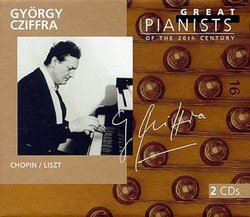

| All Artists: Gyorgy Cziffra, Chopin, Liszt Title: Gyorgy Cziffra - Great Pianists of the 20th Century Members Wishing: 3 Total Copies: 0 Label: Philips Release Date: 6/1/1999 Genres: Dance & Electronic, Special Interest, Classical Styles: Exercise, Chamber Music, Forms & Genres, Fantasies, Short Forms, Historical Periods, Classical (c.1770-1830), Modern, 20th, & 21st Century Number of Discs: 2 SwapaCD Credits: 2 UPC: 028945676029 |

Search - Gyorgy Cziffra, Chopin, Liszt :: Gyorgy Cziffra - Great Pianists of the 20th Century

| Gyorgy Cziffra, Chopin, Liszt Gyorgy Cziffra - Great Pianists of the 20th Century Genres: Dance & Electronic, Special Interest, Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsNo Brakes Charles Milton Ling | 01/08/2002 (5 out of 5 stars) "I give this collection 5 stars because I know of no recorded piano playing like it (except other earlier Cziffra recordings such as the "Live in Italy" stuff which I haven't seen available in years). I don't mean to imply that it's necessarily more impressive than Horowitz during the great days (the "Homage to Liszt" album must be some sort of unique standard in all of pianism) or some of the best playing by Byron Janis (Liszt Concerti, for example) or Argerich's best et al. It is different, though, in its unique combination of speed, power and knife-in-the-teeth abandon. The Liszt disc is far more "chaste" than the Chopin Etudes which, let's face it, often sound like the musical equivalent of a fun-house mirror. I bumped into the recording while I was in London in 1964 or '65, took it back to my student colleagues at the Oberlin Conservatory (all aspiring pianists, as I was then) and it became the hands-down Friday night favorite (along with Gallo Sherry, if I remember correctly, and Nancarrow Etudes for Player Piano). Some of the virtuosity can scarcely be believed -- such as the Op. 10 #4 (but Richter is even faster on the "Richter The Enigma" video, if you can imagine) -- the Op. 10 #12 and the "Octave" Etude from Op. 25. But he DOES struggle terribly with Op. 10 #2 (compare it to the early Ashkenazy which is mind-boggling) and many of the other pieces are simply stomped through without any concern for phrasing or architecture. But what a wild ride! And what guts to record them this way! (Recommendation: if you can find the old Paul Badura-Skoda recording of the complete Chopin Etudes, don't hesitate. I know it seems an unlikely pairing of pianist and music, but just listen! The fastest Winter Wind ever, the most amazing Op. 10 #1 except for Anievas, etc. etc. And, by the way, why is Cziffra's "Winter Wind" a half tone sharp? Of all pianists, he doesn't needed to be tempo twisted.)I said the Liszt was more "chaste" but don't mean to imply it's less virtuosic than the Chopin. It comes from an era when I would guess Cziffra wasn't bored with the music or, to put it another way, didn't see a need to fuss with phrasing just to keep himself interested. Compare, for instance, the first set of Liszt Hungarian Rhapsodies with the one recorded for EMI in the mid 70's. The later interpretations, once again, are beginning to sound neurotic -- even psychotic -- and the pianistic mechanism has started to fade somewhat, but wow what a trip. The end of the Ninth Rhapsody (Carnival of Pest) or the end of the Thirteenth is like being on a rollercoaster with no brakes and the tracks out ahead . . .I guess my attraction for the best of Cziffra's playing is the sense that there's something of a struggle involved pianistically (even though the "Live from the BBC" video shows a man scarcely breaking a sweat) and also the feeling that he was a spirit who had to overcome so many social, political and personal problems. I'm afraid I can't agree that Cziffra's playing was superior to Horowitz's in any fashion whatsoever. And yet I constantly cull the bins to see if there's a forgotten Cziffra album or CD out there. I can't say that about Horowitz. In any case, my strong recommendation is to buy these discs, put on a hat, and hold on to it." A portrait of a sadly under-rated master Charles Milton Ling | Vienna, Austria | 11/22/1999 (5 out of 5 stars) "Two things first. I wrote "master", not "virtuoso" quite intentionally. And yes, Cziffra was the virtuoso supreme of the instrument he had made his own, and vice versa. I wrote "master" because Cziffra's abilities extended far beyond his spectacular ability to make the piano his servant; to transcend all the obstacles a composer may have placed in his way. There is much more to Cziffra than we will learn from these CDs; but from these CDs we will learn why the mere mention of Cziffra's name can take the breath away of those who were fortunate enough to see him, and indeed also of those he taught. "A Keyboard Master and His Limitations" is the translation of the heading Peter Cossé gives to his - masterful indeed - comments on these CDs. A more literal translation would have been "The Almighty and His Limits". Yes, as far as technique is concerned, Cziffra is second to none. This is displayed to brilliant, almost disconcerting, effect on the CD works by Liszt. It has to be heard... Chopin? To be quite honest, I feel Cziffra does several of the études a disfavour by demonstrating how excitingly/quickly they can be played (by him). These, then, are the limitations posed by a brilliant talent unreined. But in op. 25 nos. 10 - 12, we are on ground where only the most capable should dare to tread. Cziffra's interpretation has no equal. For this alone, this CD is more than worth its price. This is one of the most important moments in pianism. To say more would be to say less." SOME KIND OF ULTIMATE DAVID BRYSON | Glossop Derbyshire England | 08/11/2003 (5 out of 5 stars) "I guess that if you like Horowitz you will like Cziffra. His career was all too short, ending abruptly on the tragic death of his son. He was a Hungarian gipsy born in 1921 and dying in 1991, the year that also saw Serkin, Kempff and Arrau summoned away in short order. By now I have lost track of the pianists I have seen described as ultimate technicians -- Hofmann, Rachmaninoff, Horowitz, Michelangeli, Argerich, Pollini, Gavrilov, Kissin and of course the obligatory Richter among others. My own two finalists in that particular competition would be Michelangeli and Cziffra. Michelangeli is sui generis, a different pianistic animal from any of the others. Cziffra is in something like the 19th century virtuoso tradition as I know it from Hofmann and Rachmaninoff. Speeds are typically fast, as they were from Rachmaninoff, and virtuosity is a key element in Cziffra's way of expressing the music. This is entirely as it should be in my opinion. When Cziffra's career was at its height something dangerously like staidness was in vogue, and something known as 'virtuosity for its own sake' was widely viewed as a Bad Thing. I have never even known what it was supposed to be, let alone why it was such a bad thing, but I recall Cziffra falling foul of this particular critical waffle, and it goes a long way to explain why he is not better known. Anyway Cziffra treated technical brilliance as an integral part of the musical expression in certain pieces, and rightly so say I. Why playing brilliant pieces in an unbrilliant way should be considered a plus for expressiveness is the bit I have never understood.

