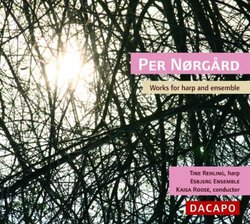

| All Artists: Per Norgard, Kaisa Roose, Esbjerg Ensemble Title: Per N�rg�rd: Works for Harp and Ensemble Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Marco Polo Original Release Date: 1/1/2006 Re-Release Date: 4/18/2006 Genre: Classical Styles: Chamber Music, Forms & Genres, Concertos, Historical Periods, Classical (c.1770-1830), Instruments, Strings Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 636943603925 |

Search - Per Norgard, Kaisa Roose, Esbjerg Ensemble :: Per N�rg�rd: Works for Harp and Ensemble

| Per Norgard, Kaisa Roose, Esbjerg Ensemble Per N�rg�rd: Works for Harp and Ensemble Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsHarp pieces from several different eras of this tremendously Christopher Culver | 09/04/2006 (5 out of 5 stars) "Da Capo has issued several beautifully packaged and well-programmed collections of Per Norgard's music lately, and this one highlights the great Danish composer's writing for the harp. Tine Rehling is the soloist, and she is occasionally accompanied by the Esbjerg Ensemble conducted Kaisa Roose. Everything sounds superb, I've heard few recordings with such clarity as here. The first work here is one of Norgard's most supremely beautiful. "Through Thorns" (2003), a small concerto for harp and flute, clarinet, and string quartet, looks back to Norgard's explorations of hierarchal music of the 1970s. In that time, the composer was discovering the possibilities of the "infinity series", a fractal-like method of generating melody, harmony, and rhythm where all components of a work are integrated into an awesome whole. For an introduction to this technique, one should seek out the Symphony No. 3, the composer's masterpiece (it's available on Chandos in an excellent performance), where *everything* is derived from the infinity series. Norgard put overt uses of the series aside to concentrate on other matters, such as schizoid writing and rhythmic and tempo experiments. Towards the end of the 1990s, however, Norgard thought that there were still new uses of the infinity series. One such new use is found here, picking and choosing notes from the infinity series instead of playing all notes from the series at a time. One would think that the result would be almost random, but everything still seems so marvellously connected. At the concerto's heart is a little melody Norgard wrote almost thirty years previously for a Marian hymn and then used in several other pieces, "Flos ut rosa floruit". The harp enters alone, feminine and elegaic, before being surrounded by other instruments. The harp then seems to have to move around the ensemble, sometimes taking small cautious steps, sometimes fleeing. The direction the work took reminded Norgard of another Marian hymn, "Through thorns the Virgin goes", which inspired the title. And the last lines of this second hymn, "And roses blossomed among the thorns", are put into music in the great reconciliation of the harp and ensemble at the end of the piece. Two works for solo harp were written at around the same time as the concerto. The first is "Consolazione: Flos ut rosa" (2002), which is more simply based on Norgard's old melody. The other "satellite work" of the concerto is the two-minute "Notes falling. Spring sun with freckles" (2004). Quite hermetic, this and the composer's tenth string quartet of the same period are among the most intensely personal pieces of a composer whose work has usually shown a cosmic outlook. The remaining works on the disc are from earlier periods of Norgard's career. The four-movement "Sonora" for flute and harp (1981) dates from the great change in Norgard's music at the beginning of the 1980s, when the infinity series gave way to a schizoid style inspired by the mad Swiss artist Adolf Wolfli. Like in other works from this period, there are shifts between idyll and catastrophe. The soft outer movements are nearly identical, but in the intense two inner movements mourning can be replaced in an instant by a happy dance, and sweet lilting by abrasive tones. "Lilttle Dance" for harp solo (1982), on the other hand, possesses another trait of the Wolfli period, child-like simplicity. Two works here date from the end of the 1980s, when Norgard was working on his enigmatic Symphony No. 5 where his interest seemed to be mixing many different strains into the same musical fabric and seeing how well the ear can distinguish them. "King, Queen, and Ace" (1989), a concertino for harp and thirteen instruments, has two very different opening movements, and a third that reconciles them by interweaving elements of both. The King movement, a "prelude and march", is haughty and sure of itself, with percussion full of pomp and glissandi on the harp. The following Queen movement, a "prelude and song", is subdued and full of doubt, with pointilistic writing and a meandering flow. In the final movement Ace, we get a "prelude and waltz". How it combines the King and Queen is difficult to put in words, but makes for splendid listening. Norgard says that the Ace possesses both absolute superiority and innocence. The music is generally soft, hymn-like but with the occasional outbursts. In a way, the Ace seems the real beginning of the piece, and the King and Queen only excepts from it. This concertino has been recorded before, by Joanna Kozielska and the Arhus Sinfonietta conducted by Soeren K. Hansen on Kontrapunkt, but both performances have their strengths and I can't say I favour one over the other. The other work from this period is "Swan Descending" (1989), essentially a brief series of variations. It is a lush and appealing work, probably the most simply beautiful one here after "Through Thorns". The first thing that strikes one upon hearing "Hedda Gabbler" for viola, harp, and piano (1993) is its rhythmic complexity. These seventeen little movements, written as incidental music for a BBC production of Ibsen's play, occasionally approach Elliott Carter in their explorations of tempo, and foretell Norgard's piano concerto "Concerto in due tempi" written the following year. But are movements are so frenetic, we find brief bits in the vein of the Baroque period, waltzes, and even a 13-second nocturne in F major inspired by Chopin. The best introduction to Norgard's music are probably any of the symphonies on Chandos. The Third is his most popular, while the Sixth is a cauldron of many bubbling ideas for fans of unabashed modernism. Still, Norgard is one of the most inventive composers of our time--that he is so little-known among listeners of contemporary repertoire is simply criminal--and all of his music is worth getting." A Very Great Composer Giordano Bruno | Wherever I am, I am. | 07/17/2008 (5 out of 5 stars) "It's time, friends, to call your attention to Per Norgard (b. 1932), one of the constellation of great contemporary composers from Scandinavia. Just guesswork on my part, but I suspect that music-lovers who aren't certain of their response to ultra-modern music will be at least partly persuaded by Norgard's music for harp and harp-centered ensembles.

