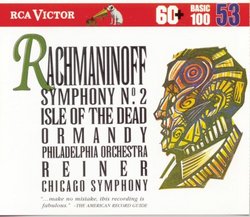

| All Artists: Sergey Rachmaninoff, Eugene Ormandy, Fritz Reiner, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Philadelphia Orchestra Title: Rachmaninoff: Symphony No. 2, Isle Of The Dead (RCA Victor Basic 100, Volume 53) Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: RCA Release Date: 11/8/1994 Genre: Classical Styles: Forms & Genres, Theatrical, Incidental & Program Music, Historical Periods, Modern, 20th, & 21st Century, Symphonies Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 090266802227 |

Search - Sergey Rachmaninoff, Eugene Ormandy, Fritz Reiner :: Rachmaninoff: Symphony No. 2, Isle Of The Dead (RCA Victor Basic 100, Volume 53)

| Sergey Rachmaninoff, Eugene Ormandy, Fritz Reiner Rachmaninoff: Symphony No. 2, Isle Of The Dead (RCA Victor Basic 100, Volume 53) Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsOrmandy and Reiner Show How It's Done Interplanetary Funksmanship | Vanilla Suburbs, USA | 07/07/2002 (5 out of 5 stars) "Sergei Rachmaninoff was tormented by many demons. Following the failure of his First Symphony (1897), he plunged into a harrowing depression, from which he never fully recovered. Its practical manifestation was a ruthless second-guessing of his own abilities as a composer, editing out lengthy and repetitive passages. The two compositions which fell prey most to his red pen were his Second Symphony and Die Toteninsel (Isle of the Dead). Although Eugene Ormandy recorded the Second Symphony three other times - once with the Minneapolis Symphony in 1934 and twice with Philadelphia for Columbia (1951, 1959) - only in 1973 did he return to the work to record the complete score after the huge commercial success of Andre Previn's 1973 recording of the complete version. The 1973 Ormandy version is my favorite, even more than the Previn, which itself is very passionate and energetic. One false charge critics level against Ormandy was that his famed "Philadelphia Sound" was a uniformly applied formula of warm, lush string tonality. This simplistic contention ignores the peerless contributions of the brass, winds and percussion as well as Ormandy's complete and subtle understanding of the music he conducted. Like Arturo Toscanini, Ormandy comprehended the score on an intuitive, emotional, level. What drives this performance are the nuances between and beneath the notes. A cursory listening could lead one to dismiss this performance as "formulaic," especially given the more "animated" performances out there. Given an understanding of Rachmaninoff's music, of his friendship with, and tutelage of, Ormandy -- one realises that the "Philadelphia Sound" was hardly an end in itself. The first movement, Largo; Allegro moderato, opens in a state of dark melancholy. The strings are sumptuous and full-toned. The development of the first theme is gradual; Hints of what is to come are given, but the Philadelphians hold something back. The Rachmaninovian device of building up to the climax is very aptly employed here. One thing I most enjoy about the performance of this movement in particular is that when solo instrumentalists play in the foreground, they do not overshadow the playing of other sections and other soloists, since there's so much going on. Weaving a tapestry of sound, all the threads remain integral, yet brilliantly audible. The introduction to the second theme by the violas is very delicate, punctuated acutely by the lower strings. It is a very solid, yet gentle, rendering, as the winds wander in and out. The bittersweet theme introduced by the solo clarinet leads to the most sensual exposition of this movement I've heard. The movement's end is rousing, jolting the listener with the unexpected: Instead of finishing on a single note played ff on the double-bass, Ormandy substitutes the same note played staccato on the timpani! The second movement, Allegro molto, is the most Russian of all. Like a festive winter's sleigh ride, this panoply of jubilant sound brings to mind Rimsky-Korsakov. There is a concerted buildup of tension to an explosive main theme, which is reintroduced in the symphony's finale. As lighthearted, however, as this movement is, feelings of ecstasy are offset by the ever-present suggestion of mortality. What most impresses me is the sense of contrasts Ormandy and the Philadelphians present: Most striking are the basses' aggressiveness; the false expectation produced by them is spirited away in a deftly-executed and understated ending in mezzo-piano. It is a case of the fall of sledge-hammer as the prelude to the proverbial feather, as in the denouement of the Paganini Rhapsody. The third movement, Adagio, is the most memorable. It begins as a simple liebeslied, through a lucid and evocative solo on clarinet. The emotional theme of the movement is unmistakeable to anyone who has ever loved and lost, a paean to unrequited love. Yet, the movement as communicated by Ormandy and the Philadelphians tells not of morose defeat, but reminiscing of the joy of love, before the loss. With unadorned simplicity, the main theme is imparted by gentle turns of phrasing on a four-note figure for oboe. Strings and brass turn over the theme, seemingly returning the passion to the present time, if only fleetingly. The restatement of the second theme, a six-note figure handed over by the solo French horn in turn to the viola, oboe, flute and clarinet suggest the passage of time since, of seasons changed and events beginning to