The recorded sound is rather hard in the Chopin studies, much better in the Polonaise, where it is interesting to compare him with Horowitz. In the middle section both are absolutely dumbfounding, the main difference being that Cziffra does not go through his tone as Horowitz does. This was something that Horowitz carried off with aplomb, but something everyone else has had the good sense not to copy. Where I like Cziffra very much better is at the start, where Horowitz deploys a peculiar dry touch that he was sometimes prone to adopt on inappropriate occasions. Rubinstein pedals heavily here, which is fine by me, but Cziffra's finger-legato is easily the best way. In the studies I would not say that I prefer Cziffra to the fine sets by Ashkenazy (here at his all-too-rare best) or Pollini. It's near-impossible to rank three such players in 24 short pieces. What I would ask you not to believe is the booklet, which nearly falls into the 'virtuosity for its own sake' morass. There is plenty of soul and expressiveness from Cziffra here, although the hard recorded sound doesn't help. I don't believe, for instance, that Cziffra banged at the bass in the 'butterfly' study or the one in sixths the way he comes across as recorded here. In the Liszt pieces if you take away the virtuosity there is little or nothing left, but virtuosity plus belief like this almost had me taking them seriously as music, which is saying a lot. They are simply astounding, and I apologise for using such a term to anyone who is as weary of it as I am. This time it's true. In the very last resort Cziffra seems to me even more of a virtuoso wonder than Horowitz, and this playing is full of heart, soul and fire. I do not know whether as a Hungarian Cziffra represents some specially authentic Lisztian tradition. What I do know is that he does more for Liszt as far as I am concerned than anyone else has ever done.There is actually an account of the op25 Chopin studies that is surprisingly like Cziffra's. It is a historical reissue, it is not madly well recorded, and it comes from a quarter you might not expect. It is by Serkin, and it comes with the new biography of him issued earlier this year." |

Track Listings (11) - Disc #1

Track Listings (11) - Disc #1