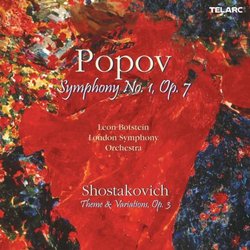

| All Artists: Gavriil Nikolayevich Popov, Dmitry Shostakovich, Leon Botstein, London Symphony Orchestra Title: Symphony 1 / Theme & Variations Op 7 Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Telarc Release Date: 11/23/2004 Genre: Classical Styles: Historical Periods, Modern, 20th, & 21st Century, Symphonies Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 089408064227 |

Search - Gavriil Nikolayevich Popov, Dmitry Shostakovich, Leon Botstein :: Symphony 1 / Theme & Variations Op 7

| Gavriil Nikolayevich Popov, Dmitry Shostakovich, Leon Botstein Symphony 1 / Theme & Variations Op 7 Genre: Classical

A near contemporary of Shostakovitch, Gavril Popov found his 1934 Symphony banned by the Soviets for reflecting "the ideology of classes hostile to us." Popov escaped worse by toeing the line in his future compositions, bu... more » |

Larger Image |

CD DetailsSynopsis

Amazon.com A near contemporary of Shostakovitch, Gavril Popov found his 1934 Symphony banned by the Soviets for reflecting "the ideology of classes hostile to us." Popov escaped worse by toeing the line in his future compositions, but this exuberant work well deserves revival. It's long, somewhat disorganized and sprawling, but chock-full of brilliant orchestral effects and rhythmic power. The opening is reminiscent of Prokofiev's Lt. Kije, with a massive orchestral "sneeze" followed by a snappy section that gives the band a nice workout. The long first movement has an appealing manic drive shared by the third and final movement, which has a raising-the-roof ending. In between comes a long, lyrical slow movement teeming with ideas. Popov's work is aptly coupled with the teen-age Shostakovitch's Theme and Variations from 1922, a superior student work that sheds new light on the composer's development. Botstein and the LSO are persuasive advocates and demonstration quality sound adds to the disc?s appeal. --Dan Davis Similarly Requested CDs

|

CD ReviewsThe Essences of Popov & Shostakovich in the Era of Discovery David A. Hollingsworth | Washington, DC USA | 11/29/2004 (5 out of 5 stars) "The beauty behind repeated listening is the opportunity to redefine one's reactions after the first encounter. And when a subsequent recording of the piece is involved, then the redefinition can become, quite frankly, even more awesome of the experience. That is the case here; the encountering that is more rewarding and gripping than I could've possibly anticipate and Botstein with the London Symphony Orchestra under the excellently engineered Telarc recording made that possible. This album will be a revelation for quite some time to come. The first recording of Popov's First Symphony that grew on me since 1996 is the Olympia's re-issued 1989 recording featuring Gennady Provatorov and the Moscow State Symphony Orchestra (no, not the same orchestra that's on Naxos). What I like about Provatorov's take is his overall emotional punch, the impact that grips the listener to one's core. The piercing, schizophrenic opening is a great example of this; the opening that is as frightening and powerful as ever under his hands. But the ensuing development has that sense of paranoiac anxiety that even Myaskovsky can relate to in his Sixth. Provatorov, quite a master of shaping and tone painting brings out the solemn quality of the slow section to full effects. But listen to how explosive that section becomes at 5'13" as the schizophrenia becomes even more pronounced and fateful. The climax at 14'58" is exemplary under his hands, effectively poignant and anguished, but also defiant. This is, like Myaskovsky's Thirteenth (1932), the despondency at its most compellingness. Botstein, however, very much like his April 11th, 2003 performance with the American Symphony Orchestra in New York (which happened to be the US premiere of the work), goes much deeper. His tempi is more grander and majestic, but hardly with less than emotionally penetrating. Take the development after the initial outburst, the way he becomes more analytical in the psychology behind the music and the man. And the tone painting especially by the London Symphony (brass and percussion sections in particular) is more successful in bringing out the fear yet the uncertainty behind the work (listen how the brass and bass drum portray of primitiveness of fear at 2'18"). Botstein's treatment of the slow section is even more mystifying and elusive than Provatorov's, yet hardly with less impact particularly when the section heats up. But Botstein's take on the elaborate central development is likewise deeply analytical and emotional as well, especially when during the climax at 15'36", the sense of defiance gives way to feelings of pure anguish & Dies irae in majestic proportions. Remarkable stuff here as in the lyrical Largo movement, where, again Botstein is more emotionally penetrating than Provatorov. The movement is lyrical, but not so as clear-cutting as one might expect. With Botstein, the sense of inner loss and contemplation are even more conspicuous, and when the music becomes more emotionally charged, the agitation and poignancy of anguish remain. But the movement retains its humaneness and humility, whereas the finale affirms hope for mankind. Jovial and hopeful the finale is in Provatorov's rendition, the sense of victory and hope is more harder earned under Botstein (and again the brass and percussion bring forth more of the schizophrenic nature of the first movement, a reminder that the reality of Stalinism remained though the will to live remained also). With that all said and done, Provatorov defines standards and expectations of the piece. Botstein re-defines them. Some annotations must be made on the man and the music. Gavriil Nikolayevich Popov (1904-1972) was in essence "Shostakovich's Long-Lost Brother" (in using Laurel Fay's description of him in his April 6th, 2003 New York Times article). Emerging during the avant-garde movement of the 1920s, he achieved fame and notoriety with his Septet of 1926, the piece that represented the best of the avant-garde tradition in Russia and abroad. As with Shostakovich, Popov's creative instincts were relentless and fresh. And before he completed his First Symphony in 1934, Popov was already an experienced composer for the film. The radical nature of his music was fueled by the teachings of his professor at the St. Petersburg (then Leningrad) Conservatory of Music, Vladimir Scherbachov, who himself was caught up in the mood and experimentation of the time and achieved fame with his "Blok" Symphony. His associations with a legendary film director, Vsevolod Meyerhold, had further influences on his music which is noticeable in this remarkable creation. Popov's First Symphony (1928-1934) is extraordinary for its unrelenting creative impulses yet with a keen sense of structuralism. As with, say Lyatoshynsky's Second Symphony (1935- 1936) and even his Third much later, in 1951, this work contains polyrhythms and simultaneous orchestral clashes that captured the spirit of the times, even when the age of experimentation was diminishing after 1931 (the various imitative polyphonic devices used in these works and others were symbols of artistic defiance). It is quite remarkable that even Lev Knipper, a founding father of the Russian Avant-Garde, happened to write the Fourth Symphony in 1933, which is perhaps the most socialist-realist work ever. But Popov's First is as honest as it is stubborn, the testament of a creative genius who refused to go down without a fight. As with Shostakovich Fourth, Popov's masterpiece represented disquieting struggles against the increasing weight of the enforcement of Socialist-realism policies and principles. Knipper gave in then rebounded much later while Shostakovich did not. Popov's fought on, but strained emotionally and artistically in the end (the abhorrent 1948 Zhdanov Affair presented him the final blow from which he could not fully recover). But, if anything, the masterpiece show's the unyielding fight for artistic freedom amidst the changes and the increasing atmosphere of fear and subversion that were going on around these artists and their admirers. If Shostakovich's delightful Theme and Variations (1922) belies the instability of the new order (and its does, but refreshingly so), Popov's First Symphony does not. Roger Ebert once said in his review on the "Shawshank Redemption" that "all good art is about something deeper than its admits." The good art, in Popov's masterwork and Botstein's rendition of it with his excellent orchestra at his disposal, went deeper, and not ashamed in the slightest bit in admitting it." Perplexed by Popov Russ | Richmond, VA | 11/26/2006 (3 out of 5 stars) "For me, this is a difficult disc to review. Listening to the first symphony (1934) of Soviet composer Gavriil Popov (1904-1972) is quite an undertaking. And, I am not really referring to the length (although, at 50 minutes this is not a short work), but rather to the unrelenting harshness of the symphony, as well as the aimless direction the work seems to take on its long journey.

