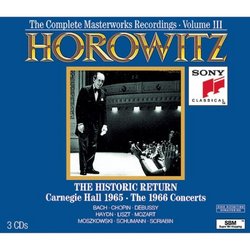

| All Artists: Johann Sebastian Bach, Robert Schumann, Alexander Scriabin, Frederic Chopin, Claude Debussy, Moritz Moszkowski, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Franz Joseph Haydn, Ferruccio Busoni, Franz Liszt, Vladimir Horowitz Title: The Historic Return: Carnegie Hall 1965; The 1966 Concerts Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Sony Original Release Date: 1/1/1994 Re-Release Date: 6/14/1994 Genres: Dance & Electronic, Classical Styles: Forms & Genres, Ballads, Fantasies, Short Forms, Sonatas, Historical Periods, Baroque (c.1600-1750), Classical (c.1770-1830), Modern, 20th, & 21st Century Number of Discs: 3 SwapaCD Credits: 3 UPC: 074645346120 |

Search - Johann Sebastian Bach, Robert Schumann, Alexander Scriabin :: The Historic Return: Carnegie Hall 1965; The 1966 Concerts

| Johann Sebastian Bach, Robert Schumann, Alexander Scriabin The Historic Return: Carnegie Hall 1965; The 1966 Concerts Genres: Dance & Electronic, Classical

Sony's series documenting Horowitz's mature career offers many indispensable items, including "live" (with studio touchups) recordings of his mid-1960s return to the concert stage after a prolonged hiatus. The Bach-Busoni ... more » |

Larger Image |

CD DetailsSynopsis

Amazon.com essential recording Sony's series documenting Horowitz's mature career offers many indispensable items, including "live" (with studio touchups) recordings of his mid-1960s return to the concert stage after a prolonged hiatus. The Bach-Busoni is a dazzling opener, followed by a titanic Schumann Fantasy in C amply illustrating Horowitz's total identification with the composer. The performance abounds with tightly controlled nervous energy, precise articulation, and gorgeously shaded timbres. A crisp Haydn Sonata, a marvelously shaded Scriabin, a poetic Schumann Traumerei, and more are all indispensable. Not to be missed: the pregnant pauses and crackling tension of the Chopin G-minor Ballade. --Dan Davis Similar CDs

