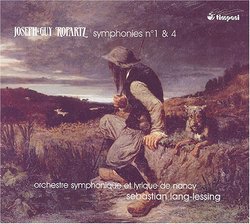

| All Artists: Ropartz, Lyrique De Nancy Orch, Lang-Lessing Title: Symphonies 1 Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Timpani Original Release Date: 1/1/2006 Re-Release Date: 1/24/2006 Album Type: Import Genre: Classical Style: Symphonies Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPCs: 675754871727, 3377891310936 |

Search - Ropartz, Lyrique De Nancy Orch, Lang-Lessing :: Symphonies 1

| Ropartz, Lyrique De Nancy Orch, Lang-Lessing Symphonies 1 Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsA Breton Symphonist Thomas F. Bertonneau | Oswego, NY United States | 11/24/2006 (5 out of 5 stars) "The symphony, an Austro-German invention, soon found adherents among composers in the other European countries. With the exception of Hector Berlioz's "Symphonie fantastique" (1830) and "Harold en Italie" (1834), however, no significant French examples of the symphony register in the musicological chronology until after the middle of the Nineteenth Century, when the stimulus for them came not from Beethoven, as it did for the generation of Mendelssohn and Schumann in Germany, but rather from Franz Liszt and Richard Wagner. The beginnings of the great tradition of the French Symphony belong to César Franck (a Belgian by birth) and Camille Saint-Saens in the 1880s. Franck contributed only one item to the genre, his Symphony in D-Minor (1888); Saint-Saens contributed several, but found an audience with only one, his Symphony in C-Minor (1886) known as the "Organ Symphony." These two works set the pattern for what followed. Franck and Saint-Saens borrowed from Liszt's symphonic poems the "cyclic principle" by which the thematic material for all the movements of a work derives from basic "cells" or motivic patterns exposed in the opening bars of the first movement. They borrowed from Liszt's "Faust Symphony" the spiritual ground plan of an emotional journey from minor-key darkness into major-key light. In both the D-Minor and the C-Minor Symphonies, spiritual struggle yields at last to redemptive triumph in an extended chorale. The emergence of the French Symphony also represents the esthetic sublimation of Catholicism at the moment when the influence of actual Catholic doctrine on the French nation began to decline. Now Franck had many students and admirers who imitated his compositional gestures. Thus the symphonies of Vincent D'Indy, especially the Second in B-Major (1904), resemble those of the "Pater Angelicus," as Franck's beneficiaries called him. D'Indy in turn had many students and admirers, so that the Franck-pattern for a French symphony became a kind of artistic orthodoxy. Individual composers often adhered to the orthodoxy while also struggling to express within its limitations their own esthetic vision. This battle is evident in such works as the Symphony in B-Flat (1889) by Ernest Chausson, the four symphonies by Albéric Magnard, and in the symphonies of Charles-Marie Widor and Louis Vierne.

Two Breton composers became late adherents of the "Schola Cantorum" tradition inaugurated by Franck and D'Indy: Charles Tournemire (1870 - 1939) and Guy Ropartz (1864 - 1955). Like Franck himself and like Widor and Vierne, Tournemire and Ropartz trained as organists and as musician-participants in the Catholic liturgy; both appear to have been genuinely religious and devoted. Ropartz became rector of the Conservatory of Nancy in 1919, however, withdrew from concretizing and modestly made only token efforts in advancing his own music. The compact disc era has now revealed Ropartz as an exceptionally accomplished symphonist who conformed to the broad outlines of the Franck type of symphony but at the same time infused the pattern of it with individual gestures and original melodic and harmonic content. Ropartz famously wrote that, "La tradition n'est pas académisme," or "tradition is not academicism," a view that he never ceased to observe in his own compositional activity, as his symphonies attest. Volume I of the new series of compact discs from Timpani pairs Symphony No. 1 (1895) with Symphony No. 4 (1910 / 11). Sebastian Lang-Lessing leads the Orchestre Symphonique et Lyrique de Nancy. Ropartz described his Symphony No. 1 as "On a Breton Chorale," rather as D'Indy described his Symphony Concertante (1886) as "On a French Mountain Air." Ropartz's title reflects his determination to highlight the folkloric and liturgical traditions peculiar to the region of Brittany, a department of the French Republic that has clung tenaciously to its old language and its regional dialect and to the legends of its medieval independence from metropolitan France. Brittany is Catholic, but there is something Pelagian or Protestant - or maybe Nordic - about Breton Catholicism. Symphony No. 1 observes the Franck-derived plan for a three-movement work, but it also conforms to the model of a through-composed set of chorale-variations in the manner of the greatest of all Protestant composers, J. S. Bach. In the First Movement Ropartz introduces the chorale over wave-like drum-rolls before launching into the main Allegro; he develops his material continuously, after the manner of Bach or Franck. Ropartz derives from the chorale contrasting "light" and "dark" themes, whose conflict pays homage to sonata form, just as it also obeys the technique of the "Schola." In the Second Movement Ropartz transforms the chorale into a rustic lament, first heard on the English horn and passed from one instrument to the next. Scherzo-like elements relieve the general somberness; the lament returns. In the Finale, Ropartz trades cloudy skies for sunny ones, with backward glances at the two foregoing movements until the chorale returns in augmentation for the apotheotic triumph of light over darkness in the true Franck style. Symphony No. 4 shows Ropartz distancing himself somewhat from the "Schola" pattern: the textures are less saturated, the harmonies less chromatic than before; a new simplicity is apparent. Again there are three movements in a Fast-Slow-Fast sequence, played nearly without pause; again the material for all three movements first appears in the opening bars of the First Movement. In Symphony No. 1, Ropartz puts the weight on the First Movement, whereas in Symphony No. 2 he puts it on the Second Movement, which has the character of an extended nocturne, interrupted by rustic dances that fulfill a scherzo function. The Finale is an engaging blaze, subtler than in Symphony No. 1 but by no means disappointing. Lang-Lessing has a clear idea of these scores and directs them with conviction. The Nancy orchestra plays beautifully - I call attention to the many gorgeous wind-solos in the two slow movements. Timpani's recorded sound fits the music perfectly." |

Track Listings (6) - Disc #1

Track Listings (6) - Disc #1