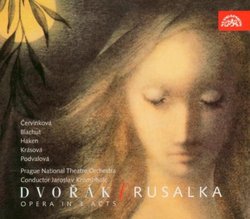

| All Artists: Jiri Joran, Premysl Koci, Antonin Dvorak, Jaroslav Krombholc, Marie Podvalová, Prague National Theatre Orchestra, Ludmila Cervinkova, Ludmila Hanzalikova, Maria Tauberova, Miloslava Fidlerova, Beno Blachut Title: Dvor�k: Rusalka Members Wishing: 1 Total Copies: 0 Label: Supraphon Release Date: 5/31/2005 Album Type: Import Genre: Classical Styles: Opera & Classical Vocal, Historical Periods, Modern, 20th, & 21st Century Number of Discs: 2 SwapaCD Credits: 2 UPCs: 099925381127, 099925381127, 099925381127, 028944637724, 028944637724, 099925381127, 028944637724, 099925381127, 028944637724 |

Search - Jiri Joran, Premysl Koci, Antonin Dvorak :: Dvor�k: Rusalka

| Jiri Joran, Premysl Koci, Antonin Dvorak Dvor�k: Rusalka Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsPITIFUL RUSALKA PALLID DAVID BRYSON | Glossop Derbyshire England | 12/10/2007 (5 out of 5 stars) "This is a set, and indeed this is an opera, that I would like to recommend as strongly as I can, but I think I had better not recommend them under any false pretences. To summarise at the outset what I shall try to substantiate presently, the strengths of Dvorak's Rusalka are all musical, and its shortcomings are all dramatic and literary. Much, maybe most, of the music is Dvorak at his heavenly best, but the libretto is something close to hopeless. With one exception the performers vary from good to wonderful (Blachut), but above all the direction is a priceless memorial of a musical era.

The recording has been given digital remastering in 2005, but If it be long, ay, long ago When I beginne to think howe long since the performance was first captured on record, I find it was as long ago as 1952. At that time the communist authorities in cold war Czechoslovakia were intent on establishing a musical culture that would be pure and untainted by external influences. The comparative isolation of their operatic tradition was a serious handicap in serious ways, but in terms of the performers it had a great deal to be said for it. In Rusalka, as in Smetana's Dalibor, there is a special tone and atmosphere to the playing of Czech orchestras under Jaroslav Krombholc that more than compensates (to my ears) for any lack of refinement they may show when compared with their western counterparts. The singers are equally authentic, and although my own Czech never got far past such oratory as `to je muj bily kolo' and the more frequently used `pivo prosim. Za to stoi?' I think I can still enjoy the sense that these singers are at home with the words. In particular, it is something definitely special to be able to hear Beno Blachut. Where the isolation was a problem was amateurishness on the creative side. Even Smetana, a good orchestral technician as a rule, treats the unfamiliar harp clumsily in Dalibor. Dvorak has surmounted any and all orchestral hurdles (just listen to the superb harp writing in this score), but like Smetana he just takes what he is given by way of a book. What he is given in Rusalka is an overgrown fairy tale, padded out with unnecessary characters to give a few more people something to sing. The story does not amount to much, and in my opinion it will not bear any grandiose analysis trying to find parables and allegories. Two of the main characters are not human - that is the whole point of the tragedy - and it is difficult to convey their injured feelings in any non-human way, so that we are left not knowing how and with whom to empathise. There is no real structure or design to the plot, and although I don't think Dvorak has the basic theatrical sense that enabled Smetana to infuse a certain amount of real drama into the static libretto of Dalibor (which is nearly as bad as this one), there is actually some help that he gives his crippled text from his sheer musical talent. Dvorak is able through his music to give this story pace and fluency. If we stop to think we will realise that the composer is reacting with sensitivity and panache to the various situations as they succeed one another, but that the task of giving real coherency to this story is beyond any composer. Dvorak's achievement is in charming us out of concerns about anything so cerebral as coherency. He does anything that can be done, which is not much, with the plonking repetitions of `Pitiful Rusalka pallid' that are supposed to be some awesome leitmotif and which may sound better in Czech although I wouldn't bank on that. He starts with a prelude of exquisite beauty, but you may need a little forbearance with the first chorus for the three dryads. These may be intended to recall Wagner's Rhinemaidens at the start of The Rhinegold, but they spend nearly five minutes singing very little other than `Ho ho ho', and the effect may seem to you more diverting than inspiring. Keep the faith - from there on Dvorak pours out music of outstanding beauty, spontaneity and freshness all the way to the end. It must be most gratifying to sing, and the singers, except for Marie Podvalova as the Foreign Princess, whose pitch in the more energetic stretches of yelling about could be politely characterised as `approximate', really do very well. The Water Sprite, Rusalka herself, and the Witch give me few problems, but of course the star is the great and unique Blachut, although perhaps his special quality comes over even better in and as Dalibor. The chorus is full of life and verve, and I have already mentioned the orchestra. There is an elaborate and earnest liner essay, there are profiles of all the principals including Krombholc, and the full libretto is given in Czech, English, German and French. The recording is not bad at all as remastered. It is very clear and the balance of voices against orchestra is excellent. There are some uncomfortable moments with high notes, but not all that many and mainly in connexion with Podvalova for whatever reason. My strictures on the libretto, and to a much lesser extent on the music, have been in the interests of trying not to mislead any newcomers about what they can expect to find. In fact it is gorgeous music for the most part, and I find it hard to suppose that any music lover in tune with the late romantic idiom could possibly fail to enjoy the production, at least as presented to us here. I suggest that this set is well worth collecting, and if you like what you have collected add Krombholc's Dalibor as an extra Christmas treat for yourself, or for whoever you feel deserves it." |

Track Listings (12) - Disc #1

Track Listings (12) - Disc #1