Similarly Requested CDs |

CD ReviewsA gigantic recording Hans U. Widmaier | Elmhurst, IL USA | 02/20/2001 (5 out of 5 stars) "There's an interesting debate going on in the reviews below about Horowitz's technical and musical ability in general. Do yourself a favor and read through these reviews. It'll show you that Horowitz's ability to engender strong positions and fairly heated exchanges continues undiminished, more than eleven years after his death. What this proves, of course, is his uniquely important position in 20th century piano playing. No other classical pianist was as influential, no one's style was copied as much, no one was as frequently and thoroughly misunderstood (mere technician, mere dazzler, mere showman). What you have to understand in listening to these recordings is that he was a complete professional, totally devoted to his craft to the exclusion of just about any other interests in his life - a tremendously one-sided person. But within the art of piano playing he reigned supreme. His oddly introverted, unmoveable, purely efficiency-oriented appearance during performance (he never moved anythying but his hands - no facial contortions, no head shakes, no swaying body, and even his hands were super-efficient) contrasted oddly with the extreme extrovertedness of his playing. He knew so much more about the sound possibilities of the instrument than anyone else that listening to him was downright frightening for other pianists. I remember a well-known pianist during intermission at a Horowitz recital in Hamburg in 1986 laughing and crying at the same time, shaking his head and saying over and over again, "it's impossible. That was impossible. That can't be done" (he was talking about Horowitz's rendition of a Schubert-Liszt transacription). Anyway, his mastery of the instrument far beyond all other humans' capacity has persistently clouded people's perception of Horowitz and made an assessment of his artistic merits much more difficult. Undoubtedly he had clear limitations as an artist (Beethoven, for example, was just not part of his artistc world). But we have to keep in mind that, unlike practically all classical musicians today, who are trained to be universalists and to assemble a vast variety of styles, Horowitz came out of a strong and idiosyncratic musical tradition - that of Scriabin and Rachmaninov. That tradition was his world, his artistic home, and he always explored other musical traditions from the vantage point of his particular musical identity. In all of this he proved extremely flexible (playing, for example, Scarlatti, Clementi and Czerny to great critical acclaim), but since he never aspired to neutrality and objectivity (like, for example, Pollini or Arrau), it always was obvious when he played music that didn't fit with who he was.So the debate about Horowitz's musical merits that goes on in the reviews below is as old as his career. What's curious, though, is that a couple of reviewers believe to have found TECHNICAL shortcomings in his playing. That is new in Horowitz criticism. All his career he reigned as the supreme master of piano technique, acknowledged as such first and foremost by most famous pianists (Rubinstein, Argerich, Pollini, Perahia, and many others have rhapsodized - or expressed their jealousy - about Horowitz's technique publicly and at length). When speed and power decreased due to old age, he transferred his technical accomplishments to polyphony, to shadings, colors, multi-layered pianissimi unimagined before or after. In the present recordings from the mid-60s, there was no noticeable decrease in speed and power yet, but his development toward more sophisticated sound effects was well underway. In other words, the questioning of Horowitz's technical abilities in some of the reviews below is utter and complete nonsense. I can only surmise that the authors of these reviews are people raised on the bland, impersonal mechanical functioning displayed by so many contemporary pianists that Horowitz's edginess, his constantly going to extremes (of speed, of clarity, of softness, of bel canto, etc.) irritates them somehow. One thing Horowitz was never after was a polished surface. If you want pleasant, comforting stuff that you can play happily in the background while doing the dishes, Horowitz is not the artist for you. He demands total concentration. But he'll reward that concentration tenfold. Even if you don't agree or don't like what he does in a particular piece, you'll learn a ton about music listening to him. He's a very musically opinionated guy, and some of his work may irritate you a great deal, but he will never, ever bore you." One of the great piano recordings of all time Hans U. Widmaier | Elmhurst, IL USA | 12/09/1999 (5 out of 5 stars) "In May 1965, Vladimir Horowitz, the greatest pianist of all time, ended a 13-year retirement and returned to Carnegie Hall. The audience contained many of the world's most famous musicians, and playing up to its frenzied expectations seemed impossible. Horowitz begins, tense to the breaking point. For a few seconds, his hands are out of control, and he hits more wrong notes than right ones. Then things settle a bit, and he starts to translate his tension into pure musical energy. In that first piece, the Bach-Busoni, Horowitz seems almost superhuman with his orchestral sound, his sharp rhythm, his alternatingly hard-edged attack and meltingly lyrical lines, his supreme intelligence. It must have been immensely frustrating for the pianists in the audience to be so rudely confronted with such hopeless pianistic superiority. The Bach is followed by a highly idiosyncratic Schumann Fantasy, where Horowitz shows a grasp of the work's structure and an analytic penetration of Schumann's neo-Bachian polyphony undreamt of by any interpreter before or after. The recital continues with musical and pianistic jaw-droppers. I single out the Chopin and Moszkovski Etudes, where the audience's incredulity at Horowitz's feats dissolves in laughter at the end of the pieces, the tenderness and intimacy of Debussy's Serenade for a Doll, and the truly moving Schumann Traeumerei. The remainder of this CD collection contains 1966 live recordings, many of which are as fascinating as the '65 concert. Particularly noteworthy are the Haydn Sonata for its dry wit, Chopin's Polonaise-Fantasie for the almost infinite range of expressions and emotions Horowitz creates, and Liszt's Vallee D'Obermann, which inspires Horowitz to the most atmospheric, most evocative music-making I have ever heard on a recording. In sum, if I knew I would lose my hearing in a few hours, I would spend them listening to these recordings." Beautiful piano playing Scott Elder | Houston, TX USA | 11/17/2000 (4 out of 5 stars) "I am writing in to disagree a bit with the previous reviewer who dismissed this recording and Horowitz's playing in general. I would agree that this is not Horowitz's greatest recital. It may be better remembered for its historical significance than as a representative sampling of Horowitz's art. For me, much of the repertoire in this recital could be called "ill-chosen." The pieces such as the Schumann Fantasie, the opening Bach piece, and Chopin's g minor Ballade do not really show Horowitz at his best -- and not just because they're "big" pieces that "require interpretation." Aside from the Chopin Ballade, these are not pieces that one would typically hear at a Horowitz recital, and I do wish that he had not insisted on repeatedly performing and recording the g minor Ballade. I agree that his bombastic, episodic approach never worked with that piece. I tend to favor the pieces on this album that were recorded in the 1966 recitals, including the Chopin Polonaise-Fantasie dismissed by the previous reviewer. Yes, the ending is too bombastic, but there is so much beautiful, gorgeous piano playing in this performance. The way Horowitz could layer the sound and produce such a beautiful, expressive, vocal melodic line can perhaps be fully appreciated only by real connoisseurs of piano playing. Horowitz was not just a pianist for the "masses." He was also a pianist for connoisseurs.Is it possible to acknowledge the shortcomings in Horowitz's technique and interpretive ability pointed out by the previous reviewer and to still be a great fan and admirer of his playing? Yes, it is. I know that many listeners who hear the shortcomings in Horowitz's playing feel that Horowitz's admirers must lack discrimination, and I think that in some cases this is true. In fact, I sometimes think that critical reaction to Horowitz can be roughly divided into three categories: The first category would be for unconditional admirers of Horowitz who feel that he could do no wrong. I would say that this represents the least perceptive evaluation of Horowitz's playing. The second category would be for people who are aware of the shortcomings in Horowitz's technique and musicality and who feel justified in dismissing Horowitz because of these shortcomings. I think that this view represents a somewhat more perceptive evaluation of Horowitz, and I think that the previoius reviewer would fall into this category.The third category would be for people who are aware of the shortcomings in Horowitz's technique and musicality and who still feel that he was one of the greatest pianists in history. In my opinion, this is the most perceptive evaluation of Horowitz's playing.I, too have listened to all of Horowitz's recordings, and have come to a different conclusion about his playing than the previous reviewer. For me, this recording is certainly worth having, mostly for the 1966 recordings."

|

Track Listings (8) - Disc #1

Track Listings (8) - Disc #1