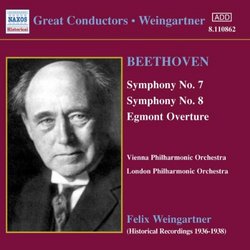

| All Artists: Ludwig van Beethoven, Felix Weingartner, London Philharmonic Orchestra, Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Title: Beethoven: Symphonies Nos. 7 & 8; Egmont Overture Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Naxos Original Release Date: 1/1/1936 Re-Release Date: 5/20/2003 Genre: Classical Styles: Historical Periods, Classical (c.1770-1830), Modern, 20th, & 21st Century, Symphonies Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPCs: 636943186220, 063694318622 |

Search - Ludwig van Beethoven, Felix Weingartner, London Philharmonic Orchestra :: Beethoven: Symphonies Nos. 7 & 8; Egmont Overture

| Ludwig van Beethoven, Felix Weingartner, London Philharmonic Orchestra Beethoven: Symphonies Nos. 7 & 8; Egmont Overture Genre: Classical |

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsSuperior Performances In Problematic Transfers Jeffrey Lipscomb | Sacramento, CA United States | 07/10/2004 (4 out of 5 stars) "To my ears, the Naxos series of Weingartner's historic Beethoven recordings has been something of a mixed bag (see my reviews of other entries in this series). Obert-Thorn's transfers of Weingartner's London-based recordings, Symphonies 2 and 4-6, strike me as the best we are ever likely to have. But the Vienna Phil. readings of 1, 3, and 7-9 have been taken from bass-deficient American Columbia 78s, and they have been subjected to various degrees of noise suppression. By contrast, the Opus Kura CD label (Japan) has taken a minimalist, undoctored approach using far fuller-sounding and more lifelike Japanese 78s (the original recordings of 7-9 were made by Nipponophone, a Japanese subsidiary of EMI). The result? Opus Kura has given us transfers of remarkable presence and immediacy that are simply astonishing in their sonic realism.To make matters more difficult for the prospective purchaser, these superior Japanese transfers are coupled differently than the Naxos issues. Opus Kura 2038 has #1 and #7, whereas Naxos has #1 paired with its superb #2, and Naxos' #7 is coupled on this disc under review with #8. Opus Kura 2039 has #3 paired with #8 (while Naxos has #3 coupled with its excellent #4). Finally, Opus Kura 2040 has put Weingartner's legendary #9 with the Creatures of Prometheus Overture (the latter in a different take than the one used by Naxos). The Naxos 9th has as filler its magnificent Consecration of the House Overture.The Opus Kura CDs cost fully twice as much as the Naxos issues, and I suppose you could call it yet another example of the old law of diminishing returns: the transfers are about 50% better and the cost is 100% higher! I have to say that I was quite happy with the Naxos transfers until I heard the fuller-sounding Opus Kura issues - so the choice is yours. The Opus Kura issues come "warts and all" and have much higher hiss and surface noise. And the 78 sides each have a different character (some of them, however, are so good that they are the aural equivalent of the sun coming out from behind the clouds). Also, the side joins are not as smoothly handled as they are on Naxos: some have a slight pause, while others have a mild deviation in pitch (I don't have perfect pitch, but that might bother some of you who do).So much has already been written about the special qualities of these Weingartner performances that I feel there is little for me to add. This 7th belies the conductor's reputation as a straight and literal interpreter - there are numerous subtle tempo fluctuations that, to my ears, really give this reading a quality of organic growth. The slow mvt. is very expressive, and the Scherzo has wonderful energy (despite a rather slowish Trio). The finale is a marvelous excercise in gradual acceleration. I think the Opus Kura may be using a different 78 side (an alternate take) for the opening of the 1st mvt. that is more persuasively grand and rhetorical. If I sound rather equivocal, it's because the sound is so much fuller and three dimensional than on the Naxos that I can't be absolutely certain.Weingartner's 8th is extremely good-natured and moderate in tempo. Its speed is midway between two extremes: the breathtakingly uptempo (and exciting!) Scherchen/Royal Phil (EMI) and the VERY stately Knappertsbusch/Munich (Ermitage). The reverberance of the old Grosser Musikvereinsaal is more noticeable here. One blemish, to my mind, is the slightly unsteady start to the Allegretto scherzando - perhaps it was Weingartner's way of adding to Beethoven's jibe at Maelzel's infamous metronome. Here and there are a few other minor imprecisions in the VPO's playing, but none of them diminish Weingartner's genial mixture of drama and warmth.I am almost embarrassed to admit to owning 25 recordings of the 7th and 15 of the 8th. Some are involuntary: I only own the pedantic Ferencsik/Chicago and ponderous Fricsay/BPO 7ths because they are part of large, multi-disc sets. Several are on old LPs that I keep for reference: the 1927 Stowkowski/Phil. (with its perfumed slow mvt. and ridiculously exaggerated