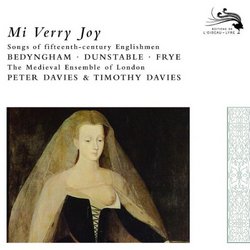

| All Artists: John Dunstable, Walter Frye, Johannes Bedyngham, Medieval Ensemble of London, Peter Davies, Timothy Davies, Paul Hillier, Patrizia Kwella, Rogers Covey-Crump, Paul Elliott Title: Mi Verry Joy Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Decca Import Release Date: 4/7/2008 Album Type: Import Genres: Pop, Classical Styles: Vocal Pop, Opera & Classical Vocal, Forms & Genres, Rondos, Symphonies Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPCs: 028947800231, 0028947800231 |

Search - John Dunstable, Walter Frye, Johannes Bedyngham :: Mi Verry Joy

CD Details |

CD ReviewsExquisite interpretations of 15th-century secular music Maddy Evil | London, UK | 02/19/2010 (5 out of 5 stars) "Twenty-five years after it was first released, this magnificent recording of 15th-century secular music has finally become available once again. Listening to it today, one wonders why Decca took so long to reissue it. The programme concentrates on English music from the period, featuring works by John Bedyngham (d.c.1460), John Dunstable (c.1390-1453) and Walter Frye (d.1475), and it includes 2 of the most famous works of the day: 'O rosa bella' and 'Mon seul plaisir' (sung here to the contemporary English text, 'Mi verry joy'). The line-up includes some of the best known performers specialising in medieval music, several of whom also forged their careers in groups such as Gothic Voices and the Hilliard Ensemble. 'Le serviteur' (track 3), 'Puisque m'amour' (track 8) and 'Je languis' (track 9) are just three of the many examples of mellifluous and achingly beautiful singing which can be found in abundance here. Only one other recording of similar repertory perhaps surpasses this outstanding release - namely The Castle of Fair Welcome, performed by Gothic Voices (Hyperion 66194, recently reissued as Helios 55274).

As the renowned musicologist David Fallows explains in his informative liner notes, this recording was originally released at a crucial time (in 1983), since leading musicologists were just coming to the consensus that 15th-century song was almost certainly intended for voices alone. The impact of this cutting-edge research on Peter and Timothy Davies (the joint directors of the Medieval Ensemble of London) is immediately apparent upon comparing 'My Verry Joy' with some of their earlier recordings, where instruments had featured prominently (e.g. Ce Diabolic Chant: Ballades, Rondeaus & Virelais of the late fourteenth century [Decca "L'Oiseau-Lyre" 475 9119]). Two-thirds of the present CD is "a cappella", and of the 5 remaining tracks where an instrument is actually used, 4 feature just 1 lute alongside 2 singers (tracks 4, 11, 12 and 15). Indeed, the only track where 2 instrumentalists are present (playing vielle and lute) is the instrumental rendition of the two-part ballade 'Watlin Frew' (track 13), which, in any case, is actually preserved without text in the one extant source which transmits it (the Strahov manuscript [D.G.IV.47, fol. 245v] - incidentally, since the liner notes do not mention it, the strange title 'Watlin Frew' is thought to be a corruption of Walter Frye's name). Nevertheless, is it really fair to claim, as Fallows does, that the instrumental participation on this recording - i.e. 1 lute - is "disturbing...[making] the music more confused and less eloquent" (liner notes, p.4)...? Even aside from the fact that this dismissal seems an unduly harsh assessment of tracks like the exquisite rendition of 'Tout a par moy' (track 15 - which amazon incorrectly lists as being from the Buxheimer Orgelbuch), Fallows's comment is curious on two fronts. Firstly, he is much kinder in liner notes for recordings by other groups which are considerably more dubious, academically speaking (e.g. Ensemble Gilles Binchois's instrument-dominated recording of secular music by Binchois, entitled Binchois: Mon souverain desir - Chansons /Ensemble Gilles Binchois * Vellard [Virgin Veritas 7243 5 45 285 2], etc.). Secondly, whilst the case for all-vocal performance of this repertory is clearly extremely persuasive, both aesthetically and musicologically, it seems treacherous to claim that there is "no evidence for performing the secular song repertory from before 1480 with instrumental accompaniment" (liner notes, p.4). Potentially problematic sources for this assertion include - 1) eye-witness descriptions, such as the well-known account of 2 singers & 1 lutenist who performed at the famous 'banquet du voeu' in 1454 ("...et au pasté fut joué dung leuz avecques deux bonnes voix...", 'Memoires' of Olivier de la Marche); 2) evidence that churchmen of the period - i.e. the main composers and performers of polyphonic music - sometimes owned instruments (such as the canon Ernoul de Halle at Cambrai, who left a harp, lute, gittern, rebec, psaltery and 2 vielles at his death); and 3) visual and iconographical representations of small mixed ensembles featuring voices and soft instruments. Whilst it is certainly true that such "evidence" is not specific enough to support today's widespread assumption that 15th-century song definitely (and regularly) had instrumental accompaniment - i.e. it may simply relate to performances of semi-improvised polyphony/monophonic music (like that preserved in the Bayeux manuscript, BNF 9346) - the obverse is equally true: namely, can we really be 100% certain that NOT ONE of these sources relates to the performance of polyphonic music...? In short, the best compromise for modern listeners is probably to assume that 15th-century song was most often performed by unaccompanied voices, but that participation of certain instruments (particularly harp and lute) may occasionally have occurred. These 2 possibilities are presented most persuasively on this release. Sadly, 'Mi Verry Joy' was one of the very last recordings issued by the Medieval Ensemble of London. Judged on the strength of this release, the loss of so fine a group interpreting this repertoire is regrettable indeed. " |