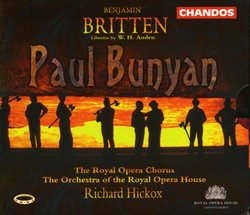

| All Artists: Benjamin Britten, Richard Hickox, Peter Coleman-Wright, Kenneth Cranham, Timothy Robinson, Kurt Streit, Roderick Earle, Pamela Helen Stephen, Susan Gritton, Lilian Watson Title: Britten: Paul Bunyan / Coleman-Wright, Cranham, Streit, Gritton, Robinson, Watosn; Hickox Members Wishing: 1 Total Copies: 0 Label: Chandos Release Date: 1/11/2000 Genre: Classical Style: Opera & Classical Vocal Number of Discs: 2 SwapaCD Credits: 2 UPC: 095115978122 |

Search - Benjamin Britten, Richard Hickox, Peter Coleman-Wright :: Britten: Paul Bunyan / Coleman-Wright, Cranham, Streit, Gritton, Robinson, Watosn; Hickox

| Benjamin Britten, Richard Hickox, Peter Coleman-Wright Britten: Paul Bunyan / Coleman-Wright, Cranham, Streit, Gritton, Robinson, Watosn; Hickox Genre: Classical |

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsBritten's virtually lost American masterpiece. darragh o'donoghue | 03/27/2002 (4 out of 5 stars) "There was much concern in the early decades of the 20th century with the creation of a genuinely American opera, a national music drama that would fuse native forms with the operatic modes laid down in Europe. The most celebrateed effort is Gershwin's 'Porgy And Bess'. But in Europe, composers were writing 'American' operas too, most notably Puccini and his 'The Golden Girl Of The West'. In the 30s and 40s, two European composer-writer teams offered their own sarrdonic spin on this sub-genre - Brecht/Weill with 'The Fall And Rise Of Mahogony', and Britten/Auden with 'Paul Bunyan' (written while the partnership were living in the States). Although both pairings could hardly be more different, there are striking similarities between the two operas, written within a decade of each other. Both are ironic epics dealing with a mythic America, a kind of rise-and-fall narrative relating or predicting progress and decline. Both make rich use of popular American music, in particular African-American forms such as jazz, blues and spirituals, but also ballads and country - this gives the individual numbers in 'Bunyan' a melodic immediacy not always associated with Britten. There are even songs in the opera that echo Weill, repeating that magic trick of brittle, mocking melancholy (e.g. 'Cooks' Duet', 'The Blue - Quartet Of The Defeated). Britten shares with the German a sustained use of musical parody (especially Wagner and sacred music) and bathos; an important place for the Chorus; the odd jerky march rhythm; and a preponderance of wind and brass. Auden even paraphrases some of Brecht's 'Threepenny Opera'-era ideas, especially in the figure of Johnny Inkslinger, the cultured idealist forced into capitalism by economic necessity - 'But I guess a guy gotta eat' (Auden's companion, Christopher Isherwood, famously translated Brecht's songs).'Paul Bunyan' plays like a modern Genesis/creationist story, opening, from nothing, with a talking forest, undisturbed lands waiting for the expansionist adventures of the pioneers. Bunyan engendered by supernatural agency, arrives in this Eden, flagged by pastoral flutes, and sets up a logging company. The first act deals with the recruitment of workers; the second with their unrest and desire to settle down or move on - a potted history of America (wilderness; European pioneers, agriculture, industry, politics, Hollywood - no Civil War or Indians, of course). This narrative, which equates America with the first Garden, the pioneer with a God-approved prophet and capitalism with Mainfest Destiny, is interrupted with flashforwards to future misery, and framed by a balladeer who narrates Paul's unlikely adventures in tall-tale shorthand. Paul, who significantly speaks his part throughout, is at once pioneer, secular 'father'/preacher/guide/Christ figure, genie, spirit of America, Cassandra, American dream, capitalist boss (tough but fair) - when asked, he defines himself: 'I am the Eternal Guest/I am Way/I am Act'.The hybridity of forms (including an exquisite, fugal duet and exotic proto-Bernstein rhythms; Britten called the film a 'choral operetta'), styles, ideas and tones evoke a multi-cultural melting pot that seems to be progressing towards some great End Of History; but the repetitions in the score and of individual scenes undercut this movement.The ensemble cast in this recording of the revised opera (1975) are remarkable, submitting to the wry complexities of Auden's mercurial libretto, at once comic, earnest, ironic, satiric, romantic. The Orchestra of the Royal Opera House emphasise the restless playfulness of the young Britten, as he veers from slapstick comedy to Blitzstein-like New Deal pageant to anachronistic Cole Porterisms to dark, tense drama. My only complaint refers to the major flaw of all Chandos recordings, the low sound mix, which makes it difficult at times to make out Auden's clear, clever words."

|