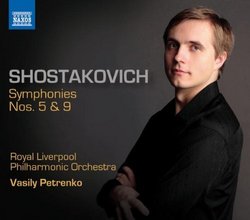

| All Artists: Dmitry Shostakovich, Vasily Petrenko, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra Title: Shostakovich: Symphonies Nos. 5 and 9 Members Wishing: 1 Total Copies: 0 Label: Naxos Original Release Date: 1/1/2009 Re-Release Date: 10/27/2009 Genre: Classical Style: Symphonies Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPCs: 747313216772, 747313216772 |

Search - Dmitry Shostakovich, Vasily Petrenko, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra :: Shostakovich: Symphonies Nos. 5 and 9

| Dmitry Shostakovich, Vasily Petrenko, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra Shostakovich: Symphonies Nos. 5 and 9 Genre: Classical |

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsClose to the top of a very long list Steen Mencke | Denmark | 02/21/2010 (5 out of 5 stars) "At present I have nineteen different versions of the Shostakovich fifth in my classical collection, ranging from vintage versions by Mravinsky, Kondrashin and Ancerl to more modern ones by conductors like Gergiev, Ashkenazy and Temirkanov. Still I consider Petrenko's recording to be among the very finest beasts in my herd due to a well-thought-through aproach and a very consistent and in every detail finely crafted reading. Many years ago I had the good fortune to be present at an unforgetable rehersal of the symphony our National Radio Orchestra had with the no longer active (but still with us at the tender age of 97!) German conductor Kurt Sanderling, who was in the audience at its first performance back in 1937, and who knew the conditions of Stalin's Russia first hand having fled there from Nazi Germany the year before. His many instructions to the orchestra regarding the numerous instances of the music tapping directly into the oppressive every-day life during the purges of the mid-thirties was a wonderful insight into this awsome piece of music, and with so many of those hints present in Petrenko's version, I all but feel that he must have been there on that occasion as well. Especially the many life-like details in the Party day persiflage of the second movement are done to perfection, and the stumbling, pleading notes of the little violin solo - according to Sanderling the musical likeness of a little girl attempting to recite a short thank-you speech to Stalin while handing over a bouquet of flowers - is moving in the extreme. The Largo movement is rather slow (too slow, I'm sure many would say - but then again the tempo is Largo, so how could it be?!), but unlike the equally slow ditto of Bernstein's 1979 recording it never turns stale, and it very effectively conveys the desolation and sense of insecurity Shostakovich no doubt felt at the time of its composition. Like Masur in his recent recording (live with the LPO, 2004) Petrenko drops the speed strangely early in the finale (at the start of the kettledrum motive), which must be a new way of reading the score that I never encountered before Masur, and which isn't particularly to my taste. It makes the whole finish, and the repeated A-notes in particular, drag almost unbearably, but maybe that is how Shostakovich would have wanted it, given that the Cyrillic letter "a" means "I" in Russian. As he put it to Sanderling regarding the victorious conclusion to the symphony: "It is about me, me, me - not them", them being the communist elite. The ninth symphony is a very different animal to parade compared to the two-faced and sarcastic fifth. Its spirit of playful lightness contrasted with slow, contemplative passages came as a great surprise to the audience at its first performance, and it landed Shostakovich in hot water with the authorities yet again, this time to such a degree that he didn't compose a symphony again till after Stalin's death eight years later. Petrenko makes the best of light and darkness both, and though I doubt the symphony can be said to carry any deep philosophical message, it is given a very thorough and sympathetic reading. The recording is very clear and spacious with fine technical playing by the RLPO. Only in the most voluminous tuttis the sound turns a bit distant and confined, whether due to limiting conditions at the recording location or to spare the equipment, I don't know. All in all a most commendable disc available at an almost rediculous price. " Vasily Petrenko, RLPO: Shostakovich Syms 5 & 9: Second volum Dan Fee | Berkeley, CA USA | 11/05/2009 (5 out of 5 stars) "The first volume in this ongoing series from Naxos was a quality reading of the eleventh symphony from these same forces. New conductor Vassily Petrenko has to publish in the long shadows cast by Naxos' former distinguished Shostakovich conductor, Ladislav Slovak. The Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra (RLPO) has an easier comparison task, because the earlier Naxos series used the Slovak Radio band. RLPO is a step up, though the Slovak RSO did play towards the angels of their better musical natures in the old Shostakovich cycle. As it happens, I received this second volume right after watching Michael Tilson Thomas and San Francisco do the Shostakovich fifth in their new video-music series, Keeping Score. That media piece lays out a compelling vision of what the music captures, with lots of intermittent flash back contextualizing from Soviet history in general, and from the composer's life and work in particular. The MTT keys to this symphony are demonstrated to be quite apt. With that juxtaposition, it was a bit of shift to next spin the new Petrenko reading of the famous fifth symphony. MTT makes much of the ta-da figure that many different composers have used to announce heroic motifs and attitudes in their music across different music history periods. Many readings open with the instant recognition of a forceful interval and oscillation in this famous string flourish. Petrenko? Well, he down plays the flourish, alternatively, in favor of clear line, and perhaps already suggesting that - as we all know from the composer's life and the Stalinist era - not all is well. Given such touches of clarity and simultaneous unease, this opening call or gesture is less heroic and more palpably questioning? An association perhaps would be the "Muss es sein" motif. Think the Beethoven quartet; think Franz Liszt in his tone poem; think Cesar Franck opening his unique French symphony. So