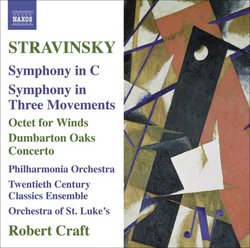

| All Artists: Stravinsky, Craft, Orchestra of St. Luke's, Philharmonia Orchestra, Twentieth Century Classics Ensemble Title: Stravinsky: Symphony in C; Symphony In Three Movements Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Naxos Original Release Date: 1/1/2008 Re-Release Date: 1/27/2009 Genre: Classical Styles: Chamber Music, Forms & Genres, Concertos, Historical Periods, Modern, 20th, & 21st Century, Symphonies Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 747313250721 |

Search - Stravinsky, Craft, Orchestra of St. Luke's :: Stravinsky: Symphony in C; Symphony In Three Movements

| Stravinsky, Craft, Orchestra of St. Luke's Stravinsky: Symphony in C; Symphony In Three Movements Genre: Classical |

Larger Image |

CD DetailsSimilar CDs |

CD ReviewsNeoclassic Stravinsky in Terrific Performances J Scott Morrison | Middlebury VT, USA | 02/07/2009 (5 out of 5 stars) "Naxos has done us a mitzvah by reissuing a series -- this is the tenth CD -- of recordings made by Robert Craft in the 1990s on first the Music Masters and later the Koch International labels. They have recombined them on their own CDs, and indeed this disc has six tracks from Music Masters (1-6) and seven from Koch (7-13). The disc includes two of Stravinsky's symphonies -- Symphony in C, and Symphony in Three Movements -- combined with two of his delicious chamber works, the Octet for Winds, and the Dumbarton Oaks Concerto.

The Octet for Winds, played here by members of the Orchestra of St. Luke's, is a sassy, light-hearted piece for eight winds. Premiered in 1923, it was dedicated to Stravinsky's mistress, later wife, Vera de Bosset. It is in three movements: a kind of overture, a theme and variations, and a jazzy finale. It is probably Stravinsky's first completely neo-classic piece and it has remained a great favorite of instrumentalists and audiences alike. The virtuosos of the St Luke's play it in great style. The Dumbarton Oaks Concerto (1938) is named for the Washington DC estate of Robert and Mildred Bliss, great friends of Stravinsky, and it was premiered there with Nadia Boulanger conducting. Written for ten strings and five winds, it too is in three movements (delightfully choreographed years later by Jerome Robbins) with the typical concerto grosso fast-slow-fast form. In my mind it will always be inextricably connected with the equally ever-fresh Jeu de Cartes ballet because the two were on my very first Stravinsky recording back in the mid-1950s. But it makes a perfect partner for the Octet as well, sharing as it does Stravinsky's nose-thumbing wit. And this is a lovely, spot-on performance, no surprise with an old Stravinsky hand like Craft on the podium. We switch performers for the two symphonies, with Craft conducting London's Philharmonia Orchestra. The Symphony in C (1940) begins with an allegro that, although it is Stravinsky's longest single-meter work since the early 1900s, constantly surprises and delights with its off-kilter accents and unexpectedly long rests. In between writing the first and second movements Stravinsky contracted tuberculosis and had to move to the same sanitarium where his wife and daughter had only recently died of the disease. The second movement, perhaps not surprisingly, is a sad larghetto. The last two movements were written a few months later in the United States, the third in Cambridge, the fourth in Hollywood. A peripatetic work! The scherzo, marked allegretto, is the only one of the four movements that has the dizzidly ever-changing meters so typical of Stravinsky. It is built on manipulations of the interval of a fourth and has a passepied as its trio. The finale begins with a largo section with solo bassoon intoning against muted brass playing diminished chords; it resolves to a vigorous C major sunburst at the beginning of the main section, Tempo giusto, which after a development section quietens and ends on a serene final chord that combines C major and G major. The Symphony in Three Movements (1942-45), while neoclassical, is a more emotionally expressive work than the other works here. Written during the height of World War II, it understandably reflects that. The opening measures grab you by the lapels and propel you into a maelstrom of conflict. The movement was inspired by a war film that depicted the use of scorched earth tactics in China by Japanese troops. The middle movement, written separately and actually originally intended for a movie made from Franz Werfel's 'The Song of Bernadette', is a dreamlike and lyrical piece that features obbligato harp. For the finale, while actually completed during the time of the Japanese surrender, Stravinsky indicated its marchlike tempo was dictated by images of German soldiers goose-stepping across Europe. But the march grinds to a halt and the movement ends with a fugue initiated by piano and harp and connoting the rise of the Allies. It ends on, to quote Stravinsky, 'a probably too commercial D flat sixth chord that . . . tokens my exuberance in the Allied triumph.' As always, Craft is the Stravinsky conductor nonpareil. These performances were treasured when they first came out in the 90s and they are just as wonderful now in this newly remastered release. Scott Morrison" |