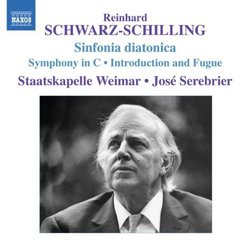

| All Artists: Reinhard Schwarz-Schilling, José Serebrier, Weimar Staatskapelle Title: Reinhard Schwarz-Schilling: Sinfonia diatonica; Symphony in C; Introduction and Fugue Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Naxos Original Release Date: 1/1/2008 Re-Release Date: 8/26/2008 Genre: Classical Styles: Historical Periods, Modern, 20th, & 21st Century, Symphonies Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 747313043576 |

Search - Reinhard Schwarz-Schilling, José Serebrier, Weimar Staatskapelle :: Reinhard Schwarz-Schilling: Sinfonia diatonica; Symphony in C; Introduction and Fugue

| Reinhard Schwarz-Schilling, José Serebrier, Weimar Staatskapelle Reinhard Schwarz-Schilling: Sinfonia diatonica; Symphony in C; Introduction and Fugue Genre: Classical |

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsHighly recommended Schwarz-Schilling's music recording on Na Kuszel Marc | France | 03/01/2009 (5 out of 5 stars) "The outstanding German composer Reinhard Schwarz-Schilling was born in Hanover, Germany on May 9, 1904. He was the son of Carl Schwarz, a chemical manufacturer and Elisabeth Schilling. In 1922, he starded his study of music first in Munich, Germany & Florence, Italy, then in Cologne, Germany: Walter Braunfels and Carl Ehrenberg were his teachers, musical composition for the former & orchestra conducting for the latter. Schwarz-Schilling completed his studies with Heinrich Kaminski in 1927 which was the greatest influence to him: actually Kaminski made his pupil realize the importance of Bach, Beethoven & Bruckner's heritage. In 1929, Schwarz-Schilling married Polish pianist Dusza v.Hakrid and became an organist & choir conductor in Innsbruck, Germany until 1935. A free lance composer from 1935 near Munich, Schwarz-Schilling became a Professor of Composition at the Berlin Musikhochschule. He died on December 9, 1985 and is buried in St.Matthias-Friedhof, the catholic graveyard in Berlin. Forgotten and neglected for a long time, Reinhard Schwarz-Schilling's music is certainly rediscovered nowadays. His musical motto was: "For me, music is the audible product of spiritual energy organized according to unalterable laws" & these laws are the rules of tonal music. As anyone could guess, Schwarz-Schilling's music has nothing to do with Kagel, either Stockhausen or Nono, etc.. It seems that the history of music begins with Buxtehude and is ending with Brahms should anyone feel. Nevertheless, it's not that simple: as one could be able to understand, this music is extremely interesting because of the immediate emotion it brings actually to the listener. Thus, it just doesn't matter if the musical language is tonal or definetely not: Nono would have been extremely unhappy with the only-tonal writing and Schwarz-Schilling with dodecaphonism as well; however this both 20th century composers are exceptional. The works recorded here are significant in many ways of Schwarz-Schilling's music. The "Introduction & Fugue" is taken from the 1932 String Quartet in F minor, movements 1 & 2 and was actually re-written by the composer for string orchestra. Reinhard Schwarz-Schilling did here the very same thing Samuel Barber did with his splendid and well known "Adagio for strings". The "Symphony in C" was written in 1963 when Schwarz-Schilling was aged 59 & this is undisputably an important work. The very same is to be said about the "Sinfonia diatonica" recorded here & written four years before: the slow movement, a "Largo" is really splendid and so is the "Finale". The orchestra of the Staatskapelle Weimar sounds great: the playing of their strings is sensual & Jose Serebrier's conducting is remarkable. Let's hope this is the first but not the last Naxos CD dedicated to Schwarz-Schilling's music & let's thank Naxos for the job they did. A great CD indeed & very cheap as well: the whole thing is highly recommended and truly desserves a 5-Stars rating. " Rather bland music in good performances G.D. | Norway | 12/01/2009 (3 out of 5 stars) "Despite their commitment to interesting and rare repertoire, continental 20th century music is rather thinly featured in the Naxos catalogue, and in that respect this release is very welcome. I am not completely sure Shwarz-Schilling is the most gratifying place to start, however. Reinhard Schwarz-Schilling (1904-1985) was a student of Heinrich Kaminski and as his teacher a staunch and active opposer of the Third Reich (insofar as that is a selling point in itself, why are there no modern recordings of the late-romantic composer Clemens, Freiherr von und zu Franckenstein who would probably sell a couple of discs in virtue of his name alone?). Anyway, Schwarz-Schilling's music is rather conservative in style, with - as the booklet writer makes much of - a strong connection to Bruckner but as reflected through the somewhat austere, grey, somewhat neo-Baroque tradition to which e.g. Kaminski belongs. The main problem is that the music here isn't particularly interesting (apparently I am unable to hear what the other reviewers here do). The Introduction and Fugue for strings from 1948 goes through the moves leaving absolutely no trace in the memory of the listener - it is not bad, but contains nothing interesting either. The Sinfonia diatonica from 10 years later is staunchly conservative, but not much more interesting; mostly bland and unchallenging with few ideas worth savoring, although again I cannot claim that I was really bored while listening to it but the lack of inspiration seems undeniable. The mild-mannered Symphony in C is probably the best work on the disc, and it might be worth hearing once by those who are interested in the music of the period, but if you miss out it will hardly be any major loss (it does, for instance, not hold a candle to the music of near-contemporaries such as Werner Egk, Theodor Berger or Johann Cilensek, to name but three). The performances by the Staatskapelle Weimar under José Serebrier are rather good, with full-bodied strings and a general attention both to detail and overall argument (what there is of it), but to make this music work I think you'd need far more fire and forward momentum than the music receives here. It might be a call for cheating, for I don't think the lack of fire is really due to the performances. Sound quality is fine, I guess. So to sum up, this is undeniably a disc mainly for specialists (although it comes at an attractive price) and maybe you might find something to savor here if you don't expect too much." An important introduction to the music of Germany's 'long-lo David A. Hollingsworth | Washington, DC USA | 12/13/2008 (5 out of 5 stars) "Germany, in 2004, issued a commemorative stamp in the one-hundredth anniversary of the German composer, Reinhard Schwarz-Schilling (1904-1985). And yet his enigma looms and looms large, with barely a mention of his name in music encyclopedias and in other sources that I came across with even recently. Recordings, until now, had very little of his music, with slight exceptions of his songs and organ works that prop up only sporadically. His son, however, is more of a headliner (in Germany and in Europe anyway), Christian Schwarz-Schilling, a German politician.