portamenti in the finale), the 1936 Toscanini/NY Phil. (which now repels me with its excessive tension and clipped phrasings), and the mono Klemperer/Philharmonia which, like both Erich and Carlos Kleiber, opts for pizzicato instead of arco strings in the last measure of the 2nd mvt. The most perfect realization of the 7th I have ever heard is the 1930's Rudolf Schulz-Dornburg Berlin Radio recording (CDC 880455, coupled with a massively thunderous and rhytmically unsteady Bruno Walter/NY Phil 8th). If you are curious to hear it, there are copies available at Berkshire Record Outlet (broinc.com) for only $5. Scherchen's 8th leaves me grinning from ear to ear every time I hear it; there is also a very fine Rosbaud 8th on Hanssler. But make no mistake: these wonderful Weingartner readings of 7 & 8 will also get loaded when I depart for the proverbial desert island." The Notable Weingartner Beethoven Series Continues J Scott Morrison | Middlebury VT, USA | 05/20/2003 (5 out of 5 stars) "A younger friend, otherwise fairly knowledgable about classical music, asked me who Felix Weingartner was. I was surprised that he didn't know of him, and it was then that I realized what a special service Naxos is doing by releasing this series of Beethoven recordings by a man I tend to think of as one of the first 'modern' conductors. I've raved previously about the Third, Fifth and Sixth Symphony releases, and here's another one that is a winner. The Seventh and Eighth Symphonies, with Weingartner conducting the Vienna Philharmonic, are included here, as well as the familiar Egmont Overture plus two short excerpts from Beethoven's other incidental music for Goethe's play. I had a music professor who always referred to the Seventh and Eighth Symphonies as 'the sunny ones,' and he was right. Although the Seventh is heroic in scope, it is unfailingly sunny in outlook and Wagner nailed it when he called the final movement 'the apotheosis of the dance.' The Eighth, which was written immediately after the Seventh, is in the same optimistic vein, although it is a slenderer (and perhaps more humorous) work. Weingartner apparently saw this connection, too, because he programmed the two together at times. These recordings, from the 1930s, were famous in their day and should be well-known now as well. They would be, I suspect, if they were in modern sound. Weingartner's approach is fairly straightforward, but with subtle management of tempi and phrasing; there are no longueurs, no pushing and pulling tempi as some of his contemporaries did. The only obvious place where he departs slightly from Beethoven's markings (and it's really a matter of choice, I think) is the tempo of the trio and its repeat in the Scherzo of the Seventh; Weingartner takes it quite slowly. It is notable that uncharacteristically he makes the changes of tempo within the movement abruptly, so obviously it was his intention, not some oversight on his part. Throughout both symphonies one is aware of the singing line and the underlying dance rhythms. I suspect that is precisely what Beethoven had in mind. I have always valued both of these performances and am glad to have them in the refurbished sound provided by Mark Obert-Thorn, one of our best transfer engineers. They are not, as I've said, in modern sound, but for recordings of their era they are exemplary. Many thanks to Naxos for bringing these exceptional performances back to us in good sound and at budget prices.You probably already own performances of these pieces in modern sound, but you also might want to give this issue a listen, too, because Weingartner has something genuine to say about them and the price certainly won't raid your wallet.Scott Morrison" Great Beethoven Conducting and Playing Ralph J. Steinberg | New York, NY United States | 07/23/2003 (5 out of 5 stars) "Weingartner's Beethoven Seventh was recorded the same year as Toscanini's Philharmonic account. No greater contrast can be imagined than between these two recordings. Weingartner succeeds where Toscanini fails, in giving the Symphony a buoyancy and grace that is completely destroyed by the Italian's characteristic metronomic haste. One very "individualistic" touch occurs in the First Movement Coda: Weingartner broadens the tempo at the very beginning of the Coda, applies quite massive rubati to the bass figurations, and holds to this slower tempo to the very end of the movement. By contrast, the Finale is a gradual and steady accellerando until the Coda is played with overwhelming Dionysian fury. The Eighth Symphony and "Egmont" Overture are likewise treated to supple and sensible tempo fluctuations which truly animate this "Vortrag." As in the Ninth Symphony, Weingartner shows himself to be a master of the Beethoven style, giving the music room to breathe, as well as maintain the structure of the work. The transfers are really superb. I love all the Naxos Weingarter reissues, but I must admit that the Vienna Philharmonic Beethoven series is especially precious to me. MORE WEINGARTNER, PLEASE!!!! BUT THE OPUS KURA IS EVEN BETTER!"

|