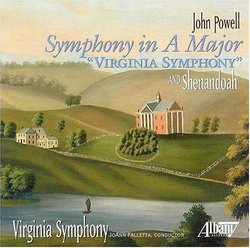

| All Artists: John [Piano] Powell, American Traditional, JoAnn Falletta, Virginia Symphony Title: Symphony in A Major: Virginia Symphony Members Wishing: 1 Total Copies: 0 Label: Albany Records Release Date: 6/24/2003 Genres: Folk, Pop, Classical Styles: Vocal Pop, Opera & Classical Vocal, Symphonies Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 034061058922 |

Search - John [Piano] Powell, American Traditional, JoAnn Falletta :: Symphony in A Major: Virginia Symphony

| John [Piano] Powell, American Traditional, JoAnn Falletta Symphony in A Major: Virginia Symphony Genres: Folk, Pop, Classical |

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD Reviews"The Virginian" P. Bryce | MD USA | 12/08/2005 (2 out of 5 stars) "This recording presents something of a mystery. My prior experience with this work comes from a c.1982 performance of an "abridged" version by the National Gallery Orchestra conducted by Richard Bales (the present disc is the very first commercial recording). Bales was a superb conductor and a good composer himself, who remains unappreciated outside of the Washington metropolitan area. Above all, he was an ardent champion of American music, with such credentials as the premiere performance of Ives's First Symphony as director of the annual American Music Festival at the National Gallery of Art. He must have had a special fondness for this work of a fellow Virginian, since he had great interest in music similar to the sources of its themes. It is unfortunate that the wider world will come to know this grand work by the workman-like interpretation of Joanne Falletta and a regional orchestra, which, though competent, could never equal Bales's fine band. This performance merits most of the faint praise this disc has been damned with, but none of a lot of the other nonsense that has appeared about it in published reviews. Reviewers have claimed that this is more a suite than a symphony, that there is no contrast in the movement tempos, that there are no memorable themes, that there is not even competence in stringing those together that it has, and that the orchestration is inept. Comparing the CD with an aircheck of the Bales performance revealed all this to be utter rubbish and to call into question the very text of the score, itself. The solemn theme that opens the final movement on the CD is instead the opening of the symphony on the Bales version, thus negating the complaint of one reviewer that there is no thematic relationship between its four movements. This is not true to begin with, but the return of this theme in the central part of the last movement neatly negates any such contention. The two central movements are reversed in the Bales, the Allegretto being placed third, not second, again neatly answering the criticism that there is no fast movement, only two similar-tempo movements without enough contrast. This is Falletta's fault. One of the movements is marked Adagio, the other Allegretto. She may take them at the same speed, but Bales delivers a true Allegretto. And then there is the matter of orchestration: distinct parts for snare drum, gong, glockenspiel and a guitar or mandolin, all can be heard in Bales's but are completely absent from Falletta's. In Bales's hands there is true symphonic sweep. Bales's Adagio reminds one of nothing less than a movement from a middle-period Vaughan Williams symphony, and a worthy one at that. And it is hard to miss the similarity of certain passages with Vaughan Williams's Folk Song Suite. And why not? Powell's themes were said to have been gathered on musicological field trips in the Appalachians similar to the ones Vaughan Williams undertook in Essex and Sussex, from which he developed a distinct preference for the modes in his writing. Powell's materials are based on Anglo-American modal tunes that derived directly from the British Isles via our first colonists. In fact, the full name of this symphony is "Symphony on Virginian Folk Themes and in the Folk Modes." Bales billed it as simply "The Virginian." But strangely, no one seems to be able to identify any of Powell's source material, even though his ethnographic music collections reside at the University of Virginia, leading to the possibility that they may actually be original and only inspired by his researches. Wherever they came from, Oh! what great tunes they are! The Allegretto alone, with its two lilting melodies puts the lie immediately to the notion that there is nothing memorable in Powell's themes. Other composers should have been so fortunate to work with half so much appealing material. Derived or inspired by folk ballads, southern folk anthems and rural jigs, reels and banjo tunes as it is, this is no pastiche. The tunes are worked out and woven together as skillfully as they are in Vaughan Williams's or Holst's more famous folk-derived compositions. The final movement and its almost Elgarian coda is a noble climax, with a devout and solemn chorale intoned by the brass choir taking a central