as the first movement music quickly delves down into the dark depths - Petrenko is less setting up stark contrasts and implied subtexts of unease, than he is reaching for a deep sense of a surprisingly sophisticated common humanist core, nevertheless wracked by injustice, oppression, suffering, and melancholy isolation of each from each under Stalin. When the fugal march kicks in, we know the Secret Police are in the neighborhood in the wee morning hours, knocking down doors. This scene painting is just barely scary enough; but at the same time, ironic in its cinematic deftness, seemingly touched by the lightest of Keystone Cops movie pianist associations. As the march gathers momentum, the unison octaves break forth - fired with both protest and threat and stubborn loss. High woodwinds and brass inflect folk song lift; not even midnight visits from the Secret Police can completely dehumanize us. We can remember morning light, we can still dream of some past warm sunshine. All this is played in Petrenko-Liverpool's first movement; but he and the players are never exactly hammering away at the music with fists full of faux-heroic blunt phrasing. It is the slim weight of a knowing glance in silence, a deep core sense of oppressed uneasiness that brings us all together in this first movement. Before we have had a chance to time it on the clock, the celeste is chiming us all away into the hidden thin air of oppressed human brotherhood-sisterhood. The officious musical business of the scherzo-like second movement brings us outside, into the day's normal business, complete with dutiful allusions to the Official Party Line of the moment, as well as the flirtatious exchanging of further glances with our willy-nilly Circus of denials that somehow still remind us how possible our human freedoms really still are. This sounds out typical Shostakovich public square music, just as Stravinsky makes the Shrove-Tide Fair into all teeming humanity in his Petrushka ballet. Thus, subtly, the Officious Party Line March rhythms teeter on moments of freer dance. Petrenko's third movement in this fifth symphony plunges us right back into profound isolation, unease, and the private human workings of suffering, longing, and remembrance, all forbidden to be openly spoken in Party Electric Bulb Daylight. Friends have been taken away in the brutal dark of the night. Family have been taken away. Growling up from the low strings, welling up in frank yet restrained dignity of human feeling, we can mourn their loss as our loss. We can feel to explore what surviving signifies, what remaining alive, behind, signifies. Mourning stretches towards grief-stricken song, lament, sobs of melody piecemeal. Full, long melodies surging through the stringed instruments seem to sing of resolve: Never Forget. Low string gestures wind us down the scale again, just as they wind us up the scale in preparation for the great bass solo voice recitative that opens Beethoven's Ninth. Chime evocations let us out the back doors again, offering a safe exit unseen. Petrenko and Liverpool announce the final movement opening march with gusto; but sophisticated touches of cinema accompaniment still remain. Perhaps the show of raw state force unopposed is not as total as it claims to be? Outright Keystone Cops cinema harmonies burlesque raw force. Everybody is watching everybody, busy and running around just as ordered. The train wreck that is the state seems clear in a subtle, sub-textual way; so, too, does the antic futility of power, control, and group-think social or political or cultural conformity. The music winds down into free spaces again, tinged with isolation, melancholy, lighted up with wordless musical truth telling. The march theme starts again, low reaching high, phrasing a newish questioning lyrical shape. Counterpoint explores the supporting space for the melody that can sing like folk. A more expansive version of the march reveals a vexed historical version of the people, stretching in a larger vista of victims and survivors, reaching across all the cruel iterations of the old monarchy and new secular state. Unison octaves stand tall in the close: We are still here, hurting. The reading of the composer's ninth symphony is all frisk, wit, frolic, and Till Eulenspiegel pranks. Petrenko and Liverpool freely bring out the play of circus fair touches. Braying trombone flourish, woodwind and string acrobatics in reply. The repeated flourish with its wisp of clown in makeup melody in reply are developed freely, irrepressible. The Moderato slow second movement is one of those typical Shostakovich evocations of wordless personal-private musings, isolated, permeated with sadness and regrets as nearly objective, stolid facts of life which cannot be wished away or dissolved in any hard, open work of mourning. In passing moments of nearly consonant harmonization, the winding, aching melodies almost beckon to arrive in those familiar Mahler-esque neighborhoods we know as all of those Mahler 'flower music' movements. But no, this will not actually happen; no flowers in the Shostakovich meadow will bloom. Suddenly the Presto third movement whisks us away, catching us up in just how getting busy with everyday, mundane life business will take us away from isolation and melancholy musings while also perhaps distracting the ever-present police state scrutiny from us as targets of hot suspicion. Then suddenly the Largo fourth movement is all serious business. Are we suddenly just now hearing that yet another fond friend has disappeared in the middle of the night? Which leads right into the closing faster music, wrapping up with cinema, circus acrobatics, and theatrical alarms which stand in for real alarm. Five Stars. Petrenko is not sheepishly imitating others in his Shostakovich; not even the great Mravinsky. Liverpool is playing with notable precision, involved, matched to Petrenko's vision." Limp and Unconvincing 5th--Deft and Mercurial 9th. David N. Loesch | Seattle, WA | 07/13/2010 (2 out of 5 stars) "I recently purchased, at an absurdly low price, Vasily Petrenko's searing reading of the Shostakovich Eighth on Naxos. The interpretation is gripping, the orchestral playing superlative and the recorded sound exemplary. It goes right to the top of my recordings of that work. Consequently, I couldn't wait to hear Petrenko's take on the Fifth in the same series.

