America's Pavarotti

Samuel Chell | Kenosha,, WI United States | 03/25/2007

(5 out of 5 stars)

"Jug was a class act with a heart as big as his physical size and tone. Chicagoans greeted him like a war hero on the two occasions he appeared just after doing time at Joliet-- the second an especially cruel and unfair sentence of seven years for a parole violation. Because he usually followed Sonny Stitt--the "most perfect" of all players--in their tenor battles, he had the advantage of playing to low expectations--and he rarely failed to rise to the occasion. In fact, just being able to match Stitt was sufficient to assure a victory.

Stitt, the saxophonist most identified with Charlie Parker and reputed to have been bequeathed the "keys to the kingdom" by Bird himself, would seem to outmatch Ammons. But those listeners with longer memories or inclined to do a bit of research would know better than to underestimate Jug, the son of the highly regarded Kansas City boogie woogie pianist, Albert Ammons. Gene was still in his teens when Billy Eckstein hired him to sit next to Dexter Gordon in the same big band that included Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, Kenny Dorham, and Fats Navarro, not to mention Charlie Parker, Sonny Stitt, Wardell Gray, Art Blakey and Sarah Vaughan! At the end of his sets in the late '60s and early '70s, Jug used to love running down the line-up for his audience, all of it building up to his dramatic punch-line: "And what were all of these musical geniuses doing night after night?" (Pause) "Holding whole notes while Mr. B was balladeering on his hit songs, "I Apologize," "I Want to Talk About You," and "I'm Just a Prisoner of Love." (Pause) Who was a prisoner?"

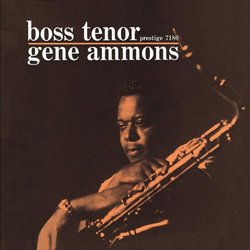

The present RVG remaster captures Ammons at an optimal time. Following his last stay at Joliet, Jug would be greeted by a musical scene radically different from the one that he had left--Coltrane, Hendrix, Joplin not to mention the Beatles and Stones had reshaped the sonic environment he was accustomed to. Unfortunately, Ammons tried to adjust with uncharacteristic altissimo shrieking and forced elocution leading to unmistakable intonation problems. But Boss Tenor, recorded in 1960 and with the supremely gifted, exquisitely tasteful Tommy Flanagan on piano, finds Ammons with nothing to prove and doing what he did best--creating beautiful, heart-felt yet logically-constructed melodies and producing a sound that for many listeners has never been equaled--big but never "hard," simple and slightly raw but too lyrical and personal to be mistaken for R&B. True, it was gospel and blues-derived but free of any Motown shine and polish.

Recently I read a review crediting Ammons with inspiring R&B sounds of pop saxophonists like Junior Walker. If there's any question about the difference between a Junior Walker and a Gene Ammons, go directly to "My Romance," more full-bodied and sensual but no less sensitive than Bill Evans' version on the original Vanguard sessions. Ammons takes the tune through once, entrusting Richard Rodgers' poetic melody to the breathstream of the tenor's seductive voice, as reassuring as it is alluring. In short, it's as good a sound as the tenor saxophone is capable of producing. So, too, in a battle of tough tenors Ammons could play one note for the hundreds spewed forth by a Sonny Stitt or Johnny Griffin. Invariably, it was the right note."

Track Listings (7) - Disc #1

Track Listings (7) - Disc #1