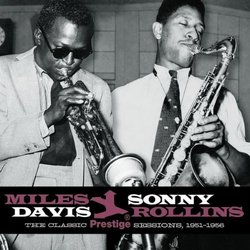

| All Artists: Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins Title: Classic Prestige Sessions 1951-1956 (Bril) Members Wishing: 3 Total Copies: 0 Label: Prestige Original Release Date: 1/1/2009 Re-Release Date: 8/4/2009 Genres: Jazz, Pop Styles: Cool Jazz, Bebop Number of Discs: 2 SwapaCD Credits: 2 UPCs: 888072314610, 0888072314610 |

Search - Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins :: Classic Prestige Sessions 1951-1956 (Bril)

| Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins Classic Prestige Sessions 1951-1956 (Bril) Genres: Jazz, Pop

In the early 1950's Miles Davis and Sonny Rollins developed a friendship and working relationship that produced some of the best and most important jazz of the decade. To prove the point, Prestige Records proudly presents ... more » |

Larger Image |

CD DetailsSynopsis

Album Description In the early 1950's Miles Davis and Sonny Rollins developed a friendship and working relationship that produced some of the best and most important jazz of the decade. To prove the point, Prestige Records proudly presents this all-new compilation that showcases just some of their stellar work together that was recorded for the famed jazz label. Similarly Requested CDs

|

CD ReviewsHARD BOP'S BABY PICTURES Mark E. Farrington | East Syracuse, NY | 08/16/2009 (4 out of 5 stars) "This set assembles all the Prestige tracks recorded by Miles Davis & Sonny Rollins, over 5 sessions, from January 1951 to March 1956. While Joe Tarantino's 24-bit transfers are excellent, the 1953-56 sessions (disc 2 of this collection) are available in better sound in the Van Gelder Remastered editions of COLLECTORS' ITEMS and BAG'S GROOVE (i.e., newly tranferred to 24-bit digital sound by the original engineer, Rudy Van Gelder). For this reason, my review concentrates on the two 1951 sessions (all of disc 1).

