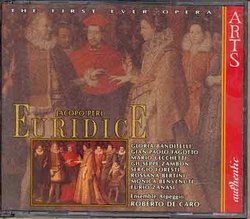

| All Artists: Sergio Foresti, Rossana Bertini, Monica Benvenuti, Furio Zanasi, Paolo Da Col Title: Peri - Euridice / Banditelli · Fagotto · Cecchetti · Zambon · Foresti · Bertini · Benvenuti · Zanasi · Ensemble Arpeggio · de Caro Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Arts Music Release Date: 6/18/1996 Genre: Classical Styles: Opera & Classical Vocal, Historical Periods, Baroque (c.1600-1750) Number of Discs: 2 SwapaCD Credits: 2 UPC: 600554727622 |

Search - Sergio Foresti, Rossana Bertini, Monica Benvenuti :: Peri - Euridice / Banditelli · Fagotto · Cecchetti · Zambon · Foresti · Bertini · Benvenuti · Zanasi · Ensemble Arpeggio · de Caro

| Sergio Foresti, Rossana Bertini, Monica Benvenuti Peri - Euridice / Banditelli · Fagotto · Cecchetti · Zambon · Foresti · Bertini · Benvenuti · Zanasi · Ensemble Arpeggio · de Caro Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsThe first complete opera to have survived in a fine recordin Craig Matteson | Ann Arbor, MI | 11/01/2005 (5 out of 5 stars) "Opera grew out of the court festivals of late sixteenth century Italy. The nobles were quite interested in all the arts and employed skilled painters, sculptors, poets, and musicians. There was also a great deal of interest in reviving all things Greek because they were seen as the ideal model for all things intellectual. Reviving Greek music involved a great deal of conjecture and imagination because only a few fragments of their music survive and it is by no means agreed upon, even to this day, what they actually mean. One of the groups of Florentine intellectuals surrounded a Count Bardi, which he called the Camerata. They wrote letters to each other, so we have some idea of their thoughts about what it was they were trying to do. They called what they did the "New Music" or the "Second Practice" and music students learn to call this style monody (solo voice with simple accompaniment). It caused quite a furor among those who were proponents of the older style of counterpoint. One of those who opposed Monteverdi was a fellow named Artusi. Every music student reads his articles against those composers with "smoke in their heads". And of course, Artusi always comes out on the wrong side of history and made to look the fool. However, the art of these composers was shocking and their free use of dissonance compared to the rules of Zarlino and the practice of Palestrina, Ockeghem, Josquin, and others is jarring. However, we have a hard time hearing the difference in these musical styles unless you pay close attention and develop some familiarity with what the argument was all about. Some of these Second Practice composers came to believe that the Greeks sang their plays from beginning to end. This is almost certainly not true, but the point was they believed it. Composers such as Caccini, Peri, and Monteverdi developed a style of solo singing they felt captured this idea and called it the "stile rappresentativo" (the representative style). It is this recitative style that Caccini and Peri used in developing their art. When you listen to Peri's "Euridice" you will notice that most of it is a very expressive version of what we would call recitative - the almost spoken parts between the arias - and that the aria as even Monteverdi developed it a few years later is almost nonexistent. If you understand that they were trying to recapture the Greek storytelling that they believe was a sung style, this makes a great deal of sense. In fact, this kind of work was not called "opera" until the mid-seventeenth century (opera simply means "work" as in a work of art). Before that term came into general use, the composers referred to their works as musical fables or music dramas. However, our referring to all of it as opera makes sense given the genealogy of the art form. Peri's "Euridice" is the first surviving opera we have in complete form. His "Dafne" came first, but is now lost. Caccini was a court rival and was working on his own version of "Euridice" and at the first performance there was apparently a mix of the two composer's works. But the nod is given to Peri and Caccini published his own version, but he completed his version later. It is interesting the Monteverdi also did a version of this myth, but called his "Orfeo". This is a beautiful recording of this work. It is important to know that even though the complete opera in printed form survives, there is a great deal that is not in the score. A great deal of scholarship and artistic sensitivity has to go into recreating a version of this opera that both succeeds musically and has some claim of authenticity to Peri's intentions for performance. You will also note the vocal style has nothing to do with Verdi or Wagner. This was for a much smaller hall with only a few hundred of the nobility present. And while it was first performed for a wedding festival and did not please those for whom it was written, it began a four hundred year development of an art form that millions adore and consider to be one of mankind's great achievements. I am one of them. Enjoy! There is a very helpful booklet with these disks to help you understand the history and the libretto is provided in English and Italian." Complete opera at mid-price Giordano Bruno | 03/18/1999 (4 out of 5 stars) "As Peri's Dafne of 1598 is largely lost this work of 1600 counts as "the first ever opera" (CD Box). With Gloria Banditelli as Euridice obviously this is a subtantial release for lovers of early opera. Recorded in Bologna in 1992. Full libretto and English translation. Total time 101'40." Off to a Flying Start! Giordano Bruno | Wherever I am, I am. | 10/22/2008 (5 out of 5 stars) "In the last half of the 16th Century, a small circle of friends and rivals in Florence - a city not as populous as Lubbock, Texas, today - invented the modern world. Known to historians as "humanists," their names are not all familiar: Giovanni de'Bardi, Cristofano Malvezzi, Giulio Caccini, Ottavio Rinuccini, Emilio de'Cavalieri. The most famous name will be that of Vincenzo Galileo - the lutenist and theorist of music, not his slightly disreputable son Galileo Galilei - whose efforts to rediscover the forms and techniques of ancient Greek music were intimately connected to the efforts of others to recreate classic Greek drama. The conversations and printed debates of this tight circle of Neo-Platonists, all of them polymaths, focused on the nature of emotions, the relationship between art, especially music, the expression of emotions, and the whole broad question of human nature per se. Remember the credo? "The proper study of mankind is man." When I declare that the humanists of Florence, and of Northern Italy at large, invented the modern world, I'm not entirely engaging in hyperbole; the scientific method, the secular society, and modern sensibilities from classicism to romanticism to expressionism were all born in the ardent discussions of these brilliant few.

