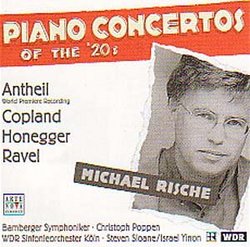

| All Artists: George Antheil, Aaron Copland, Arthur Honegger, Maurice Ravel, Christoph Poppen, Steven Sloane, Israel Yinon, Bamberg Symphony Chorus, WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln, WDR Sinfonie Orchester Köln, Michael Rische Title: Piano Concertos of the Twenties Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Arte Nova Records Release Date: 10/29/2002 Genre: Classical Styles: Chamber Music, Forms & Genres, Concertos, Historical Periods, Classical (c.1770-1830), Instruments, Keyboard Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 743219101426 |

Search - George Antheil, Aaron Copland, Arthur Honegger :: Piano Concertos of the Twenties

| George Antheil, Aaron Copland, Arthur Honegger Piano Concertos of the Twenties Genre: Classical |

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsAn enjoyable collection, with Antheil's brilliant and colorf Discophage | France | 03/13/2007 (5 out of 5 stars) "The career of George Antheil is a fascinating and depressing case of "What went wrong?" Here you have, in the 1920s, a brilliant young composer vying for fame, and writing, to obtain it, music that is outlandishly provocative, but also strikingly imaginative, innovative, and fun. By 1923 he is the fad of Paris - and then it all starts to go awry. A catastrophic concert given in 1927 at Carnegie Hall, in which a poorly rehearsed and performed "Ballet Mécanique" is received as a Barnum-like piece of gimmickry, seems to be the point of tides turning. His reputation was durably harmed in the US, while he soon fell from favor in France as well. He never recovered from that flop, despite a fugitive revival of interest when Stokowski premiered his 4th symphony in 1944 (Ralph Vaughan Williams: Symphony No.4 in f minor / George Antheil: Symphony No.4) and when he published his famous autobiography "Bad Boy of Music".

Many explanations can be offered, and one is that Antheil's compositional outlook soon evolved, by way of a "French-Stravinskyan" neo-classicism towards a new concern for the big symphonic form. In the process, he himself scornfully rejected his early compositional style - but also lost what made its unique originality. Antheil's later works sound only imitative - without the originality of form. Indeed, imitation was always Antheil's big problem. Later, it was Sibelius, Mahler, Prokofiev, Shostakovich. But already in his early works Antheil could not refrain from paying tribute to his much-worshiped compositional God then, Stravinsky. They are peppered with quotes from Petrushka, Le Sacre, Les Noces, The Soldier's Tale..., to the point of making his music sound derivative, neglecting the fact that his formal processes of construction were much more extreme than Stravinsky's, that his quotation craze can be seen as a forerunner of post-modern Collage, and that his sheer joy at producing a racket went one step beyond Stravinsky (much as Varèse's Amériques compared to "Le Sacre"). The 1st piano concerto is a good case in point. In his autobiography Antheil makes only a cursory reference to it. In the summer of 1922, he inaugurated a concert tour of Germany by going to the first "International Festival of New Music" at Donaueschingen, with the hope of meeting conductors and showing them his symphony "and the new piano concerto". And this is it. Unlike the symphony the concerto wasn't performed. By 1945, Antheil wasn't interested anymore. The manuscript was unearthed in Antheil's papers in 1999. The concerto was given its first performance by this very pianist in March 2001 and the recording made in October. It is a brilliant, brash and colorfully orchestrated work, using the construction processes so typical of Antheil in those years, with the juxtaposition and obsessive repetition of short passages with a strong rhythmic and melodic identity but very little thematic development. It also plunges the listener into a "trivia pursuit" game of trying to recognize the various influences and quotations. Some of Antheil's themes sound like a cliché of "Chinese music" (try 9:45 and 10:40) - a reminiscence of Ornstein's "A la Chinoise", I bet, rather than a pointer to Stravinsky's Rossignol. Petrushka is very present (3:30, again at 14:05 and 16:00, obviously two direct quotations) and so are Scriabin and Debussy in the piano cadenza at 9:40. I also hear Ravel (the arpeggios at 11:00 could be from the two piano version of "Ma Mère L'Oye" or from the Concerto in G), Bloch (the sinuous "Arabian Nights" melody played by the strings at 17:49), Ives (the cacophony at 15:50) and you even get some of Orff's Carmina Burana at 19:21, while the striking final chord reminds me of the same in Schoenberg's "Survivor from Warsaw". But wait! Many of these works were written later than 1922. So, is this a case of Antheil being plundered by the others - not likely, if the concerto lay dormant in his papers. Or was Antheil an unjustly unrecognized precursor, rather than a follower, like this Ernest Fanelli he mentions in his bio, whom supposedly Debussy, Ravel and Satie frequented and borrowed all their compositional techniques from - see my review of Ernest Fanelli: Symphonic Pictures ("The Romance of the Mummy")). Or maybe I am just hearing things that are not in the music. Anyway, the Concerto is brilliant, colorful, inventive and fun. With the other compositions on the disc, it makes for a well-filled (70 minutes), intelligent and coherent, jazz-inspired program (add the companion disc, with more Antheil - his Jazz-Symphony -, Schulhoff and, appropriately, Gershwin: Piano Concertos of the 1920s). Two of the composers (Ravel and Honegger) are French and the two others are American with strong French ties (Copland studied with Nadia Boulanger). The works date from a same time-span, from 1922 (Antheil) to 1930 (Ravel). The Jazz inspiration is more in evidence in Copland (strongly, in the second of the Concerto's two movements) and Ravel (so deftly integrated as to sound Ravelian), Honegger's Concertino, rarely recorded, is a neo-classic piece whose first section could have been written by Stravinsky (another similarity with Antheil ), but whose 2nd and 3rd sections, with their snarling brass, marching rhythm and build-up of tension, sound very typical Honegger. Rische/Sloane's reading of Copland's Concerto will not erase memories of Copland's two recordings - one as conductor with Earl Wild in 1961 (Copland: Piano Concerto And Orchestra/Menotti: Concerto In F For Piano And Orchestra, Copland, Menotti: Piano Concertos), and three years later as the pianist, with Bernstein and New York (The Copland Collection: Early Orchestral Works, 1922-1935). There are spots in the first movement in which they are too solemn and pedestrian, and in the Jazzy second Rische is less muscular than Wild and a bit less idiomatic than Copland. But it is very serviceable nonetheles, and the orchestra has all the rambuctiousness and Jazzy drive required in the second movement. The Ravel gets an excellent performance, very true to the French style established by Marguerite Long and followed by Jean Casadesus, Monique Haas, Nicole Henriot, Jean Doyen and Vlado Perlemuter, in its brilliance, dynamism and light-footedness, but also its relative dryness and refusal to "milk the cow" in the more lyrical and effusive passages. Rische gets truly outstanding support from the Köln Radio Orchestra and Israel Yinon. " |