In 1951, Miles Davis was grappling with two life-sized challenges: one personal, one musical. First, as we all know, in the 1940s and early 50s heroin addiction was epidemic in the jazz community. By early 1951, Miles was at least one year into his habit - and by now "getting high" was hardly the object of "using" as much as it was to avoid feeling sick. He made sporadic attempts to kick his habit but, as he admits in his Autobiography, in 1951 he still wasn't ready to face it no-holds-barred. (In November 1953, he would do so.) Musically, in the immediate wake of the "Birth of the Cool" music of 1949-50 (including the exquisite Columbia sides with Sarah Vaughan), Miles found himself in the challenging position of having to "triangulate" a new music from mid-to-late 1940s BeBop on the one hand, and "Birth Of the Cool" on the other. Because he lacked the virtuosity demadned by BeBop, and needed a "working" situation minus the expense of the multiple arranged horns of "Cool," he had to cut a path to a newer aesthetic in which he could better reach his inner, stylistic Center. This would also involve working around (and, to a certain extent, overcoming) his technical limitations as a trumpet player. What all this comes down to, in terms of his early 50s recordings, is that Miles would have good days and bad days...The pa-thetic "Ezz-thetic" date of March 1951; the venomous "Serpent's Tooth" session of January 1953 with Bird and Sonny Rollins, despite a decent-enough version of "Round Midnight"; the not-so-tasty "Tasty Pudding" date of February 1953: these were some of the bad days. (The latter reminds me of Sir Winston Churchill's reaction to a particularly lackluster dessert : "This pudding...has no THEME.") However, what you will NOT hear, on any of these 1951 tracks, is the kind of strung-out, mental / emotional breakdown manifested on Charlie Parker's notorious 1946 "Lover Man" and "Max is Making Wax." (So sorry, jazz voyeurs, to ruin your day.) JANUARY 17, 1951 was a busy day for Miles. In the afternoon, for Norman Granz, he recorded his last truly fruitful session with Charlie Parker. (The "Star Eyes" from this date is, to say the least, a thing of beauty.) A few hours later Miles cut his first sides, as a leader, for Prestige. With him were Sonny Rollins, Benny Green, John Lewis, Percy Heath and Roy Haynes. The sound quality is so-so, even for the time. With a whole Charlie Parker session just behind him, Miles is alert and full of ideas, but frankly - I speak as trumpet player, myself - his lip is shot; it is a challenge for him just to get through simple, low-to-mid-range lines without cracking notes. The first track, "Morpheus," is a John Lewis Blues, bracketed with a kind of abstract, Birth-of-the-Coolish head-arrangement. (Prestige's Ira Gitler gave the tune its title because it brought to mind the ancient god of dreams.) Miles spins two choruses of boppish lines and at least manages to avoid embarrassing himself. Next comes "Down," another Blues, but with a more straight-ahead, funky character (as in "get DOWN"). Miles puts in two choruses; his personable, pleasantly lyrical way with the Blues, first heard on the 1945 "Now's the Time" with Charlie Parker, has obviously grown into its next stage. As Ira Gitler notes, "his solo...felt as if he was talking to you, telling a story as it were." To me it is the least unsuccessful track of the session. Two takes of "Blue Room" follow. (The first is obviously taken from an originally unrealeased, worn acetate with added reverb.) On both takes Miles indulges himself with sweet, moody lines (punctured with some "clams") , and on the first take Sonny Rollins already shows the sensual, "fluffy" tone and lyricism that would render him instantly recognizable. Meanwhile, John Lewis holds it all together with his disciplined, neoclassic taste. "Whispering" is next, a medium-tempo romp which surges along well enough, without really creating a new mood or exploring anything about the original tune. Before the session ended, John Lewis had a gig to get to, and so Miles "comps" admirably on piano for "I Know," a Sonny Rollins solo over the chords of "Confirmation." Technically, this is Rollins' first side as a "leader." It ends abruptly enough to make one wish it had gone on for a few more choruses. OCTOBER 5, 1951 marked Mile's next session as a leader - and the first intended for "Microgroove" or 33 1/3 RPM LPs (even if they were only the 10-inch variety). So we get more choruses, more stretching out than on the usual bop records, and something better than 78-RPM sound quality. Sonny Rollins is back with Miles, and joining them is the 19-year-old Jackie McLean on alto sax, Walter Bishop, Jr. on piano, Tommy Potter on bass and Art Blakey on drums. Charlie Parker attended this session, sitting in the control booth and making the young Jackie McLean very nervous (per Miles' Autobiography). But in the end, Bird's presence proved to be an encouragement, not an inhibitor. The overall "Music" here is somewhat raw or even stylistically unformed, because Miles & Company - whether they knew it or not - were moving toward a more polished Hard Bop idiom which hadn't yet been defined. That is to say, this session is really a series of "Baby Pictures" of Hard Bop. This is particularly the case with drummer Art Blakey. By the time of his sessions with Miles of April 1953 and March 1954, he has artistically grown in leaps and bounds ; his force-of-nature drive, while not at all REDUCED, is submitted to a refinement in texture and taste which is only hinted at in this session. "Conception," that is, Miles' altered version of George Shearing's bop classic, starts off the session with everyone in good form. Miles' solo is far more fluent and sinewy than the tentative (some would say "lame") one in the 1950 Birth-of-the-Cool version of this piece (where it is titled "Deception"). Art Blakey puts in his most tasteful work of the session, opting for a more uninhibited approach on most of the other tracks. But already, Miles presages Hard Bop : projecting the more advanced, harmonic intrigue of BeBop, he injects it, even at this tempo, with a more thougthful (some would say "contemplative") lyricism. (Miles notes, in his Autobiography, that no less than Charles Mingus stopped by, and sat in on bass for this track.) "Out of the Blue" is a mid-tempo, Hard-Bop-precursing piece based on the chords of "Get Happy," its seemingly cut-off phrase endings adding to its character. Stylistically, it strikes me as the most assured track of the session. Miles contributes two of his best early 50s solos, and Sonny Rollins, in his, quotes Thelonious Monk's "Well, You Needn't" with such non-chalance that you almost have to smile. "Denial" is "headless" (i.e., minus arranged melody), a traversal of the chords of Charlie Parker's "Confirmation." Miles begins , adhering to a more purely Bebop style, followed by the others. Ira Gitler's liner notes do not confirm this, but I have always suspected that the loosey-goosey, jam-sessionish feel of this track derives from its last-minute inclusion due to the presence of Bird Himself in the control booth...A tribute? Still, in spite of their promising beginnings, none of the solos end up as particularly memorable or deep-cutting. "Bluing" is next. At the time, much was made of the fact that this mid-tempo, unprecedentedly extended Blues was recorded with an "eye" toward the new LP format : it clocks in at 9 minutes, 55 seconds. But quantitatively AND qualitatively, Miles would surpass it on April 29, 1954, with his immortal, post-cold-turkey "comeback" Blues : the 13-minute, 25-second "Walkin'". Miles takes two seperate solos, his mastery of Blues Narrative developing rapidly (compare it to "Down"); Rollins & McLean are hardly less effective. Art Blakey "misses" the ending, having to effect an abrupt, Cayote-just-run-off-the-cliff-after-the-Road-Runner ending of his own. (This provokes an annoyed Miles Davis to intone, "Play the ending, man, you know that arrangement.") Then follows "Dig," an up-tempo, purely BeBop line over the chords of "Sweet Georgia Brown." (In May 1952 Miles would re-record this piece at a slower tempo, under the title of "Donna".) The solos are all nearly top-notch. Unfortunately, someone in the control booth hit the "reverb" button, and so this track sounds muddy enough (Art Blakey's high-hat cymbals, especially) such that not even Joe Tarantino's 24-bit remastering could add much clarity. (I grew up with the 1970s Prestige LP edition, and this CD sounds about the same.) With "My Old Flame," Miles and Sonny Rollins further develop their mastery of sustained, lyrical narrative. With his dark, vibrato-less tone, Miles increasingly "homes in" on the stylistic Center toward which he was still groping. The session ends with "Paper Moon." Miles, with his attractive dark tone and rhythmically incisive lyricism, is moving toward many future glories. In particular, his "breaks" with Art Blakey (at the point where the song's lyric reads "Without your love") point toward "Four" and "Old Devil Moon" from their session of March 15, 1954. On this track, Miles really leaves you with a sense of hope and well-being, in spite of, and in the midst of, his struggles...Meaning that the Struggle was, and is, worth it. " |

Track Listings (13) - Disc #1

Track Listings (13) - Disc #1