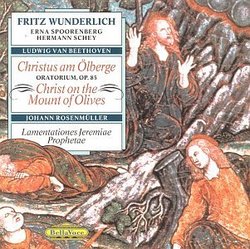

| All Artists: Ludwig van Beethoven, Johann Rosenmuller, Henk Spruit, Radio Philharmonic Orchestra, Hubert Giesen, Erna Spoorenberg, Fritz Wunderlich Title: Beethoven: Christus am Ölberge; Rosenmüller: Lamentationes Jeremiae Prophetae Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Bella Voce Records Release Date: 11/21/1995 Genres: Pop, Classical Styles: Vocal Pop, Opera & Classical Vocal, Historical Periods, Baroque (c.1600-1750), Classical (c.1770-1830) Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPCs: 789368281022, 8712177022533 |

Search - Ludwig van Beethoven, Johann Rosenmuller, Henk Spruit :: Beethoven: Christus am Ölberge; Rosenmüller: Lamentationes Jeremiae Prophetae

| Ludwig van Beethoven, Johann Rosenmuller, Henk Spruit Beethoven: Christus am Ölberge; Rosenmüller: Lamentationes Jeremiae Prophetae Genres: Pop, Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsWHAT AGONY IN THE GARDEN? DAVID BRYSON | Glossop Derbyshire England | 03/03/2009 (5 out of 5 stars) "This item is probably not easy to find. It may not be something you would have wanted anyway, but for what it may be worth bear with me while I explain briefly why it has been one of my own most interesting musical acquisitions in years. Beethoven's solitary 'oratorio' has not had a very good press. Marion Scott's Master Musicians book on this master musician generally assesses his works with a degree of reverence that would be hyperbolic if it were applied to all nine Muses on Mount Helicon. However when it comes to Christus am Oelberge (and also the triple concerto), Miss Scott seems to sense a need to right the balance and goes over the top with criticism that I feel to be unjust and misleading. The Seraph, I recall, is 'a high caricatura soprano', which is witty but unperceptive in my own view. Christus, to me, is a fascinating composition. It is not a success, but because Beethoven has not found a suitable style, not because it is bad music. Indeed in the course of fumbling for a suitable style Beethoven actually does some things that he never did again, and I wonder how many hear these features as I do. Another magnet for collectors must be that this disc preserves the art of the fine tenor Fritz Wunderlich, cut off in his prime after falling down some stairs at age 35, and also that of the soprano Erna Spoorenberg and the bass Hermann Schey who takes the small part of Peter. By way of added value and interest we have here also four of Beethoven's songs, including the great Adelaide, taken from a live recital that Wunderlich gave in 1966, the year of his death, plus three Lamentations of Jeremiah by Johann Rosenmueller (1619-1684) sung to a small cembalo and cello. It is all a long long way from the world of Complete Sets of the sonatas or symphonies, and frankly the further the better so far as I am concerned. Beethoven and assembly lines do not go. Such as Christus is, I think that the artists do the right things with it. In particular they don't try to disguise its stylistic uncertainty but take it at face value. Moreover the recording, from 1957, is not bad at all. The voices are a bit too near, but it was hard to find a recording at that period in which soloists were not recorded in too close a focus. The orchestral playing is good, the conductor is in sympathy with the music, and if there is any significant shortcoming it may relate to the way the chorus is reproduced. I say advisedly 'may' - Beethoven's choral idiom is nothing to write home about at any stage of his career. It all starts very well. The prelude is solemn and impressive, and I wonder whether it was echoing in Brahms's head at the start of the Alto Rhapsody. The following recitative and aria for Christ also make me think of Brahms, and more confidently. I would put a small wager on it that this music had a lot of influence on the long first solo in Brahms's great Rinaldo, and that is no mean compliment. However it highlights the problem in giving the part of Christ to a tenor. It is bound to sound rather operatic, and the operatic sense is magnified tenfold when the Seraph follows on. The style is just not appropriate, but nor does it deserve Miss Scott's witticisms. Certainly composers such as Handel or Verdi, more adept than Beethoven at opera, would have known better than to deploy this musical idiom in a sacred work. I suspect that Beethoven had in mind certain compositions by