I was in for a major disappointment. Virtually everything that was so right about the Eighth is wrong with the Fifth. To say that the tempo choices are eccentric would be an understatement. I am not going to join the great debate among musicologists and conductors about the proper tempi in the fourth movement other than to say that Petrenko slows the tempo to a crawl much earlier than in any other performance I have heard, and the effect is disconcerting. Where the choice of abnormally slow tempi is most annoying is in the first movement. It is so slow at one point early on that a beautiful long melodic line completely loses its definition. The opening motif in the strings is curiously devoid of drama, nor does any dramatic tension develop as the movement progresses. In this first movement, Shostakovich masterfully manipulates the simplest thematic material into a tight, complex and convincing structure filled with tension, contrast and surprises. Petrenko renders the whole thing limp and shapeless. An unusually wide dynamic range doesn't help. This first movement is practically fool proof in its ability to engage the listener from beginning to end, but somehow Petrenko manages to make it boring. It doesn't get much better. The scherzo lacks bite, and the largo is devoid of all pathos or passion. If nothing else, the finale is "interesting"--judge it for yourself. On a happier note, the Ninth is a delight. Petrenko's light touch, transparent textures and quick tempi bring out all the tongue-in-cheek humor of this "Anti-Ninth Symphony." Expected to produce a properly ponderous ninth (possibly dedicated to Stalin himself,) Shostakovich effectively thumbed his nose at the establishment with a disarmingly clever bit of satire. It is filled with musical jokes, parodies of Hayden and Beethoven, ridiculous juxtapositions and structural absurdities. Petrenko has exactly the right take on this marvelous piece of fun, from the opening measures to the free-for-all at the end. Do yourself a favor and buy Petrenko's Eight. This disc is worth it for the Ninth only, but it is cheap enough. " |