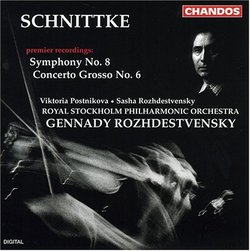

| All Artists: Alfred Schnittke, Gennady Rozhdestvensky, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra, Viktoria Postnikova Title: Schnittke: Symphony No. 8; Concerto grosso No. 6 Members Wishing: 1 Total Copies: 0 Label: Chandos Release Date: 4/18/1995 Genre: Classical Styles: Forms & Genres, Concertos, Historical Periods, Modern, 20th, & 21st Century, Symphonies Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 095115935927 |

Search - Alfred Schnittke, Gennady Rozhdestvensky, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra :: Schnittke: Symphony No. 8; Concerto grosso No. 6

| Alfred Schnittke, Gennady Rozhdestvensky, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra Schnittke: Symphony No. 8; Concerto grosso No. 6 Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD DetailsSimilar CDs

Similarly Requested CDs

|

CD ReviewsSpectral, death-haunted yet affecting C. Symonds | Sydney, NSW Australia | 09/17/2005 (5 out of 5 stars) "The late Alfred Schnittke has, after his death, been accused of writing too much music of variable quality. This debate is still raging although suffice to say that the Eighth Symphony truly is one of his greatest works and indeed, one of the great symphonic works of the latter twentieth century. The charge of oppressive asceticism laid against the Sixth and Seventh symphonies can hardly be held up to this expansive and frankly emotional work. It is as if Schnittke relaxed the skeletal sounds of his previous essays in the genre and, while not quite returning to the dazzling orchestral pyrotechnics of the Fifth Symphony (Concerto Grosso no. 4), creating a work of great sincerity and beauty. The first movement is an obsessive repetition of a wide-ranging (in pitch, not rhythm) melody, seemingly effortlessly varied to touch on all sections of the orchestra. The climax is reached early in the movement and the remainder is a chilling decrescendo, the harmonies becoming more static and dissonant. The second and fourth movements are bitter, angry and Shostakovichian in their use of dissonant intervals to create a long line. They share thematic material, yet shards of the first and third movements invade to further complicate the texture. The eighteen minute third movement is a remarkable achievement. It seems to pick up the wisps of tonality discernable at the end of Mahler's Ninth and convert them into a long elegy for a lost romanticism. The sparsity of texture (often long stretches of monophonic strings) throws the emotive weight totally on the long, twisting and often stunningly beautiful melodies that emerge. The entrance of the low brass towards the end is just one of the profound moments in this stunning meditation on life, and the afterlife. After the rage of the fourth movement, the fifth movement provides a truly wonderful solution to the problems of the previous ones- a slowly ascending c major scale is caught by various instruments, always ppp and the work ends with this visionary cluster. This performance is greatly superior to the one by Polyansky. Polyansky's recordings of the earlier Schnittke symphonies have been wonderful, although I feel that Rozhdestvensky emphasises the deeper emotions in this one, while Polyansky barely scratches the surface. Also, the orchestra's playing is much better. Polyansky's orchestra rushes painfully through the first movement and is not in tune in the last! The Sixth Concerto Grosso is a rather pithy work, containing Bachian string figurations yet its rather limited material does not outstay its welcome in its 15 minute duration. It is however, a better coupling than on Polyansky's- the 'Census List' suite really is second-rate Schnittke. So, all in all, a major release of a major symphony by one of the most intriguing of post-Shostakovich Russian composers." Severe late works which seem to collapse under their own wei Christopher Culver | 07/11/2007 (2 out of 5 stars) "The Russian composer Alfred Schnittke first gained official condemnation in his native Soviet Union and praise abroad for his unique style he called "polystylism", the use of Baroque quotation alongside "dissonant" 20th-century stylizings, and allusions to Mozart alongside snippets of tangos and popular tunes. In 1985, however, he suffered his first stroke, and his music grew more austere and self-contained. Further strokes led to an even greater straitening in his writing. The two pieces here are good examples of how plain and grim his music ultimately became, and though I admire the man for still daring to write under such odds, I find the music itself of much lesser quality than that of his polystylistic heyday.

Schnittke's Symphony No. 8 (1994) begins with a five-note motif passed from one instrumental group to another before growing to a climax. It reminds one somewhat of the repetition of "DSCH" in Shostakovich's Tenth, though sad instead of triumphant, and it seems to be setting the stage for a drama of immense proportions. This sense of approaching action, however, is upset by the second movement, which curiously undoes itself. The third movement, marked Lento, is a slow stringscape. It's ponderous, sentimental in a Messiaen-like fashion...and 17 minutes long, far outstaying its welcome. The fourth and final movement, instead of offering suitable closer, ends after a mere two minutes. The third movement of the symphony exhibits a fatal flaw of much of Schnittke's late work: things tend to drag on too long. There are other examples, but besides this I think the watching-paint-dry opening of the Symphony No. 6 is the most notorious. But beyond that, I have a hard time appreciating the bulk of Schnittke's symphonies simply for their lack of anything new. Schnittke was retreading ground already discovered by Mahler and unnecessarily repeated by Shostakovich. Having been dazzled by the six (soon seven) symphonies of Per Norgard and the single but brilliant symphony of Sofia Gubaidulina, I appreciate the symphonic genre as a chance to showcase never before heard concepts in massive proportions. As much as many of Schnittke's symphonies offer some repertoire that's new but which won't upset the conservatives too much, they fail to teach the fan of contemporary music anything that he didn't know before. The Concerto Grosso No. 6 (1993) doesn't drag as much as the symphony. Indeed, it's Schnittke's shortest effort in the genre at 14 minutes long. And not only is it unusually short, but it leaves behind the ties to Bach that are the hallmark of his earlier concerti grossi. Unfortunately, here too Schnittke falters, for the dramatic potential that seems in store among violin and piano soloists and orchestra is never fully realized, and the piece comes to an end at a seemingly random moment. The performance here is also flawed, for while the Concerto Grosso No. 6 was actually written for the Rozhdestvensky family, I find their take on it less confident than that on BIS, where Ralf Gothoni conducts the Tapiola Sinfonietta. Those new to Schnittke's music would do better, I think, to start with two Moscow Studio Archives discs. The first contains the Concerto Grosso No. 1 and the Cello Concerto No. 1, while the second contains the Concerto Grosso No. 2 and the Viola Concerto. And while fans of Schnittke's late period may take offense at my low rating, I can only call it as I see it, and I invite those fans to explain what fascinates them in the late works in the comments here or a separate review." |

Track Listings (8) - Disc #1

Track Listings (8) - Disc #1