Mozart, e.g. Exsultate jubilate, but again Mozart was sensitive to the difference between what he could do in a short freestanding piece and what decorum calls for in a longer work. In fact the influence of Mozart is very strong, and I am in little doubt that I hear the statue from Don Giovanni here. However one thing keeps striking me as extraordinary - Mozart shares with Handel the distinction of being the most difficult of all the great composers to imitate, pastiche is not a gift that I would normally look for in Beethoven who in my view fell into a trap when he tried to mimic his revered Handel, but this is actually far and away the most successful pastiche-Mozart that I have ever heard. Wunderlich and Spoorenberg may or may not have taken this view, but they give the music full value for what it is, even when Wunderlich signs off Willkommen, Tod less like Mozart than like Manrico. Next is the fascinating Rosenmueller selection, three Latin Lamentations intriguingly numbered 2, 3 and then another 3. Here Wunderlich is far too close, so close that I could not make out whether the 'cembalo' is a harpsichord or, as I think, some kind of fortepiano. Nevertheless a very interesting oddity indeed. Last we have the four songs, from 1966 and much more realistically balanced. These are beautifully done, especially in Adelaide, sung in a heavenly cantabile. The accompanist is not such a polished performer as the likes of Roger Vignoles, Graham Johnson or Malcolm Martineau, but he is warm and gemuetlich and I like his work. That's it, folks. If it interests you and you can find a copy, you don't need me to say be careful what you pay for it. I got it cheaply, but if it came to the bit I would sell a few Complete Sets to obtain it. As an ironic postscript, let me draw attention to a fascinating work of biblical scholarship, The Evolution of the Gospel by J Enoch Powell. To the outrage of many divines Powell says `The Agony in the Garden is transparent fiction.' As my own reservations concerned musical style in a sacred context, maybe we don't have to bother unduly after all on that score." An unusual and even rare compilation featuring the wonderful Ralph Moore | Bishop's Stortford, UK | 04/05/2009 (5 out of 5 stars) "Odd that even as I write you can pay the earth for this disc yet it is also available on Amazon.uk Marketplace for a few pounds. There are lots of reasons for acquiring it - but not too expensively - not least, to hear Fritz Wunderlich in finest voice, reminding us what was lost when he died nine days before his thirty-sixth birthday: one of the most headily beautiful lyric tenors ever. His was not a large voice but he was so musical and refined without ever sounding like one of those throaty, constricted British tenors I shall not mention; his was a very virile and forthright sound nonetheless capable of great nuance and sweetness. Everything here shows off his voice to advantage, but I particularly like the Beethoven songs; his "Adelaide" challenges the peerless Björling version and the Rosenmüller excerpt is a Baroque rarity.

The sound is really very good for a live 1957 recording; there is some print-through and harshness but the solo voices in particular are very clear. It might be an early work, and the thirty-two-year-old composer is evidently not entirely confortable with the idiom, but some passages, such as the stately, pacing introduction, are already vintage Beethoven. It is already more of an opera than an oratorio, and thus, despite the obvious influence of Mozart, the recitatives and choral passages are often proleptic of "Fidelio"; there is a typical directness and honesty of expression so typical of Beethoven. The other two singers also provide pleasure. Spoorenberg has a clear, sappy, vibrant tone and Hermann Schey, although obviously already mature of voice and well advanced into his long career, knows what he is doing, despite the slightly laboured vibrato. The Terzett (Band 6) is especially lovely. The orchestra and chorus are somewhat recessed compared with the prominence of the solo voices but the latter are what you really want to hear in any case. I am not bothered by the incongruities of style here when it is performed with such conviction and artistry, and though it would be idle to claim that this is a neglected masterwork, it is certainly worth acquiring given its appeal on several different fronts." |

Track Listings (11) - Disc #1

Track Listings (11) - Disc #1