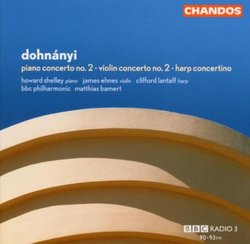

| All Artists: Ernst von Dohnanyi, Matthias Bamert, BBC Philharmonic Orchestra, Howard Shelley Title: Piano Concerto No. 2 - Violin Concerto No. 2 - Harp Concertino Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Chandos Release Date: 10/19/2004 Genre: Classical Styles: Chamber Music, Forms & Genres, Concertos, Historical Periods, Classical (c.1770-1830), Instruments, Keyboard, Strings Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 095115124529 |

Search - Ernst von Dohnanyi, Matthias Bamert, BBC Philharmonic Orchestra :: Piano Concerto No. 2 - Violin Concerto No. 2 - Harp Concertino

| Ernst von Dohnanyi, Matthias Bamert, BBC Philharmonic Orchestra Piano Concerto No. 2 - Violin Concerto No. 2 - Harp Concertino Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsGiving Dohn�nyi a Fair Shake Rumbachulo | Ithaca, NY USA | 11/12/2004 (3 out of 5 stars) "Fans of James Ehnes' full-throated, cultivated sound will not be disappointed by his clean and sophisticated interpretation of the Second Violin Concerto. As with his recordings of the Max Bruch Second Violin Concerto and Scottish Fantasy (CBC B000079B71), much of Ehnes' playing is well suited for this work that has a post-Brahmsian sound reminiscent of Korngold. For as much burnish and focus as Ehnes presses into his interpretation of the melodically languid sections of the concerto, he demonstrates his trademark assuredness of both hand and bow in faster technical passages. But with that said, I found myself wondering if there weren't some middle ground that had gone unexamined by Ehnes between the two.

The Intermezzo second movement of the Second Violin Concerto, marked Allegro comodo e scherzando, is most certainly "comodo," but seems to lack the sarcasm implied by the marking "scherzando." Even a Brahmsian scherzando should contain some wit and vigor. If Dohnányi's piano works indicate the possibilities for his chamber or orchestral works, it is their combination of near-abandon with a refined intellectualism reminiscent of the preceding Romantic period that is missing from Ehnes' reading. It lacks edginess and spiky crests of sound that provide sharp contrasts in the work that would set it off and make some of the darker passages memorable. "Joy" and "resolve" seem to be traded in for "accuracy" and "care" as Ehnes rounds the final Alegro risoluto e giocoso to a rather risk-free conclusion that seems antithetical to the Brahmsian quotation set by the robust architectural scaffolding of the piece. It is something vivid in color, something wild waiting to burst forth in this concerto that the listener waits for, but that Ehnes tames away before bring it forward. It as if he has forgotten that it is the lion's roar and snarl that rivets our eyes to the ring, makes the presence of danger apparent, and elucidates the skill of the man in the ring. Without it listeners perform an act analogous to the viewer's scan of the room, and they tune in and tune out particularly in rhapsodic works. Ehnes' approach, with its cautious aristocratic calculations, might have been better suited for a work like the Concertino for Harp and Chamber Orchestra. The Concertino for Harp and Chamber Orchestra is a very finely latticed work that is well served in this reading by harpist Clifford Lantaff. Lantaff's efforts clearly integrate the intellectual essay of this work with its own caprice with the works of early 20th c. French composers. Lantaff soars above, around and within the small ensemble with a great deal of dexterity as well as he becomes apart of the inner workings of the work. His tone production ranges from the icy and shrill to the warm and sonorous as he brings the concertino to its quiet cool, and convincing conclusion. However, it is Howard Shelly's reading of the Second Piano Concerto opus 42 that I've been waiting for ever since I first became familiar with the work. It is a demanding, neo-Romantic composition, comprised of fistfuls of glistening exaltations and thunderous chords from the piano. The quiet sections of the work are dark, cerebral meditations on the thematic material surround them rather than the song-like cantabiles of so many of its Romantic predecessors. It is a neo-Romantic work that is unique in that it requires a pianist completely familiar with the late 19th century piano concerto, but who is willing to look at the work as more than a quotation or a pastiche of the genre. I believe hat this work has been frequently overlooked because, unlike this recording that Shelly has given us, previous recorded performances have only examined the ways in which this concerto borrows from Brahmsian invention. Shelly's reading is indicative of an understanding of Dohnányi's nods toward neo-Classicism as well as his reaction to Bartok's use of variation. But more importantly, in this recording is evidence of Shelly's talent for reinventing himself and molding his sound and technique for the work. He is one of the few pianists of late who proves time and again that he is able to both serve the composer and make a declarative statement of self. Shelly's reading of this piece unifies its disparate sections in and makes connections between the separate sections of this piece with a signature affinity for both drama and accuracy. Shelly achieves both the thunderous as well as the deadly quiet through a widely colored pallet of sound that ranges from an ice blue to a burnt ember. At the end of this performance, the listener should be convinced that she or he knows as much about Dohnányi's concerto as what Shelly has to say about it. Had, however, someone told me that three different conductors had been employed for this project I would have been thoroughly convinced. Matthias Bamert must be a very forceful presence on the podium, because he seems to have an uncanny chameleon-like ability to fold himself and the orchestra into the soloist. Ehnes, Lantaff and Shelly push set paces, tones, and interpretive leads that Bamert follows. But at the end of each recording, we know less about what he has to say, and more about his effective ability to accompany. Although somewhat uneven, this recording is a very worthwhile purchase if only to hear consummate artists perform these rarely heard works. As always the Chandos sound is clear, well engineered, and immaculate in such a way that is helping us further define the differences between listening in the concert hall and recorded listening. The overall "thingness" of the CD is good, though, as always with Chandos the liner notes are lacking in any worthwhile, concrete information. Chandos seems to be under the impression that if we are told that certain works are "Hungarian-flavored" or "beautiful" that we will have collective understanding of what these things are. Chandos, however, is to be celebrated for giving these works over to artists who are up to the technical musical challenges. For the handful of recordings of the Violin Concerto no.2 and the Piano Concerto no.2, I believe that this is the first in which both the quality of the recording and the performances allow listeners a fair and precise opportunity to hear these works. " |

Track Listings (10) - Disc #1

Track Listings (10) - Disc #1