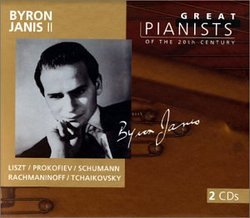

Amazon.comThe gold-fingered Byron Janis is often mentioned in the same context as the other young American lions in an era of cold war cultural competition, Van Cliburn and William Kapell. This anthology gives you a good sense of what it was that made Janis in particular so exciting during his vintage years in the early '60s (before the arthritis that derailed his career had struck, and from which he has attempted a recent comeback). Janis had a voracious appetite for taking risks, perhaps a part of the legacy of his one-on-one study with Vladimir Horowitz--but it's a kind of risk taking that is all his own and makes the concertos performed under Kiril Kondrashin (from a famous Moscow concert in 1962) pulse with discovery and excitement. He tears fearlessly into the "martial" finale of the Liszt Concerto No. 1 but also contributes buoyant high spirits. Against much subsequent competition, this account of Prokofiev's Third Piano Concerto--a piece used in the Richard Dreyfuss film The Competition--still amazes for its unerring sense of direction that still finds room for the composer's contradictory moods. Instead of reducing to acidic attitude and motoric machismo, Janis (obviously inspired by the white-hot input from the Moscow Philharmonic and Kondrashin) offers a wealth of textures and colorings, as well as much warmth. A more unabashedly romantic artist is at work in the First Piano Concerto of Rachmaninoff, which gets a dusting off and is presented with passionate conviction--wonderfully complementing Janis's rich account of the more-familiar Second Piano Concerto (listen to how much he packs into his build of the opening parade of sustained chords), where you shouldn't let yourself be off put by some of the strings' frayed intonation. Solo pieces here are a mesmerizing, knock-out early Prokofiev Toccata and a deeply personal bit from a Schumann rarity (the variations from the Piano Sonata No. 3, known as "concerto without orchestra"), which is maddeningly ripped from its context and leaves you aching to hear the work entire. --Thomas May

Track Listings (10) - Disc #1

Track Listings (10) - Disc #1