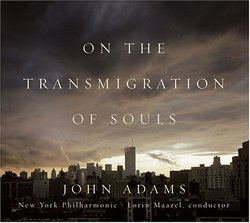

| All Artists: John Adams, Lorin Maazel, New York Philharmonic Title: John Adams: On the Transmigration of Souls Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Nonesuch Release Date: 8/31/2004 Genres: Dance & Electronic, Classical Styles: Techno, Symphonies Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPCs: 075597981629, 075597981667, 755979816298 |

Search - John Adams, Lorin Maazel, New York Philharmonic :: John Adams: On the Transmigration of Souls

| John Adams, Lorin Maazel, New York Philharmonic John Adams: On the Transmigration of Souls Genres: Dance & Electronic, Classical

This is the first recording of Adams's On the Transmigration of Souls (which won the 2003 Pulitzer Prize in music), by the orchestra and conductor that commissioned and premiered it. Adams grips from the start, with a slow... more » |

Larger Image |

CD DetailsSynopsis

Amazon.com This is the first recording of Adams's On the Transmigration of Souls (which won the 2003 Pulitzer Prize in music), by the orchestra and conductor that commissioned and premiered it. Adams grips from the start, with a slow buildup of taped mundane city sounds, the obsessively repeated word "missing" superimposed on them. The taped texts are drawn from fragments found on missing person posters, newspaper memorials, and the names of victims of the 9/11 attack. Sometimes the taped voices dominate; at others, the chorus intones the texts; the orchestra an ever-present commentator, its impressionistic harmonies fulfilling Adams? description of creating a "memory space" where each listener can find a personal response to the events. The orchestra erupts in an overwhelming climax after the words "I wanted to dig him out," managing, in a brief passage, to encompass anger, deep grief, and the enormity of the tragedy. Then it subsides into a long, slow decrescendo overlaid by the quiet recitation of names, as if the souls of the title hover over us. Adams has created music for his time and place that fulfills music's ability to move us. --Dan Davis Similar CDs