So, this disc serves as a valuable introduction to his music. Like Carl Orff, Schwarz-Schilling was a pupil of Heinrich Kaminski (1886-1946), a pedagogue and composer who went afoul with the Nazis and became a persona non grata as a result. Schwarz-Schilling likewise resisted the regime and became a freelance composer, performer, and pedagogue (of the Berlin Musikhochschule (Berlin Music College) where he would lead its composition department by 1969). He was also surprisingly prolific, with a whole array of compositions under his belt (and incidentally well revered for his sacred works, songs, and instrumental as well as chamber pieces). The music here shows him as a serious, well-crafted composer in his own right, a keen follower of tradition with a tight, straight and fairly narrow approach to musical creation. He was not an espouser of Germany's expressionist movement or the Avant Garde nor did he embrace sensationalism so common in his day. So anyone who's familiar with Arnold Schoenberg, Benjamin Frankel, or Stravinsky, should expect the opposite here. And if anything else, his music is highly approachable like, for instance, his Introduction and Fugue for Strings (1949) recorded here. Taken from his String Quartet written seventeen years earlier, this is one of the most elegant pieces I've heard (quite as sublime as Heino Eller's Elegia for Harp and Strings (1931) though not quite as modern in sound). Instead, this piece is sort of a homage to the German Classics á la Beethoven and Bach. Neoclassical sort of, but in a different league from, say, Carl Nielsen. His Symphony in C (1963), in a sense Schumannesque, shows the tightness of his argument and thematic development. But it is his Sinfonia diatonica (1957) that I find more interesting. Curiously enough, though perhaps not surprising, the composer lost interest of the work after he performed it in 1958 with Munich Philharmonic and sanctioned the separate performance of the Largo movement (he was particularly not too satisfied with the finale). But here, the ideas have greater spontaneity and freedom than in the Symphony in C and the experience feels less of an exercise. How the first movement begins and ends (with a highly contrasting, dynamic development in between) is especially thought provoking. But the largo second movement, airy in feel, is a work of real ingenuity and sublimity. It reminds me of a slow movement of a Ned Rorem symphony, with that quiet picturesque, almost ethereal quality that grips a listener to one's subconscious. Oh, how regrettable it is, therefore, that like in Rorem's, the movement winds up being too short for its own good. And the finale? I think the type that would do Shostakovich and Antheil proud. José Serebrier's penchant for details pays huge dividends here, and like in Rorem's symphonies (also in Naxos), has such a remarkable sense of structure and verve. I cannot imagine a better molding of the ideas than what we have here and the Staatskapelle Weimar more than meets this great, versatile conductor half way. The booklet essay of Christoph Schlüren (with the composer's assessments of his works recorded here) is excellent as well as scholarly while the recording is first class and ideally detailed and atmospheric. This is one heck of an album to treasure for some time to come. " |