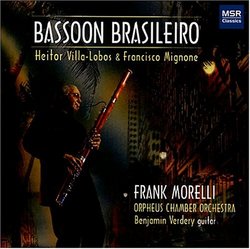

| All Artists: Villa-Lobos, Mignone, Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, Frank Morelli Title: Bassoon Brasileiro Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: MSR Classics Release Date: 8/24/2004 Genres: Dance & Electronic, Pop, Classical Styles: Vocal Pop, Opera & Classical Vocal, Chamber Music, Forms & Genres, Concertos, Historical Periods, Classical (c.1770-1830), Modern, 20th, & 21st Century, Instruments, Reeds & Winds Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 681585111024 |

Search - Villa-Lobos, Mignone, Orpheus Chamber Orchestra :: Bassoon Brasileiro

| Villa-Lobos, Mignone, Orpheus Chamber Orchestra Bassoon Brasileiro Genres: Dance & Electronic, Pop, Classical

The Rise of Brazil's Musical Identity The first decades of the twentieth century fostered an important transformation in Brazil. According to Heitor Villa-Lobos' biographer Simon Wright, there existed "an increasingly vol... more » |

Larger Image |

CD Details

Synopsis

Album Description

The Rise of Brazil's Musical Identity The first decades of the twentieth century fostered an important transformation in Brazil. According to Heitor Villa-Lobos' biographer Simon Wright, there existed "an increasingly volatile artistic climate...which saw to it that the old, monarchical snobbery surrounding serious music was broken down and destroyed by a movement flagrantly demanding change. Of this movement, Villa-Lobos became the vanguard." Villa-Lobos was born in Rio de Janeiro in 1887. Already playing guitar with the street musicians of Rio while in his teens, Villa-Lobos portrayed his music education this way: "My first book was the map of Brazil, the Brazil that I trudged, city by city, state by state, forest by forest, searching the soul of the land." These experiences would greatly influence the development of the foremost, authentically Brazilian composer outside the realm of popular music. Francisco Mignone, the son of newly arrived Italian immigrants, was born in São Paolo in 1897, a decade after Villa-Lobos, and like him, began performing popular music while in his teens. Although Mignone wrote numerous popular songs using a pseudonym, his study of composition in the European musical tradition in both Brazil and Europe led him to write "serious" music in the European style until the 1930's. While Mignone was studying in Europe, the "Week of Modern Art" of 1922 took place in São Paulo. Part of the celebration of the hundredth anniversary of Brazilian independence, the goal was to further the development of a Brazilian cultural identity. The Brazilian writer and ethnomusicologist, Mario de Andrade, underscored this new thinking: "The current historical criterion of Brazilian Music is that of a musical manifestation, which?reflects the musical characteristics of our race. Where are these characteristics? In popular music." Villa-Lobos was seen as the composer best representing the true Brazilian voice in modern music. Poet Ronald de Carvalho, proclaimed: "The music of Villa-Lobos is one of the most perfect expressions of our culture. In it quivers the flame of our race, what is most beautiful and original in the Brazilian race." After Mignone's return in 1929, he resumed his long friendship with Mario Andrade. Profoundly influenced by Andrade, Mignone came to embrace Brazilian nationalism. Although the form of his Concertino for Bassoon and Chamber Orchestra written in 1957 is traditional, the themes are clearly Brazilian in character. The first movement is a slow modinha or love song, and the rondo theme of the fast second movement is a carioca. Mignone wrote this showpiece for the virtuoso French bassoonist Noël Devos, who had immigrated to Rio in the 1950's. The Aria movement from Bachianas Brasileiras No. 5, written by Villa-Lobos in 1938, is also a modinha in the popular Brazilian style. Scored for soprano and ensemble of cellos, Villa-Lobos later adapted it for soprano and guitar. In the version heard here, the bassoon sings the soulful soprano line. In the original, the outer sections have no words and are sung as a vocalise. Only in the middle section are there verses, written in a declamatory style. The text, by Ruth Valadares Correa, describes a midnight scene: the moon "glorifying the evening like a beauteous maiden? while sky and earth, yea, nature with applause salute her?waking the soul and constraining hearts to cruel tears and bitter dejection." The Ciranda das Sete Notas (Round Dance of Seven Notes) for bassoon and strings, an original piece by Villa-Lobos written in 1933, was inspired by the ciranda, a children's round dance. Although Villa-Lobos often avoided using traditional forms found in European music, this piece is organized in four sections, played with little or no pause. The opening section, which should sound almost improvised, is followed by a scherzo complete with a haunting trio. An interlude reminiscent of the opening of Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring then leads

Track Listings (4) - Disc #1

Track Listings (4) - Disc #1