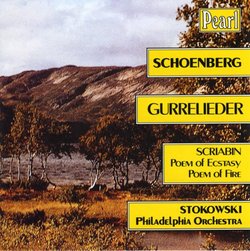

| All Artists: Arnold Schoenberg, Alexander Scriabin, Leopold Stokowski, Fortnightly Club, Mendelssohn Club of Philadelphia, Philadelphia Orchestra, Artur Rodzinski, Abrasha Robofsky, Benjamin de Loache, Jeanette Vreeland, Paul Althouse, Robert Betts, Rose Bampton Title: Schoenberg: Gurrelieder; Scriabin: Poem of Ecstasy; Poem of Fire Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Pearl Release Date: 2/3/1995 Genres: Special Interest, Classical Styles: Opera & Classical Vocal, Forms & Genres, Sonatas, Historical Periods, Modern, 20th, & 21st Century, Symphonies Number of Discs: 2 SwapaCD Credits: 2 UPC: 727031906629 |

Search - Arnold Schoenberg, Alexander Scriabin, Leopold Stokowski :: Schoenberg: Gurrelieder; Scriabin: Poem of Ecstasy; Poem of Fire

| Arnold Schoenberg, Alexander Scriabin, Leopold Stokowski Schoenberg: Gurrelieder; Scriabin: Poem of Ecstasy; Poem of Fire Genres: Special Interest, Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsSchoenberg-Stokoswki: A Vast Architecture in Sound Thomas F. Bertonneau | Oswego, NY United States | 10/13/2000 (5 out of 5 stars) "I crusade - inveterately, it seems, and probably vainly, too - on behalf of what the review magazines usually call "archival" or "historical" documents: They mean recordings from prior to 1950 or so made in the era either of electrical registration of the master-copy on acetate or metal discs or of early magnetic-tape preservation of the broadcast or studio performance. (The two eras overlap.) I thus constantly confront the audiophile mentality: "Why would I want to hear those pops and ticks from the lacquer platters, or the static-hiss and low fidelity from antiquated magnetic tapes?" My answer has become resolute and invariable: "The sound captured by engineers with that pre-stereo, pre-solid-state, pre-digital equipment is certainly different from what modern ears expect, but it is not inferior." In some cases, indeed, the old recordings, especially the early magnetic tapes from Germany and Holland, yield a sense of natural orchestral sound that no stereo or digital item has ever captured. It's true that stereo, in particular, can enhance a listener's appreciation of certain kinds of music, especially of highly contrapuntal music or, say, of chamber ensemble music. Between Bernstein's Tchaikovsky, however, from the 1960s and Mengelberg's from the 1930s, I'd say it's a toss-up: What will decide a fellow is his judgment of the performance, not of the technical perfection of the registration. All of which brings me to one of the most audacious and successful choral-orchestral recordings ever made: Leopold Stokowski's 1932 (that's right - 1932!) playback version of Arnold Schoenberg's gargantuan, Tristanesque cantata, "Gurrelieder," based on texts by the Danish poet Jens-Peter Jacobson. The reissuing house is Pearl, which specializes in this sort of thing. By Zeus, but this is sprawling, indulgent, harmonically overripe music for soli, chorus and (huge) orchestra! Schoenberg distills everything he had learned from Wagner and Mahler into his great tapestry, which he began around 1900, set aside, and did not complete until 1912. Stokowski, in spoken remarks, calls "Gurrelieder" a specimen of vast "architecture in sound." Now it is Pearl's policy, in distinction to that, say, of Dutton Laboratories, not to fiddle with the sound on the master-documents, except to filter slightly some of the noise from worn platters. Even so, the achievement of the RCA engineers in 1932 will astonish: The orchestral groups are clearly differentiated, the vocal soli sound clearly and the words are audible; the choruses (the real challenge) come through with immediacy and a minimum of distortion. What also manifests itself undeniably is Stokowski's vital commitment to this music. It was Stokowski who gave the North American premiere of Mahler's Eighth Symphony, in Philadelphia, in 1916. We hear the Philadelphians in Schoenberg, too, their velvety strings and their crisp, singing woodwinds. The brass snarl effectively when the score requires it. The tutti passages defy any expectation of what "old" recordings should sound like. Stokowski liked these towering late-Romantic edifices and it tells. Pearl fills out the second disc with two Scriabin items, "The Poem of Ecstasy" and "Prometheus," recorded in the midst of the depression with reduced forces but worth getting to know nonetheless. The real prize is Schoenberg."

|

Track Listings (16) - Disc #1

Track Listings (16) - Disc #1