fade from memory. The adagio ends with the flutes and clarinet. What was once a flame becomes a flicker, slowly dying out. To those who know the movement, this version is the most natural and unforced playing I've ever heard. The finale (Allegro vivace) is an impassioned hymn of deliverance. With brass and percussion in the forefront, much of the opening theme hearkens back to the first two movements. However, those movements' tension and conflict has been resolved. The introduction of the second theme, primarily by strings - and echoed by the flutes and trumpets - gives reassurance that while love may not have triumphed, that life nonetheless does. After a quite dolce interlude - a refrain of the adagio - the triumphal finish kicks in. A celebration affirming life itself, the finale recalls the powerful ending of the Third Concerto. While the 1958 Reiner performance lacks the intensity of Mitropoulos' and the sonority of the Koussevitzky's 1945 recordings, Reiner's still gets under your skin. It flows beautifully, dreamily, other-worldly, impressionistically. This version has the most sonorous brass of any I've heard (which is to be expected, since Reiner was a champion of Wagner and Richard Strauss). The statement of the Dies Irae theme on the horns is the most ominous - I get goose bumps every time! The only disappointment is from the timpanist, who never comes to the forefront, as is required in the penultimate and final climaxes. The ending, on the other hand, shows Reiner's master touch: It is softly and subtly inevitable. Death is triumphant not with a bang, but a whisper." Absolutely superb performances! Interplanetary Funksmanship | 03/23/2001 (5 out of 5 stars) "This CD is an absolute dream: an ideal introduction to Rachmaninov's orchestral work.Eugene Ormandy had recorded the Second Symphony three times before this final 1973 taping. I have heard his 1959 recording on Sony, which is magnificent but heavily cut. Here, Ormandy wisely opens out all the cuts (with the exception of the first-movement repeat) and achieves an interpretation which I believe surpasses his earlier effort. Part of this is because, with the cuts gone, the music makes so much more sense. But I also hear slightly faster tempi and greater flexibility which help to make this vast masterpiece cohere. Sound and playing are both good -- although both were sligtly better on the 1959 Sony account, caught when the Philadelphia Orchestra was truly at the peak of its powers. But there is a new roughness to the sound which I almost prefer, as too much smoothness can, in the wrong hands, turn Rachmaninov's lengthy sequential passages into snoozefests. As always, the Philadelphia Orchestra's strings play Rachmaninov's melodies in a way to make any other orchestra weep with envy.Fritz Reiner's Chicago recording of The Isle of the Dead is similarly superb, and fills out the CD to a generous 76 minutes. Reiner was unsurpassed in this kind of music, and this is my favorite interpretation of Rachmaninov's beautiful tone-poem, along with Svetlanov's more frenetic version, which you will be lucky to be find on Multisonic.There really is nothing wrong with this midpriced CD (well - apart from the packaging and notes which seem to assume that you have the reading age of a 5-year-old). Go ahead and buy it, and enjoy a date with Rachmaninov and his favorite orchestra!" RCA frustrates Interplanetary Funksmanship | 07/17/2000 (3 out of 5 stars) "There really is nothing wrong with Ormandy's reading of this well-known symphony. His experience with it was second only to that of Stokowski in Philadelphia. But the fact remains what's wrong with it is that there's nothing wrong. We have string melismae, lush bowings, a burnishing of brass, all the trademarks of Ormandy's view and school. Which is fine, but...Ormandy himself recorded it better earlier on for Columbia, now CBS Sony. It's even better played, the sound is better, the involvement is strikingly better, so if you like Ormandy performance paradigms, go for that one. The larger issue, though, is other readings out there are far more rewarding. Try Paul Paray on Mercury whose Detroit Symphony gives you spit, shine AND a thrillingly propulsive experience and the sound is wonderful! Willaim Steinberg on Capitol with the Pittsburgh out-Ormandys Ormandy for the flexible, deeply-felt old Romantic School, with beautiful sound. Alfred Wallentein and the LA Philharmonic, also on Capitol, give a joyous and loving reading that stays with you always, a sense of occasion that's hard to capture on a recording. Paray, Steinberg and Wallenstein are just a start. Check out fine contributions by Previn, Slatkin, DeWaart, Kletzki (for a unique orchestral sound) and more. . .The reason to listen to this disk is Reiner's astonishing reading of Isle of the Dead, a performance that has had no peer, before or since. It's a gripping work that leaves you in deep thought, and that's how Reiner impresses it on you, forever. But can I recommend you buy this for one fantastic, shorter work, and a large balance of middle-of-the road? No, you don't have the shelf space. A better alternative is to go to vinyl for the Isle of the Dead in its very good Gold Seal reissue with Reiner's individual La Mer on the other side (hit those old vinyl shops, folks) any of the symphony alternatives above, and pass on this maddening RCA disk...that gets three stars for objective qualities."

|

Track Listings (5) - Disc #1

Track Listings (5) - Disc #1