| All Artists: Philippe Graffin Title: in the shade of forests Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Avie Original Release Date: 5/24/2005 Release Date: 5/24/2005 Album Type: Import Genres: New Age, Pop, Classical Styles: Instrumental, Vocal Pop, Opera & Classical Vocal, Chamber Music, Historical Periods, Classical (c.1770-1830), Instruments, Strings Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 822252205923 |

Search - Philippe Graffin :: in the shade of forests

CD Details |

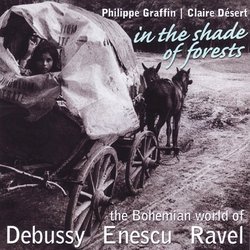

CD ReviewsThere are better choices for Enescu and Ravel - even with th Discophage | France | 04/13/2008 (3 out of 5 stars) "Enescu's "Impressions d'Enfance" (Impressions from Childhood) is an incomprehensibly neglected and under-recorded masterpiece of the 20th-Century repertoire for Violin and Piano, equal in stature to the composer's Third Sonata. Composed in 1940 and first performed by Enescu himself and Dinu Lipatti at the piano, it is a nostalgic and comforting reflection of the ageing composer on his childhood, and especially a conjuration of his memories from the famous Gipsy fiddler Nicolas Chioru. A suite of 10 pieces playing without break, with evocative titles - ""The Strolling Fiddler", The Old Beggar", "Brooklet at the Far End of the Garden", "Bird in Cage and Cuckoo Clock on the Wall", Lullaby", "Cricket", "Moon through the Window Panes", "Wind in the Fireplace", "Storm Outside, in the Night", "Rising Sun" -, it is a journey through late afternoon, evening and night, ending with the rising morning sun in an exultant D major. The music is descriptive, but it is much more than that: Enesco uses a wide array of incredible Gipsy-inspired violin effects, trills, sul ponticello and ricochet bowing, harmonics, ornate melismatas, while the piano part is thick and showered with grace notes, glissandos and arpeggios, giving it a very "aquatic" texture. Graffin and Désert contribute a good reading (with a fine spirit of exultation in the final movement) but, on close comparison, they are simply not in the same league as Kavakos on ECM (Ravel: Sonate posthume; Tzigane; Enescu: Impressions d'enfance; Sonata No. 3) and Kremer on Teldec (Enescu: Impressions d'Enfance; Schulhoff, Bartok: Violin Sonatas). And then, there is also Patrick Bismuth, who like Kavakos also features Enescu's magnificent 3rd Sonata, but errs a little too much over the top of wild expression (Violin Sonata; Ravel: Tzigane) - although, for reasons stated hereunder, his version is in more direct competition with Graffin than either Kavakos and Kremer. In comparison to these interpretations, Graffin seems earthbound. His "bird in the cage" chirrups frenetically - an understandable psychological condition for the poor sparrow, but the unfathomable sadness Kavakos lends it is much more moving, and the same kind of nostalgia imbues his "Old Beggar". In the "Cricket" Graffin dutifully plays "saltando" as Enescu instructs. Kavakos and Kremer add to that an incredible pinched sound, imparting it superior color and character. Bizarrely, Graffin gives the grace notes of "Moon through the Windowpane" equal value with the main pitches, robbing the melodic line of its contour. His "sul ponticello" in the "Wind in the Fireplace" is almost pretty - no match to the eerie and terrifying sounds Kremer pulls out of his fiddle. These are only a few examples, and again, Graffin is fine, but with a measure of exaggeration, I'd say that with him you hear the notes, the beat, the bar, while with Kavakos and Kremer you hear the music - more still: you are penetrated with the impressions. Graffin and Désert might have scored in their adoption of the Luthéal rather than the piano in Ravel's Tzigane. The Luthéal, invented by the Belgian George Clootens in the early 1920s, is a mechanism fitted to a concert piano that makes it possible to add three registers to its normal one, imitating the cymbalum, the harpsichord and something called by the inventor "harpe tirée" (pulled harp), which sounds very much like Cage's prepared piano. The Luthéal soon fell out of fashion, as its mechanism was too sensitive and needed constant adjustment. Though the notes are unclear about this, Tzigane was indeed originally conceived for the instrument, and according to the notes the score contains detailed instructions for register changes - although not all versions seem to use the same registration options. Anyway, it adds much to the Gipsy color of the piece. Désert plays the actual Clootens-adapted Pleyel piano, kept at the Brussels Museum of Music Instruments. There are two other versions Tzigane with Luthéal that I am aware, one by Patrick Bismuth, which comes as a filler to the Enescu disc mentioned above, and the other by Daniel Hope (East Meets West), and both are better than Graffin's. Ironically, Graffin plays his Ravel like Bismuth played his Enescu (while Bismuth is exceptional for his precise observance of Ravel's marks). In the introductory cadenza Graffin seems to think that giving a Gipsy characters requires constant coaxing of the lines, and he fiddles so much with Ravel's notated rhythms that he threatens to loose any sense of a steady pulse. The sonics also pick up his heavy breathing. Things get better with the entrance of the Luthéal and Graffin's expression is idiomatic, but both Bismuth and Hope observe more precisely Ravel's articulation marks, and there are spots where, either by interpretive choice or because of digital limitations, I felt that Graffin was slightly bogged down in tempo. Ravel's early Sonata, a student piece composed in 1897 and rediscovered in 1975, comes as a welcome bonus. It shows the influence of Fauré and early Debussy. On the other hand Graffin contributes an excellent Debussy Sonata, one of the broadest I have heard in the first movement (but he is there in good company, with David Oistrakh), sometimes at the limit of acceptable freedom of rubato, but always with fine control of agogics and tempo flexibility. He also pays minute attention to Debussy's marks of articulation and dynamics, and he is the only fiddler I've heard on disc to differentiate his phrasing of the two upward leaps that open the second movement, and the two that follow eight bars later - indeed Debussy didn't write them staccato the second time. The additional Debussy trifles include transcriptions made by the American violinist Arthur Hartmann, who befriended the composer in 1908, while the short (4:10) "Nocturne & Scherzo" is the reconstruction by Graffin of an early piece for violin and piano (1882) which Debussy is recorded to having performed, but whose manuscript remains in the form of a near-contemporary transcription for cello. None of these Debussy trifles is indispensable, but they make for a well-filled (73'), yet ultimately not entirely satisfying disc. Good and informative liner notes. " Magnificent Jorge Strunz | Woodland Hills, CA | 05/06/2006 (5 out of 5 stars) "One of the best CDs we own. Terrific selection of material, exquisite renderings by sensitive masters. The Debussy Sonate Pour Violon et Piano is particularly gorgeous, the last complete thing he wrote. The expression here and everywhere on the disc is awe-inspiring. Flawless. It's hard to find words for such beauty. Graffin is the perfect combination of perfection and invention, replete with the most masterful technique and expressive dynamics, and Desert is magical -- their synergy is unmatched. I wish they would come to Los Angeles to perform! I would be first in line." Hauntingly intimate, delicate and beautiful A music fan | Teaneck, NJ | 12/02/2005 (5 out of 5 stars) "The image in front of the cover shows all the haunting beauty and delicacies that render this recording a first chioce over so many others.

I don't want to lose too words here, other than, if you buy this, you will not be disappointed. Graffin and Desert do a splendid job in bringing us the sadness and tragic of the gypsy life close to our ears. Wonderful and unique. Especially listen to the Lutheal in ravel's "Tzigane"" |