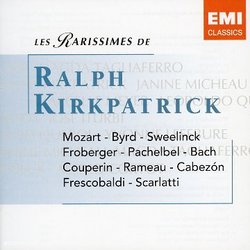

| All Artists: Ralph Kirkpatrick Title: Les Rarissimes : Mozart : Conc. 17, 24 & Recital D Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: EMI Classics France Release Date: 1/13/2008 Album Type: Import Genre: Classical Style: Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 094635183627 |

Search - Ralph Kirkpatrick :: Les Rarissimes : Mozart : Conc. 17, 24 & Recital D

| Ralph Kirkpatrick Les Rarissimes : Mozart : Conc. 17, 24 & Recital D Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsUnmissable Mozart K.491! A. F. K. Monkman | 08/19/2008 (5 out of 5 stars) "As anyone will know who has read either his definitive writings on D. Scarlatti or his monograph on the interpretation of Bach's WTC (a rather broader treatment than the title suggests), Ralph Kirkpatrick was undoubtedly one of the deepest musical thinkers of the 20th century. That his own harpsichord playing was unable fully to keep pace with developments in the realization of the expressive possibilities within early music performance, was entirely due to his having formed a comprehensive piano technique before ever coming to the harpsichord (apparently his hands were so large he could execute trills in octaves with either). But if some expressive possibilities of touch are lacking (and, with the exception of the excellent late recording of Scarlatti for Archiv, an instrument capable of realising them), his expressive abilities in sound-shaping, based on a secure inner ear and the right kind of finger technique needed for convincing articulation in polyphonic textures, have probably never been equalled on the instrument since.

The "Recital" recording (originally ALP 1518) which forms the second CD of this set was one of my first introductions to harpsichord playing, along with the inevitable Landowska, and Rudolph Dolmetsch (whose playing on a few surviving recordings is superb). One thing that made this release so important, is that the material seems to follow a line of 'hidden knowledge' of early keyboard works preserved through the 19th century by composers - Beethoven for one - who cared about the music. Some (the Froberger, Pachelbel and Frescobaldi pieces) had already surfaced in the two Schirmer "Early Keyboard Music" volumes of 1932, which for many people were their introduction to this vast 'other world' of the past. Listening *almost* for the first time since the 1950s (a friend at the BBC made me a cassette tape in the 70s), I find it more a mixed bag in terms of effectiveness than I remembered. The Byrd is faster than ornamentation would suggest (or perhaps even allow judging by the slackening of tempo towards the Gagliarde's end), and there are occasional strange elisions of metre that I've noticed elsewhere in Kirkpatrick's playing (eg. Partita 3, Corrente), but overall, one can only say that despite all (or more accurately, probably just because all else was being sacrificed to this end) the musical sense is imprinted most firmly in the listener's consciousness. I guess this was his thinking, that to convey the musical sense in a literature so unfamiliar and impenetrable (as it must have seemed to most people then) can require the sacrifice of any number of elements deemed authentic in a historical sense, and I for one would second the need (also stressed by RK in the WTC book) for *musical* authenticity, in terms of subjective experience, above all else. For me the main highlights on re-listening turned out to be the Froberger Toccata's opening (if Froberger really didn't know of a 16' string course in the 17th century, he must have wished it), the Pachelbel for its intensity, and the Bach similarly for sheer energy and muscularity (it also gives us a comparison with the Archiv Bach recordings, and for me the sound of the Goble - with some input from Geraint Jones - here wins hands down over the Neupert). That Kirkpatrick stretches a few notational points, in order to highlight musical ones, seems not only forgiveable, but challenging. The French pieces (despite before-the-beat ornamentation) are beautifully characterized: the old and young seigneurs are hilarious, the former doddering - with wonderfully bathetic but somehow moving moments of 'former grandeur remembered' - the latter completely over-the-top and garrulous to boot. Rameau's Les Cyclopes is an unparalleled tour-de-force, one might *almost* believe it possible to 'put giants into a little box'. But, astonishingly - to me at least, remembering the family consensus of my early years that it was a mistake to follow the latter piece with something so much more ancient, and restrained - the Cabezón pieces turn out to be the highlight of the whole disk, the sound being particularly good, and an unimagined intensity building throughout the surprising unpredictability of the harmonic movement arising from the part-writing, from moment to moment. Finally, the Scarlatti pieces are, not surprisingly compelling, despite both a slight tendency for RK's pianistic technique to overpower the music, and a thoroughly 20th century approach to registration changes using the pedals. But the main reason I had to write this review must be the Mozart K491, the C minor piano concerto (which has perhaps only the D minor K466 as companion in creating the kind of musical drama we associate with the Da Ponte operas). The sound and playing from the Geraint Jones Orchestra are inspired and inspiring, and the curiously 'piratical' flavour of the whole not only captured, but expounded - to me at least, who once performed this concerto - as if for the first time. This has to rank as one of the great Mozart performances of the 20th century, and of course Kirkpatrick is in his element here. Cannot be highly-enough recommended!" |

Track Listings (6) - Disc #1

Track Listings (6) - Disc #1