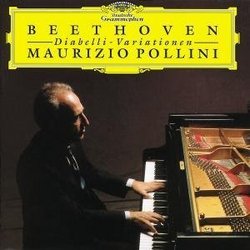

| All Artists: Ludwig van Beethoven, Maurizio Pollini Title: Beethoven: Diabelli Variations Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Deutsche Grammophon Release Date: 9/12/2000 Genre: Classical Styles: Chamber Music, Historical Periods, Classical (c.1770-1830) Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 028945964522 |

Search - Ludwig van Beethoven, Maurizio Pollini :: Beethoven: Diabelli Variations

| Ludwig van Beethoven, Maurizio Pollini Beethoven: Diabelli Variations Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsBeethoven steals the show Juan Carlos Garelli | Buenos Aires, City of Buenos Aires, Argentina | 09/29/2001 (5 out of 5 stars) "Pollini's greatest achievement in this recording is to let Beethoven flow in all its complexity to show us how deeply he has studied this masterpiece and how it was concocted: In 1819, the Viennese music publisher Anton Diabelli circulated a waltz of his own invention to 50 composers, each of whom was requested to contribute a variation to the collective project. Beethoven at first disdained the theme as a "cobbler's patch" on account of its mechanical sequences, and then overreacted to Diabelli's invitation, conceiving not one, but 23 variations, 10 fewer than the final number. Recent study of Beethoven's musical manuscripts from 1819 has cast a revealing light on the structure and import of this great work, his longest and one of his most cognitively and emotionally demanding pieces for piano. After having set the composition aside for several years, Beethoven expanded his draft from within in 1823, adding variations 1-2, 15, 23-26, 28-29, and 31 to the pre-established order, while greatly elaborating on the conclusion. No other work by Beethoven is so rich in allusion, humour, and parody. Trivial or repetitious features of the waltz, such as the C major chords repeated ten-fold in the right hand in the opening bars, can be mercilessly exaggerated, as in variation 21, or dissolved into silence, as in variation 13. Inconspicuous elements of the theme, such as the ornamental turn heard at the outset, can assume astonishing importance, as in variations 9 and 11, which are based throughout on the turn. Several variations allude to Mozart, Bach, and other composers. The most obvious of these is the reference, in the unison octaves of variation 22, to "Notte e giorno faticar" from the beginning of Mozart's Don Giovanni. This allusion is brilliant not only through the musical affinity of the themes -which share, e.g., the same descending fourth and fifth- but through the reference to Mozart's Leporello. Beethoven's relationship to his theme, like Leporello's relationship to his master, is critical but faithful. And like Leporello, the variations after this point gain the capacity for disguise. Variation 23 is an étude-like parody of pianistic virtuosity alluding to the Pianoforte-Method by J.B.Cramer, whereas variation 24, the Fughetta, shows an affinity in its intensely sublimated atmosphere to some organ pieces from the third part of the Clavierübung by Bach. The work as a whole consists of one large form with three distinct regions. The opening variations remain close to basic parameters of the theme (such as its metre) and show gradually increasing freeedom, which at last turns into dissociation in the contrasting canonic variations Nos. 19 and 20, and in No. 21, in which the structural parts of each variation half are themselves placed into opposition. In performance time, these variations represent the midpoint. A sense of larger formal coherence is created through unusually direct reference to the melodic shape of the original waltz in three variations inserted in 1823 -Nos. 1, 15, and 25. In No. 25 the waltz is reincarnated as a humorous German dance, but this image is gradually obliterated in the interconnected series of fast variations culminating in No. 28, in which harsh dissonances dominate every strong beat throughout. After Variation 28, we enter a transfigured realm, in which Diabelli's waltz, and the world it represents, seem to be left behind. A group of three slow variations in the minor culminates in Variation 31, an elaborate aria reminiscent of the decorated minor variation of Bach's Goldberg set, while also foreshadowing the style of Chopin. The energetic fugue on E flat that follows is initially Handelian in character; its second part builds to a tremendous climax with three subjects combined simultaneously before the fugue dissipates into a powerful dissonant chord. An impressive transition leads to C major, and to the final and most subtle variation of all: a Mozartian minuet whose working-through through rhythmic means leads, in the coda, to an ethereal texture, strongly reminiscent of the famous Arietta movement of Beethoven's own last sonata, Op 111, composed in 1822. Herein lies the final surprise: the Arietta movement, itself influenced by the Diabelli project, became in turn Beethoven's model for the last of the Diabelli Variations. The end of the series of allusions thus became a self-reference and final point of orientation within an artwork whose vast scope ranges from the ironic caricature to sublime transformation of the commonplace waltz." Remarkable Bruce J Murray | Tuscaloosa, AL USA | 12/28/2000 (5 out of 5 stars) "Pollini was rumored to have a Diabelli recording in the making as far back as 1980. A better match for performer and work can hardly be imagined. The disc joins the short list of great Diabellis on record (Schnabel, Shure, Serkins father and son).The performance is not quite what many would expect from the pianist. There is a quality of rumination that Pollini in 1980 might not have achieved. The architecture of the work (or an architecture, at least) is revealed with a confidence that rivals Schnabel's. The final variation is taken at a stunningly slow tempo; I was reminded of the Vegh Quartet playing the slow movement of Op. 135.The Diabelli is one of the greatest challenges for the pianist-musician. Pollini has risen to the task. The disc commands attention and respect." Pollini's Diabelli Variations: a testament? Patrick Pierre-Louis | Delmas, Haiti | 03/20/2001 (5 out of 5 stars) "I always thought that Beethoven's Diabelli Variations were the piece that suited best Pollini's art and hoped that someday he would decide to record them. But, as ready as I have been, Pollini's interpretation has spoiled all my expectations. Surely, his Diabelli have the same stature with the definitive version of the last Beethoven piano sonatas he signed with Deuschte Gramophon but they are not in the same vein. Here we find a more moving interpreter, vulnerable and almost fragile in expression. Listen to Variations 7, 8, 11, 13, the hesitant lightness of the basses sounding like a kind of barcarole. Variation 20 is played with supreme abandon as an agonizing heartbeat while variation 24 (fughetta) made one regret even more that Pollini has not recorded Bach's Well tempered Klavier. As to Variations 31 and 33, they sound profoundly dramatic by means of sheer reserve and projection in the unknown. Could one expect to listen to a more interrogative version? Polllini plays those variations as if he had no straight answer and kept wondering and wandering about aimlessly expressing thus surprising humility in his approach of this masterpiece.I have several versions of Diabelli Variations respectively by Pludermacher, Brendel (DG, Vox), Kovacevich, Arrau and above all Richter. Yet, Pollini is second to none. Apparently less authoritative than Richter, he is at the same time more human.Pollini has provided a stunning answer for those who still doubted his capacity to show pure sensitivity."

|

Track Listings (34) - Disc #1

Track Listings (34) - Disc #1