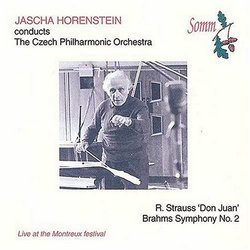

| All Artists: Johannes Brahms, Richard [1] Strauss, Jascha Horenstein, Czech Philharmonic Orchestra Title: Jascha Horenstein conducts the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Somm Recordings Release Date: 9/28/2004 Genre: Classical Styles: Forms & Genres, Theatrical, Incidental & Program Music, Symphonies Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 675754772222 |

Search - Johannes Brahms, Richard [1] Strauss, Jascha Horenstein :: Jascha Horenstein conducts the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra

| Johannes Brahms, Richard [1] Strauss, Jascha Horenstein Jascha Horenstein conducts the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsStereo broadcast of Montreux Festival concert: Viva Horenste Dan Fee | Berkeley, CA USA | 04/13/2006 (5 out of 5 stars) "So of course you are probably looking at this item because you are already a fan of the late Jascha Horenstein. If not, maybe you will become a fan after your hear the unique combination of instrumental acuity and interpretive genius that he typically brings to his leadership, especially when he gets to work with a band that is better. (Too bad JH never really got a long-term post with one of the better orchestras, though he did have an extraordinary run with London orchestras in the last period of his life.)

So to the CD at hand. This is a release of what seems to have been a broadcast concert from the Montreux Festival, in 1966. The band is the highly regarded Czech Philharmonic. The repertoire at hand includes the Strauss tone poem, Don Juan, and the entirely lovable Brahms Symphony 2. The sound is good, if typical of vintage stereo radio in Europe in its era. The bottom end has just a passing touch of venue tubbiness at times, but not so much nor so often as to betray the otherwise very listenable sound quality. So far as the Strauss tone poem goes, Horenstein leads the Czechs in delivering his trademark blend of brilliant instrumental precision, and musical depth of insight into the late Romantic Era literature: Music as story-telling. The Czech players take turns in various departments, as Strauss gives them fabulous solo opportunities. There is plenty of vigor on display, but the more languorous moments are what really shine here. Like Toscanini talking about Bruno Walter, when Horenstein hits something really nice, his interpretations have a pronounced tendency to go all tingly, without disrupting the tempo one bit. Then we get to the Brahms 2nd. I still remember another radio broadcast of this symphony, with Horenstein leading the Danish Radio Orchestra if I remember it right. Some passing balances in that performance weren't perfectly right, but the dedication and grandeur of Horenstein's overall approach held true nonetheless. In this go, with the Czechs playing at a bit higher technical level, there are no balance problems, passing or staying. The clarity Horenstein encourages from the Czechs reminds me of old George Szell leading Cleveland; but there is much more involvement on behalf of conveying Middle European and/or Jewish soul. Horenstein does not command the Czechs to take the first movement repeat, though he apparently sometimes did in other concerts. I for one would not have minded in he had. The first movement has plenty of drama and fire, despite its pastoral associations in some quarters. The remaining three movements are also just fine. The excellent Czech soloists continue to work their magic as Brahms offers them a passing spotlight in this or that passage. A very light touch of vibrato in the French horns may give us a second's pause, but even then the horns can muster considerable brass burnish when they need to do so. (Remember this is all live. No later touch ups on offer.) The Adagio is not without its shadows, darkening, and is taken consistently at an alive, moving pace. The subsequent Allegretto is as grazioso as anyone might wish. Its woodwind inflections sound a tad more rustic than usual. One of Horenstein's happy capacities is revealed when we hear how well he keeps this movement swinging and singing and flowing along, while at the same time keeping the orchestral texture quite clear, and still not interpretively slighting the gruff, melancholy side of the composer's narratives. A spirited Finale brings all this to a close, just as we expect. Yet all the vigor and activity of the last movement do not brush aside what we have learned about life, listening to the shadows and the cheer and the warmth of the inner movements. It is difficult to put into words just how Horenstein manages this sort of cumulative narrative musical magic. By the end of this Finale, you feel you have been carried along in a greater symphonic story that is much more than the happenstance sequence of four separate movements, assembled in name only to make a symphony. This way of doing the second symphony somehow mysterious points forward to the third symphony that would follow, subtilizing the complexities of its musical argument, deepening in intellect while not stinting one whit on the many beauties which may first draw us as listeners into Brahms' sound worlds. Instead of making the second symphony sound like nothing more than an autumnal, pastoral contrast with the third to come, Horenstein somehow manages to make it a sibling music, not so entirely unlike the third. Highly recommended, then. Do check out the Brahms First Symphony with the LSO, and maybe too, the Dvorak New World with the Royal Philharmonic. One only wishes Chesky and other small labels could afford to remaster these tremendously valuable recordings in SACD sound." |

Track Listings (5) - Disc #1

Track Listings (5) - Disc #1