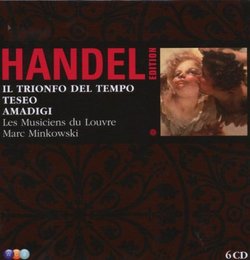

| All Artists: George Frederick Handel, Marc Minkowski, Aline Zylberajch, Thierry Schorr, Della Jones, Eirian James, Pascal Bertin, Les Musiciens du Louvre, Emmanuel Mandrin, Catherine Napoli, Eiddwen Harrhy, Isabelle Poulenard, Jennifer Smith, Julia Gooding, John Elwes Title: George Frideric Handel: Il Trionfo del Tempo e del Disinganno; Teseo; Amadigi di Gaula Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Warner Classics UK Release Date: 2/17/2009 Album Type: Import Genre: Classical Style: Opera & Classical Vocal Number of Discs: 6 SwapaCD Credits: 6 UPC: 825646965199 |

Search - George Frederick Handel, Marc Minkowski, Aline Zylberajch :: George Frideric Handel: Il Trionfo del Tempo e del Disinganno; Teseo; Amadigi di Gaula

| George Frederick Handel, Marc Minkowski, Aline Zylberajch George Frideric Handel: Il Trionfo del Tempo e del Disinganno; Teseo; Amadigi di Gaula Genre: Classical |

Larger Image |

CD DetailsSimilarly Requested CDs

|

CD ReviewsSHOULD BEAUTY INDULGE HERSELF? DAVID BRYSON | Glossop Derbyshire England | 06/27/2009 (4 out of 5 stars) "This is a very important reissue, and I want to recommend it strongly despite a certain reservation (which I shall explain and which you may not even agree with) that stops me from awarding all 5 stars. It combines on 6 very well filled cd's three earlier releases that presumably did not fly off the shelves, so here they are going for - not exactly a song, but you know what I mean. The two operas, Teseo and Amadigi, have probably been very little performed since Handel's own time, and these recordings are either their first or almost their first. The importance of this is in advancing our knowledge of Handel, considered by Beethoven `the greatest composer who ever lived'. I don't think it depends on whether we agree literally with Beethoven to see just what the magnitude of this claim is. Give or take any refinements in the meaning, here is no mean judge proclaiming a composer to be `greater' than Bach and Mozart, so for me it is a high priority to understand the claim as best I can, and in the process try to account for the barriers to acceptance that have kept Handel out of the mainstream of our musical tradition. By that I mean that although matters have improved out of recognition in the last 50 years, we are still only gradually getting the opportunity to know most of his enormous output, bigger, I am told, than the total surviving opus of Bach and Beethoven combined.

At the popular level, Handel had become famous for overblown performances of a restricted part of his output, and he was the unwitting progenitor of a tradition of choral works that should have been stifled at birth. At the intellectual level, even distinguished musical scholars had to produce books on Handel when most of his work was no longer performed, putting them in the ridiculous position of not having something to say but having to say something. A proper performing tradition has been revived for works of the period, and Handel has benefited hugely, but the critical tradition is still labouring from its heritage, and music lovers eager to get a sound understanding of the composer and his real significance cannot be sure who and what to believe. In particular Handel's operas have still to establish themselves firmly in the repertory; and that of course is where this set is so important. The specialist interpreters of early music are a high-powered crowd, and Marc Minkowski is a big name among big names. You would expect a distinguished production here, and you will get one. The performers' grasp of the idiom is meticulous, the orchestral instruments are `period' instruments, the singing is in the style now recognised as appropriate as well as being brilliantly accomplished in the technical sense, and the recordings (Amadigi apparently from a broadcast) are clear and natural. The readings are full of vivacity with great drive and virtuosity in the vigorous numbers, while at the same time Minkowski has no problem with taking really slow tempi for the more soulful arias, many of which are exquisite and demand every ounce of expressiveness that the performers can muster. There are no choral numbers, so the focus is relentlessly on the soloists, and naturally the standard is not totally even. These 6 discs contain as many arias as would 40 Bach cantatas, and I have no problem at all with some very minor and infrequent lapses of pitch. The name of Nathalie Stutzmann was one I recognised from my growing collection of Gardiner's `pilgrimage' series of the said cantatas, and she is a jewel here as much as there. I thought that the sopranos Isabelle Poulenard and Jennifer Smith were excellent too, and while Eiddwen Harrhy as Melissa in Amadigi may lack something in refinement, again I had no serious issue with her, nor have I much criticism to offer of Bernarda Fink, the Dardano in Amadigi. In Teseo Eirian James in the title role is rather so-so, but Della Jones, Julia Gooding and Catherine Napoli do really very well. There are two counter-tenor roles in Teseo, and I have never outgrown a certain feeling of discomfort with this type of voice. I prefer the voice of Jeffrey Gall to that of Derek Lee Ragin, but that is purely a matter of personal taste, and there is no disputing the technical brilliance of either, Ragin in Serenatevi and Gall in Benche tuoni. My `problem', if it is one, is highlighted by Il Trionfo, where I actually have something to compare with this reading. This work is given here in its original 1707 Italian version, with no chorus. Handel revised it twice, first under a slightly modified Italian title in 1737, then right at the end of his life in an English version with choruses called The Triumph of Time and Truth. Drastic though the revision is, it was still reasonable to compare my Hyperion disc of the English work from the London Handel group just to make a general comparison of the styles. And doing that left me in no doubt that the Hyperion account is simply a lot more beautiful. For all the understanding and proficiency that Minkowski shows, he is just a bit austere for me. The quality of the arias here rivals Bach's own, but it takes more effort to get to know them. For all Bach's legendary academic manner, his arias are catchy in a way Handel's are not, for various reasons. Bach's rhythms are much simpler for one thing, and everything he wrote, even his vocal music, is an abstract musical pattern, while Handel is writing dramatic stage numbers. Another factor, one that we probably don't like to admit, is that we usually care less about the words than we do about the music going with them, and whereas in Handel the voices are what it is all about, in Bach they are really subordinate to his gorgeous obbligato instrumental parts. This makes it all the more important to work to convey the full sensuous beauty of Handel's arias. Pene tiranna from Amadigi is probably a knockout to rival, say, Schlummert ein from Bach's cantata 82, but the director has to be willing to yield a little, although I admit that repeated hearings are lowering my own resistance to his style. In Il Trionfo Beauty is made to renounce her dalliance with Pleasure and recognise the claims of Time. There is no getting away from those, although anyone who has French may like to read Villon's poem Heaulmiere's Lament, in which the effects of time on the female form are described less complacently and in considerable anatomical detail. For present purposes, while I admire and value this set greatly, I just wish that the director had let Beauty and Pleasure present a more united front." |