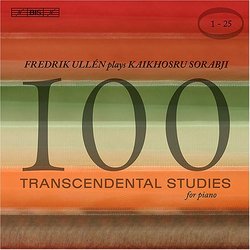

| All Artists: Kaikhosru Sorabji, Fredrik Ullén Title: Kaikhosru Sorabji: 100 Transcendental Studies, Nos. 1-25 Members Wishing: 3 Total Copies: 0 Label: Bis Original Release Date: 1/1/2006 Re-Release Date: 4/25/2006 Album Type: Import Genre: Classical Styles: Chamber Music, Forms & Genres, Etudes, Historical Periods, Classical (c.1770-1830) Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPCs: 675754891824, 7318590013731 |

Search - Kaikhosru Sorabji, Fredrik Ullén :: Kaikhosru Sorabji: 100 Transcendental Studies, Nos. 1-25

| Kaikhosru Sorabji, Fredrik Ullén Kaikhosru Sorabji: 100 Transcendental Studies, Nos. 1-25 Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsBeyond Virtuosity.... Douglas M. May | 09/03/2006 (5 out of 5 stars) "This is an astonishing performance. The Sorabji Transcendental Studies are indeed transcendent in their rhythmic and textural demands, far surpassing in difficulty anything by Alkan or Godowsky. If this seems like a preposterous claim, I would refer you to Mr. Ullen's website on which he thoughtfully reproduces some excerpts from the actual scores. And though they nearly overflow the boundaries of what is humanly possible on a Steinway, at no time does Mr. Ullen attempt to divert attention to himself at the expense of the music. Rather, his is a modest and austere climb to this summit of pianism. All difficulties have been solved, all paradoxes untangled; the final result is as unencumbered by self-conscious virtuosity as Glen Gould's Goldberg Variations. The music itself is magnificent and perhaps the perfect introduction to Sorabji because of each etude's compact size and dedication to specific aspects of piano technique. By imposing the limit of brevity on his baroque imagination, Sorabji arrived at some of his most magical inspirations. Those who are unfamiliar with Sorabji will find that he represents a most peculiar fusion of Busonian New Aesthetic with Szymanowskian orientalism and the all-over piano technique of Charles Ives. The music is, frankly, cerebral, but in a haunting and unique way. A listener who immerses himself in Sorabji will discover emergent patterns over time that will draw him back to the music, much as the intricate lines of Tchelitchew's interior landscapes will haunt an observant viewer. The early studies are frequently devoted to the exploration of specific intervals such as the fourth, fifth, and sixth, but do not sound labored or academic. They share some affinities with the Debussy etudes in this regard. Of the longer studies, I should mention # 10, with its cascades of bitonal arpeggios conjuring up an image of four satanic pianists performing Chopin's Winter Wind etude simultaneously, #14 with its infinite chains of arabesques and veiled pianissimo mystery, and #23, Dolcemente scorrevole, which grows by accretion into a massive, seemingly impossible contrapuntal texture that involves every register of the keyboard. I look forward to future installments of this series--Mr. Ullen has recorded all 100 studies, and some of the later specimens last upwards of 30 minutes. As usual with BIS, the piano sound is magnificent, close enough for overtones to make themselves heard, yet spacious enough to clarify the oversaturated conterpoint. I have no doubt that this is the most important piano recording I have heard in a long time. " Sorabji's Towering Transcendante Alscribji | Washington, D.C. | 05/08/2006 (5 out of 5 stars) "This first CD of Sorabji's 100 Transcendental Etudes contains 25 exquisite studies for the piano that are performed beautifully and effectively by Fredrik Ullen. For those who are fond of Sorabji's world of sound, its vastness and highly exotic ornamental figures of an Oriental nature, then look no further. These studies not only present some of the most daunting feats for the pianist, they are also musical and imaginative. The etudes evoke moods a la Sriabin (No. 4 Scriabinesco, No. 10, and No. 13) as well as the tranquil nocturnes that recall moods a la Gulistan and Le jardin parfume(No. 14, No. 18, and No. 20). The etudes are full of Sorabjian style writing: cascading triads, asynchrony, glittering sweeping passages, glissandi, chromatic filigree, ornate undulating lines in the left hand supporting meandering melodies in the right hand, four voices played simultaneoulsy and musically, accentuated rhythms, arabesque patterns, melodic lines hovering in the background and disappearing into oblivion, and ever-changing patterns and musical ideas; in short, a treasure trove of some of Sorabji's most successful and mature (and lengthy!) works for the piano. Fredrik Ullen has the technique to not only perform these etudes convincingly but also musically. Ullen captures Sorabji at his fiendish in a very pursuasive recording that is highly recommended." A Sorabjian jackpot Paul J. Kohler | UT | 05/23/2006 (5 out of 5 stars) "I've been studying the music of Sorabji off and on for some twelve years now, and I must say that upon hearing this CD, I felt I had found the "jackpot" of the Sorabji literature. Much of K.S.S.' music is difficult to appreciate on first hearing. It's difficult to get your brain wrapped around it. This music, however, immediately convinces the listener that its composer had a powerful gift, and a unique and fascinating imagination. Mr. Ullen is one of the supreme pronents of this type of music today, and this disc is well worth any price! Very highly recommended!"

|

Track Listings (25) - Disc #1

Track Listings (25) - Disc #1