Similarly Requested CDs

|

CD ReviewsIncredibly, intensely moving; yet ultimately cathartic. Bob Zeidler | Charlton, MA United States | 09/18/2004 (5 out of 5 stars) "In reviewing "On the Transmigration of Souls," John Adams's Pulitzer Prize-winning memorial work to commemorate 9/11, I hope my (usually) reliable words don't fail me. For this is a difficult task, given the effect this work can have on one. It is an unusual work, psychically and spiritually moving almost beyond description, and I believe we all should be thankful that the commission for the work had been awarded to Adams, for I perceive no other composer - certainly no other American composer - as being even remotely up to the task set out. Adams succeeds on every possible level (despite his apparent initial concern that a suitable musical memorial was in fact possible). This is a work of universality, not polemical or political or jingoistic in the slightest. It is neither a requiem nor a kaddish but is in fact a true memorial to those who were lost, not only by Adams, but, through the texts used, by the people who suffered those losses. And, while it is a "public" piece, it is one of such "private" introspection that it seems to me that only through the recording medium - and then under the best of circumstances, such as the quietest possible background ambience or, better yet, listening with headphones - can its fullest impact be properly made, if only to establish that every single sound one hears in this work is intended to be there. (I had the opportunity to hear the concert performance of the work when it was webcast. I took a bye at the time, and I'm glad that I did. I feel as if, had I listened then, I would always be wondering whether I was actually listening to the work qua work or to the work under "live audience" conditions, with the distractions such conditions can produce.) "On the Transmigration of Souls" borrows somewhat from, or at least builds largely on the soundworld of, Charles Ives. This works on multiple levels, in both obvious and unobvious ways. There is some innate symbolism in how it mirrors the ambiguity of "The Unanswered Question" in a number of ways (including an intoned trumpet solo, performed to perfection here by Philip Smith, the NYPO principal trumpeter). In various places, the strings play simple diatonic harmonies, just as in TUQ. The nature of the work is, at its core, collage-like, again an Ives touchstone. And there is an unforced connection that may be made between this work and the final movement of Ives's Second Orchestral Set, Ives's spontaneous creative reaction to being in a New York crowd of people on the day that the Lusitania was sunk. But there are other touchstones familiar to those who know Adams's works well. His earlier masterpiece, "Harmonielehre," established a connection with the soundworlds of Sibelius, Mahler and Wagner, and it is to Sibelius that he seems to turn when, about 17 minutes into the work, a great brass peroration, as if to rise to the sky, punctuated by bold timpani strokes, leads into a massive choral outburst: "light...day...sky..." "On the Transmigration of Souls" opens with what sounds like normal street noise. But it is soon followed by readers softly intoning "Missing..." and an a capella choral entrance with only harp accompaniment. Then begins the reading of names, softly repeated across the sonic stage. Gradually the orchestra enters as the name reading continues. The solo trumpet intones the Ivesian touchstone, as if to suggest: "What IS the answer to this question?" The choral richness grows ever so slowly and subtly as the readings include not only names but personal reminiscences of the day - and the loved ones lost - that constituted 9/11. The orchestral music becomes more collage-like; fragments come seemingly from everywhere; harmony becomes more ambiguous and unstable. After eight minutes, the choral intonations become more minimalistic and repetitive, as if to match the readings of the speakers. At 10 minutes, one hears footfalls while further descriptions of the lost victims continue. A sinister tone on contrabassoon and double bass underpins the readings, and then the brass begin to lash out, with timpani strokes and percussion, mainly bells. At 12 minutes, the chorus begins to intone a more soothing incantation, with the children's choir, and then the adult chorus, singing the tributes and remembrances; once spoken, now sung. The choral outburst leads to a cacophony of bells and strings, gradually to subside, leading into, at the 17-minute mark, the Sibeliean brass peroration and then the bold massed choral entry. Ultimately the brasses struggle upward and downward simultaneously briefly, fading to (once again) enigmatic string fragments as the reading of the names resumes. Near the 21-minute mark, the harmonies settle into something less ambiguous; more identifiable, almost Mahlerian in their angst, then only to have the enigmatic string harmonies, now mainly in the tonic, return as if to once again and finally remind us of "The Unanswered Question." There is also an Ivesian transcendence to the final harmonic ambiguities, not unlike the closing bars of his 4th Symphony, just prior to the final fade-out, when the street noise is all that is faintly left. All of this takes place in just 25 minutes, and this is the only work on this Nonesuch "CD Single." We are left to contemplate the day, and the music - what Adams calls "a memory space" - in commemoration of the day. And that is as it should be. I have long been an admirer of Adams and his compositions. He long ago moved well beyond his initial characterization as a "minimalist," in conflation with Steve Reich, Philip Glass and Terry Riley, to become an "artist without stylistic borders." "On the Transmigration of Souls" is an unquestioned masterpiece; absolutely everything about it is "right": it hurts; it doesn't heal; it reminds us; and it must be heard. Bob Zeidler" A fine piece of the moment, yet a footprint in the ear Jeff Dunn | Alameda, California United States | 07/05/2005 (3 out of 5 stars) "John Adams' sensitivity to the subject and orchestration skills weigh mightily in this work, comparable in emotional scope to two earlier works, "Aria of the Falling Body" from the opera "Death of Klinghoffer" and "The Wound Dresser." The fine qualities above, however, are not enough in my opinion to make this a great MUSICAL work. Great theater with incidental music, yes. What seems to be lacking here is motivic and melodic content, elements that are the most likely to carry the work into future generations. I agree with the previous reviewer who commented that it was written too soon. The piece is expert reportage of the profound sadness of the moment, but what 9-11 will mean to us as a nation has not yet been played out. Note that Britten's masterpiece had the proper perspective 40+ years after the REAL disaster of the 20th century from which all others flowed, WW1. The upcoming "Dr. Atomic" by Adams may have that perspective, but from the excerpts I've heard so far, the music suffers from the same vacuity of memorability that may prove the undoing of "Transmigration." The words and the sonic environment carry this work, which I found temporarily moving, but I was left with a hole musically. Perhaps that's what Adams intended metaphorically as a World Trade Center footprint in the ear. Nevertheless, I am not a completely happy camper, especially for the full list price for only 25 minutes of music and a few nice tiny photos. In my book, the best music of this kind was composed by Joseph Schwantner, his "New Morning for the World" illustrating the words of Dr. Martin Luther King." Masterful Memoriam of Our Defining Moment Ed Uyeshima | San Francisco, CA USA | 10/08/2004 (5 out of 5 stars) "Realizing he is one of our most important and most played contemporary composers, I have to admit that in the past, I have run hot and cold on John Adams' music. At times, his work can be profoundly moving and emotionally stirring, but there are other times when his minimalist style can become obscure and droning. As it turns out, these opposing forces feed beautifully into this brief but elaborately arranged piece. In fact, Adams proves the ideal choice to produce this magnificent, multi-faceted work as he captures the range of feeling we all felt on 9/11 from abject horror to exhausted numbness. I'm sure there will be some who would have preferred something more Copland-esque, more messianic, more patriotically uplifting to commemorate the memory of that fateful day, but Adams uses his particularly atonal style to great effect producing a piece that is alternately spiritual and otherworldly. Adams is fully aware of the time that has elapsed, as well as the events and revelations that have moved us to opposing political factions. That's why his work feels like what he calls fittingly a "memory piece" since anything that tries to encompass our changed perspective on that day would be far too complex to embrace in a single work. What Adams does capture perfectly is how we remember the unmitigated feeling of violation and concurrently, the insecurity widely shared as to the immortal future of human beings. And he does it economically, clocking in at 25 minutes and conveying the basic message that we do not know where or when we are going.

In totally atypical fashion, Adams has assembled a text comprised of three main sources: brief fragments taken from missing person signs that had been posted by friends and family members in the immediate aftermath of the tragedy; personal reminiscences; and a randomly chosen list of names of the victims. The work also employs a "soundscape" designed in collaboration with engineer Mark Grey that surrounds the audience with pre-recorded city sounds (quiet traffic, voices, footsteps, etc.) and the reading by many different voices of the names of the victims. Conductor Lorin Maazel leads the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, expertly evoking the post-industrial sound that meshes perfectly with the text and sounds, as the drama of the music heightens at the right moments. The aural combination is startling and moving. For the best experience, I recommend listening to this alone with your thoughts and emotions. Adams accurately chose the term "transmigration" to describe his piece since he vividly guides the movement of souls from one state to another with his music and text. Suffice it to say that this is a work for the ages." |

Track Listings (1) - Disc #1

Track Listings (1) - Disc #1