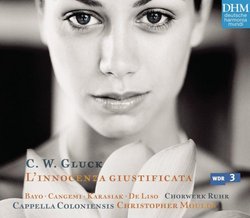

| All Artists: Christoph Willibald Gluck, Christopher Moulds, Marina De Liso, Capella Coloniensis Orchestra, Cappella Coloniensis, Maria Bayo, Veronica Cangemi, Andreas Karasiak Title: Gluck: L'innocenza giustificata Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: RCA Release Date: 5/4/2004 Genre: Classical Styles: Opera & Classical Vocal, Historical Periods, Classical (c.1770-1830) Number of Discs: 2 SwapaCD Credits: 2 UPC: 828765879620 |

Search - Christoph Willibald Gluck, Christopher Moulds, Marina De Liso :: Gluck: L'innocenza giustificata

| Christoph Willibald Gluck, Christopher Moulds, Marina De Liso Gluck: L'innocenza giustificata Genre: Classical |

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsVIRGINITY TRIUMPHS DAVID BRYSON | Glossop Derbyshire England | 05/04/2004 (5 out of 5 stars) "Technically speaking, this attractive and most enjoyable musical tableau is not strictly an `opera'. It is a `festa teatrale', differing from opera seria in having only two acts not three, in having little or no overt `action' and in steering clear of the more harrowing emotions. The librettist is not known for a certainty, but it seems likely to have been Count Durazzo, a kind of Genoese cultural attache at the imperial court in Vienna. The story is of a kind at which Gluck excelled - all statuesque marmoreal classical figures expressing dignified and edifying sentiments. As usual from Gluck irrationality, irrelevance and stagy operatic nonsense generally are sternly excluded. At his best, Gluck is hard to beat. He was not an accomplished composer in the technical sense as Handel caustically pointed out, averring that his own cook, a gifted singer called Walz, knew more counterpoint than Gluck did. Gluck's music depends entirely on inspiration, lacking the professional resourcefulness that almost any other composer of comparable stature would have thought indispensable, but when the inspiration is on him that never seems to me to matter, and his unflinching rationality is always a dependable bonus too.The legend here is found in both Livy and Ovid. Claudia, one of the Vestal Virgins charged with keeping the sacred flame alight, faces the double accusation of letting it go out and also of behaviour alleged to have been other than vestal with a young Roman knight Flavius. For this she is condemned to death unheard by the Senate, a sentence enthusiastically endorsed by the Roman mob. Meantime a ship carrying the sacred statue of the Bona Dea runs aground in the Tiber, a manifest omen of displeasure from the gods. The entire manpower resources of Rome cannot pull it clear, but Claudia does so unaided, thus demonstrating her innocence and bringing about an instant change of heart in those who only a moment earlier had been denouncing her. This may have been a basic Roman characteristic, because Tacitus notes regarding the quick-fire succession of Emperors in 69 AD `Alium crederes populum, alium senatum - you would have thought it a different populace and senate' - when these turn like a weather-vane from applauding one conqueror to applauding the next. The music is mainly recitative and aria, two of the arias near the end being of the cavata/cavatina/arietta type with no middle section leading to the usual repeat of the first part, but the plot also requires a chorus of `senators, knights, lictors and people' to quote the liner-booklet. To my ears the arias are simply superb. I have an enormous liking for Gluck's very individual personal idiom - it would be completely impossible to mistake him for Handel or for Mozart, or indeed for anyone other than himself. The performance has the out-and-out professionalism that I am increasingly coming to associate with the current crop of early-music specialists. Like their English counterparts, the Cappella Coloniensis are distinguished for team-work, with their soloists giving polished, assured and idiomatic accounts of their parts rather than providing star turns. Flavius is in fact sung by a soprano, the lowest of the four parts is the tenor role of Valerius, and I find that the overall effect is one of very pleasing lightness in the timbre. The accompanying booklet is also thoroughly professional in every respect, particularly the essay by the admirable Sabine Radermacher. The recorded quality is faultless too, and while I wondered whether the music could not have been shoehorned into a single disc rather than two, it would have been a tight squeeze at best and I make no complaint."

|