebastian Bach, Gwendolyn Toth Bach: Goldberg Variations Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsA performance such as Bach intended. John J. Collins | Raritan, NJ, USA | 01/23/2004 (5 out of 5 stars) "From the very opening notes of this recording I realized I had made a good selection. I have other recordings of the Goldberg Variations, but this is the one I now like best. Recorded using a lautenwerk, or gut-stringed harpsichord -- an instrument much admired by Bach (it is known that he owned two and his cousin, Johann Nicholaus Bach was a lautenwerk maker) -- I believe this is how Bach himself would have liked this work to have sounded. Bach was very fond of this instrument (as well as the clavichord). The lautenwerk is a much more intimate-sounding instrument than the metal-stringed harpsichord and sounds like a lute. Gwendolyn Toth gives a most elegant performance here. Dr. Toth is the founder/conductor of the New York based ARTEK Ensemble, an early music group that performs using period instruments. Her interpretation of the Goldberg Variations is even throughout and avoids the bombastic interpretations sometimes heard on earlier harpsichord recordings or those using a piano. I found her performance charming and joyful and a breath of fresh air for Bach's music. I hope she will consider further recordings using this instrument." The Parallel Universe of String Theory Giordano Bruno | Wherever I am, I am. | 06/13/2010 (5 out of 5 stars) "The instrument heard on this recording is a Lautenwerk - a "lute-works" - built by Willard Martin in 1988, based on descriptions and fragmentary sources rather than an replica of a period instrument. In fact, no intact Lautenwerken survived into the 20th C, even though the instrument was not uncommon in the lifetime of JS Bach. Thus we have no idea, really, how fine or foul an instrument Willard Martin's hypothetical Lautenwerk might be, in comparison to the two expensive Lautenwerken that were listed among Bach's six keyboards at the time of his death. "We" also have no notion of how differently Bach himself, or any other keyboardist, might have touched the instrument. There are sources that assert how much the Lautenwerk sounded like a lute, but I don't hear any such sound on this CD. It sounds like a keyboard instrument as surely as any harpsichord, clavichord, or fortepiano. Serious advocates for the clavichord in our times have indeed developed a distinctive "touch' for their instrument, but to my ears it sounds as if Gwendoleyn Toth plays the Lautenwerk with the developed technique of a harpsichordist. That is a limiting factor, I think, in the success of this performance; the harpsichord "touch" and thus the Lautenwerk sounds quite lovely on some of the 30 variations - #17 and #20 for instance - but distinctly odd on others.

So what was a Lautenwerk? The fundamental difference from the harpsichord was that the strings were gut, like lute strings, rather than metal wire. Bach's two Lautenwerken were catalogued as "without dampers", a construction that would have significant implications for the overall 'sound' of the instruments. Any string plucked or hammered will vibrate until its sound 'decays' unless damped or stopped deliberately. The 'decay' properties of gut strings are quite different from those of wire metal strings. Judging by this recording, the 'decay' of the longer gut strings is far slower than that of the shorter strings. Bach's own cousin Johann Nicolaus of Jena was a Lautenwerk builder, by the way, and most of the written sources of info about the instrument are replete with praise for its musical potential. Those sources include mention of the fact that such instruments were of double register, with a "4-foot" treble register using brass strings. The specs for Willard martin's reconstruction are interesting: it has a disposition of two 8-foot-pitch sets of gut strings with two plucking positions, plus a 4-foot brass register with a buff stop; two keyboard manuals with handstops; leather and quill plectra. It is tuned at a low chamber pitch of A=370, according to the 'ordinary' temperament of the early 18th C, in other words, "mean" rather than modern equal temperament. The low pitch and mean tuning, to my ears, have musical virtues in this performance, which you should be able to notice especially in variation 28; overall, the sound is gentler than that of most harpsichord or modern piano versions. But the contrasts that can be rendered by the double manuals and by the combination of the gut register in the left hand and the higher brass register in the right hand are marvelously effective. Gwendolyn Toth interprets the Goldberg Variations brightly and briskly, shunning any scent of emotional turmoil in them. In her interpretation, they are what Bach himself called them: Clavierübung, Keyboard Exercises, requiring extremely virtuosic fingering and expressing chiefly the 'mathematical' beauty of music in canon and counterpoint. Listeners who relish the histrionics of most modern pianist interpreters will almost surely scorn Ms. Toth's rendition. I wouldn't maintain that this performance is the equal of the recordings of the Goldbergs on harpsichord by Fabio Bonizzoni, Bob van Asperen, or Pieter-Jan Belder, but it's a richly interesting alternative. The few places where the Lautenwerk sounds awkward to me occur when the left-hand lower passages get muddy because of acoustic traffic congestion, the extended 'decay' of notes piling into each other. What the harpsichord offers in superiority to the modern piano - and to the Lautenwerk played here - is the utmost transparency that results from its quick decay. The modern grand piano, with its crossed registers of strings, even when rendered as 'dry' by pedal technique as Glenn Gould's performances, sounds unsatisfactory to my ears in exactly the same passages as the Lautenwerk -- too much jumbling of overtones and sympathetic resonances! Whether a more specific Lautenwerk-technique might clarify such passages, I can't really guess. It's probably a shame that the Lautenwerk fell by the wayside of musical history, but then the same could be said of many marvelous bowed strings and winds. It was too soft in timbre, too subject to the necessity of constant retuning, and too little dramatically percussive to compete with the evolving piano. Nevertheless, on this CD at least, "we" have the chance to hear and appreciate it, as if it had continued to thrive in a parallel universe, where the 'catastrophe' of the well-tempered scale was tried and rejected." |

Track Listings (16) - Disc #1

Track Listings (16) - Disc #1