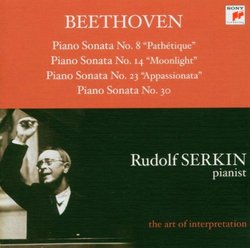

| All Artists: Ludwig van Beethoven, Rudolf Serkin Title: Beethoven: Piano Sonatas Nos 8, 14, 23, 30 Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Sony Bmg Europe Original Release Date: 1/1/2003 Re-Release Date: 9/1/2003 Album Type: Import, Original recording remastered Genre: Classical Styles: Chamber Music, Forms & Genres, Sonatas, Historical Periods, Classical (c.1770-1830), Romantic (c.1820-1910) Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 |

Search - Ludwig van Beethoven, Rudolf Serkin :: Beethoven: Piano Sonatas Nos 8, 14, 23, 30

| Ludwig van Beethoven, Rudolf Serkin Beethoven: Piano Sonatas Nos 8, 14, 23, 30 Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsWHAT BEETHOVEN IS ALL ABOUT DAVID BRYSON | Glossop Derbyshire England | 03/26/2004 (4 out of 5 stars) "I should imagine that the admirers of this great player will be swooping on this reissue. The four performances here date from the period 1941 to 1952 when he was at the absolute peak of his powers. He did a post-war disc of the Appassionata, Pathetique and `Moonlight', but the only other op 109 that I know of from him is included in the posthumous set, issued by Peter Serkin, of performances that he himself had originally refused to release. In addition there is an Appassionata in his 1957 Lugano recital, plus at least one other on a disc of a live performance available in Canada. The recorded quality here does not permit a 5-star rating in the year 2004, but it is not bad at all and presumably will not deter those grateful to get anything they can from this greatest of Beethoven-players. The Pathetique is very like his post-war recording only more so, to use an awkward expression. The outer movements are lithe and athletic, the first movement is even a tad faster here, and as always he includes the opening Grave in the repeat. Where I distinctly prefer this account is in the slow movement where there is much more warmth than in his slightly solemn later reading. In op 27/2 it is an intense pleasure to come back to Serkin after listening to certain other accounts. I have a deep and rooted dislike of genteel and prettified playing in the first movement such as I am served up by Ashkenazy and Lupu, not so much moonlight as moonshine. Serkin takes it very slowly and with very little overt rubato, and even in a 1941 recording I can still detect his special way of keeping the sound resonating in the left-hand octaves - he used to pump the keys silently. The middle movement is much as he always did it - slowish, very stylised and with a kind of `curtseying' feel about the rhythm in the outer sections, and a strong and emphatic tone in the left hand in the trio. The last movement is even better than in the post-war issue. I have heard it played as fast as Serkin does it, but never as well. There is absolutely no pedal in the rising arpeggios, and this time there is not even the minutest hint of a hesitation as he repositions his hand from above the treble to deep in the bass. This particular trick was a favourite of Richter's, and in passing it has always interested me that Michelangeli, probably the greatest keyboard technician there has ever been, seemed to scorn the effect. Where the right hand had to change its locus in such an abrupt way Michelangeli, far from seeking seamless continuity, used typically to make a great gulping hiatus. Where the 1941 recording can't equal the later one is in the great chomping chords near the end of the exposition and recapitulation. Serkin `orchestrated' these in a quite extraordinary way that the early recording doesn't capture, but one can't have everything. There are now three Appassionatas from him in my collection, and in terms purely of the performances there is very little indeed to choose. My favourite by a very small margin is probably still in his 1957 live Lugano record, despite a couple of wrong notes at the height of the fury in the middle of the first movement. Where that scores is in a completely outstanding performance of the andante plus the way he delivers the theme of the finale in a sinister mezza voce. I still miss the way he seemed near to splintering the keyboard in the post-war record during the fortissimo chords immediately after the start, and even a very curious touch at the end of the first phrase in the sonata. On the post-war record there is a curious twang on the last note. I had always taken this as a pressing fault until one day I heard him live, and there, not 3 metres from me, he produced exactly the same effect. Goodness knows how it was done, much less what he meant by it. The finale, of course, is taken at the speed Beethoven was very careful to indicate, although interestingly Serkin does the transition a bit faster this time before slowing down to his normal tempo. The op 109 is distinctly preferable to the posthumous account, the first movement rather livelier and with less pedal, and the prestissimo more as I envisage that tempo. The final andante with variations is awesomely grave and beautiful, although I still wonder whether the main speed is really `andante'. It would definitely be slow for the middle movement of the 5th piano concerto, marked `adagio un poco mosso'. As the variations unfolded I soon stopped worrying about that.Beethoven lovers - miss this one if you want. I didn't." Diamantine performances! Hiram Gomez Pardo | Valencia, Venezuela | 03/21/2005 (5 out of 5 stars) "

In those years Serkin was in the peak of his powers; evidently his meetings with Adolf Busch and eventually his periodic encounters in Prades made him grow up to unexpected levels. Casals could call any musician he wanted, he was a supreme musical authority in the world, I presume this fact is a relevant proof about the intense musicianship and tonal splendor in the early thirties reached major levels. His encounter with Busch quartet kept the European approach and then Prades and specifically his works with Casals performing Beethoven's cello sonatas elevated him to cosmic heights. Precisely these seven years were extremely creative. His Waldstein's performance is among the top, the Sonata 30 is very interesting and so the Patetique is superb too. With the Appassionata I rather prefer his version of 1957 in Lugano. It' s important to remark his invaluable collaboration with Budapest's string quartet . His reading of the Piano quintet Op. 34 is absolutely definitive and his Diabelli variations are among the best in the market. So consider this album as a real must to acquire all the way. If you want to have in your collection a golden album, go for this historical recordings. " |

Track Listings (12) - Disc #1

Track Listings (12) - Disc #1