Popov is not really household name, so it is partially helpful to refer to other, better-known composers when speaking of Popov's first symphony. Implicitly, a connection to the works of Shostakovich (1906-1975) is made by coupling Popov's first symphony with Shostakovich's Theme and Variations. This connection is made explicitly by the program notes, which lists in great detail all of the similarities between the lives of the two composers. Parallels are also drawn between Popov's first symphony and Shostakovich's fourth symphony. While it is true that both works date from the 1930's and that neither was approved by the Soviet authorities, it is far too simple to state that if you like the early works of Shostakovich you will like Popov's first symphony. The point is there are probably more apt comparisons to be made. The opening orchestral outburst sounds like Stravinsky, while the clamorous coda of the symphony sounds like a more cantankerous version of Scriabin's "Poem of Ecstasy." Part of the scherzo reminds me of the opening of Prokofiev's "Scythian Suite" without the memorable melodic material. I am not quite sure what to make of the lengthy inner section of first movement, or the entire second movement, but possibly there are traces of Schoenberg and Messiaen here. So I suppose the conclusion to be drawn here is that, for me, Popov's first symphony is quite a mix, and not all of the ingredients are to my liking. However, if this bizarre blend sounds appealing to you, this disc may warrant your attention. But I suppose a more direct approach can be taken in describing Popov's symphony. It is a three movement work, consisting of a incoherent 24-minute opening movement, a plodding 17-minute largo and a relentless 9-minute scherzo and coda. For me, most of the problems occur in the first two movements, which arise from the harshness of the texture, the lack of memorable melodic and harmonic material, and from the kaleidoscopic approach to form. At any one point in the symphony, I really can not indicate where the work is going - or where it has been, for that matter. So, going back to Shostakovich; I would say that the large and complicated nature of Popov's first and Shostakovich's fourth, as well as the political intrigue and oppression taking place at time of their composition allows one to state that both works are symphonies of musical "interest." Yet, the propulsive energy, emotive communicativeness and distinctive melodic material found (to a greater extent) within Shostakovich's fourth leads me to conclude that while many will find Shostakovich's fourth to be of musical "merit" relatively few will have the same feelings for Popov's first. This disc concludes with the only available recording of Shostakovich's 15-minute Theme and Variations, composed during the composer's sixteenth year. This is a very early work and the influences of Tchaikovsky and Glazunov loom large (especially the work's festive Glazunov-like conclusion). With that said, there are moments that look ahead to Shostakovich's ballets and the work also contains a beautiful largo variation toward the end. So, I suppose I am back where I am started. This is a difficult disc to rate. Everything is well-played and recorded, but I do not believe I will return back to the Popov symphony often. Primarily on the basis that I did not like the Popov (except for some parts in the third movement), I am giving this disc three stars. Nevertheless, if you consider yourself highly adventurous and enjoy musical oddities, there may be something here for you. TT: 65:24" |

Track Listings (18) - Disc #1

Track Listings (18) - Disc #1