On a grandiose level of generality, I offer the notion that music can be divided into two classes: 1) music based on memory, on the ability to hear a melody or a theme and enjoy a structure of time; European music has excelled in this category, the ultimate form of which is polyphony; 2) music based on acoustic delight, pure sound as it occurs in the moment of hearing; gamelon and gagaku are examples; modern Euroamerican and Japanese composers have explored this category brilliantly. What makes Norgard special is that he balances the two ways of composing more effectively than almost anybody. Norgard is clearly an innovative structuralist, using what he has called an "infinity series" to shape his compositions through the time-scape of hearing them. (Don't worry about it! It's not so scary! You don't need to understand music theory to hear Norgard's exciting musical phrases.) At the same time, Norgard is clearly delighted by sounds as such, and it's his rainbow of sound colors that will first impress most listeners. What's he doing? Well, a lot of fractional pitches, glissandos, unexpected overtones and wolf-tones, occasional modal tunings, etc., but not merely on a try-and-see basis; he knows what he wants. These harp-ensemble pieces call on the performers to use "extended techniques," and Norgard proves that he fully grasps the possibilities of the different instruments for such extensions. The flute and clarinet players need to master flutter tonguing, overblowing and underblowing, and "soft" semi-closing of the keys. The string players use bridge tones, sliding fingers on the finger board, and bowing techniques not needed for classical compositions. The harp - that simplest of instruments in concept, a set of tuned strings plucked one by one - sounds unlike any wedding-prelude harp music you've ever heard; Norgard's harp would suite Beowulf better than Tschaikowsky. Much of the sound color results from the mathematical anomalies - acoustic interference patterns - that result from unstopped vibrating strings with certain pitch relations. In other words, two notes played together or overlapping on a harp often produce a sound that's more than the sum of the two notes. Norgard sets the results of these extended techniques in thrilling combinations and juxtapositions. On first listening, this acoustical magic will be what one hears most. Only a few more listenings will reveal the larger temporal structure of the music. Without masterful performance, this music simply wouldn't exist. This performance by harper Tine Rehling and the Esbjerg Ensemble is masterful. " |

Track Listings (29) - Disc #1

Track Listings (29) - Disc #1