Most of the humanists had at least some musical training. A large part of their prominence depended on the patronage of the Medicis and other secular lords, and they were expected to entertain and instruct, through their conversation and through the staging of public entertainments, particularly those associated with the affairs of the Medici family. Medici weddings were for Florence what the Inaugurations of Presidents and the Olympics, with Mardi Gras thrown in, are for our times. Much of our knowledge of music, dance, drama, and pageantry comes to us from the "scripts" of Medici weddings, like that of 1589. One of the leading musical humanists of Florence was Jacopo Peri (1561-1633). To Peri, after the usual intrigues between rivals, fell the task of composing music for the "pastoral drama" Euridice, written by his friend Ottavio Rinuccini. The goal, as elaborated by the discussions of 25 years, was affective expression of the text -- intelligible recitation of poetry somehow set to music. Peri didn't pull 'recitativo' out of his hat like a rabbit, however. The Florentines had been used to the insertion of musical show-pieces - skits called intermedii - between the acts of stage plays and public pageants. Perhaps an even more important precedent existed in the art of poets who accompanied themselves on the lyra da braccio. This is one of the great mysterious lost components of Renaissance music. We know what the lyra da braccio looked like, but we have no idea how it sounded. The repertoires of those who played it and sang their poems were closely guarded and never written down. It was supposedly all improvised. Such musician/poets were among the most highly paid artists of the era. My guess is that Peri, Monteverdi, and the others who developed accompanied recitativo, in the context of madrigal-settings of Petrarch, Tasso, and Guarini, were essentially formalizing an existing performance tradition. Peri's 'Euridice' was performed in a salon on the upper floor of the Pitti Palace in 1600, for an audience of about 200 invited guests, in honor of the wedding of Maria dei' Medici to Henri IV of France. Nothing is known about the sorts of instruments played for the dances in the opera or for the basso continuo. Another composer, Giulio Caccini, politicked the inclusion of his music instead of Peri's in the concluding scene, and rushed his full score into print before Peri could publish. It was a fairly short work, roughly an hour and a quarter, and it included brief polyphonic choruses and dances as well as extended recitativo. Members of the audience were almost certainly unaware of the explosion of musical innovations that would follow this somewhat botched premiere. In terms of affective expression of emotion, Peri got it right the first time. The story of Orpheus and Euridice was then and is now known to everyone, although the ending of Rinuccini's libretto differs from most accounts. Perhaps a wedding celebration mandated a happy ending; the lovers are reunited and the nymphs and shepherds celebrate. The recitativo is amazingly eloquent and imaginative throughout, and the brief interruptions of song and dance are just piquant enough to give all that emotionalism zest. The first opera, in short, was first rate! This is a first rate recording also. The singers are all Italian, so their diction is clear enough to understand if you speak Italian, or to follow in the printed libretto included with the CD. Tenors Gian Paolo Fagotto and Marco Cecchetti sing the largest roles, as Orfeo and his friend Aminta, and they are extremely musical in their delivery of the recitativo. Countertenor Giuseppe Zambon is stunning in the smaller role of the shepherd Arcetro; I'll be watching for his name on other CDs. Soprano Gloria Banditelli sings four roles - Euridice, Tragedy as a prologue, Proserpina, and a Nymph - and makes all of them distinct in expressiveness. The ritornelli are performed on recorders, a appropriately pastoral sound. The continuo is richly varied, including theorbo, guitar, lute, harp, spinet, and lyre - all plucked strings - plus gamba, violone, and organ. The plucked strings are the epitome of elegance. I doubt that this work could be staged effectively in a large or even a medium-sized opera house. It's a chamber opera, and as such it can be enjoyed fully, I find, just be hearing it on CDs. It's more than a curiosity, this first opera. It's an exciting counterpart to the madrigals of Monteverdi, Rossi, and d'India, written at the same transcendent moment of cultural history." |

Track Listings (22) - Disc #1

Track Listings (22) - Disc #1