position, while jigs and reels entwine around it. This is really a grand passage in the Bales performance, but passes by almost without notice in the Falletta. The Falletta runs 56 minutes to Bales's 48, even though Falletta takes consistently faster tempos in every movement except where she should in the Allegretto. This is because Bales "abridged" version snips at this and that, mostly repetitious material, to the huge betterment of the score's overall structure, while never cutting anything indispensable. So just whose work are we hearing in these recordings? The symphony was completed in 1945, but received an extensive revision and was first performed in that version in 1951. Are the differences those between the two versions? In my original review I speculated that it might have been Bales who made these changes, but I contacted the music librarian at the National Gallery and had him look into it. Through him I learned the version performed by Bales in 1982 was the world premiere performance of the version prepared by Roy Hamlin Johnson, long a respected professor of Piano at the Univerity of Maryland at College Park. Johnson was an advocate of Powell's music, worked with the composer, and made a recording for CRI of two of Powell's huge piano sonatas. Johnson has done a great service to the composer in all of his changes for the better and has created out of this wonderful material a work that could easily enter the repertoire. Apparently, it will never have that opportunity, as all evidence indicates the PC police have this disc under 24-hour surveillance. Half the lengths of the reviews of this disc repeat or elaborate on the facts mentioned in the booklet notes: that Powell was a founder of the Anglo-Saxon Club and had an interest in eugenics. (He was hardly alone in the latter in the 1920s of his maturity, when eugenics was widely promoted as a means of social perfection. It had many famous adherents, many of whom are still honored men of science and letters, including W.E.B DuBois). But without being told these facts, would anyone listening to this wonderful score suspect the composer of ever having had any but high-minded thoughts and ideals? That's just the point. Being a racist by today's standards does not necessarily disqualify you from writing beautiful, even noble, music in the first half of the 20th Century, and The Virginian is ample proof of that. But unsatisfied with the facts, these reviewers heap on falsehoods. David Hurwitz even stated that for Powell "anything African-American was strictly off the table." The truth is that he used African-American material in a number of his works, and that his most famous by far, his Rhapsody negre, which he performed hundreds of times during his career as a gifted concert pianist, was one of them (there have been several recordings of it, one available on a New World CD). Such sheer ignorance or willful deception disqualifies objectivity in writing about the music of John Powell, who one reviewer called "a shadowy figure in U.S. musical annals." Shadowy? He was for many years a professor at his alma mater, the University of Virginia (from which he took a degree in two years), had an important public career as a virtuoso pianist taught by the best of European teachers, and was well know for founding, and for many years running, the most famous folk music festival in the country in Abington, Virginia. (Sure, it was segregated, like everything else was in the South in those days). And the Governor of Virginia proclaimed "John Powell Day" in 1951 to show the State's appreciation for a lifetime of work by her native son in the Arts. But today, John Powell's now unacceptable beliefs seem to have condemned his art: "Powell will remain on the dark side of the American classical music pantheon," one reviewer predicted, even though his "world view" was shared by the large majority of his time, at least at some level. Objectively, though, that has nothing to do with his art nor should it interfere with your enjoyment of it any more than the fact that Wagner was a virulent anti-Semite should lessen or bar your enjoyment of listening to Tristan. Unfortunately, even if you can get past Powell's "world view," you can't really appreciate his art on this tepid recording. Listening to it you only get a faint taste of the thrill of a work that under Bales's baton was filled with succulent delight, ample inspiration, and yes, noble thoughts, all at the same time." A Romantic Symphony from 1951 J Scott Morrison | Middlebury VT, USA | 07/07/2003 (4 out of 5 stars) "John Powell (1882-1963) had an interesting career. Born in Virginia, taught piano by his married sister, Phi Beta Kappa graduate of the University of Virginia after two years, student of world-famous piano pedagogue Theodor Leschetizky in Vienna, he was a successful touring virtuoso pianist and an amateur astronomer who discovered a comet. He was also a racist who helped to organize the Anglo-Saxon Club of America which then helped pass a eugenics law, whose aim was 'racial purity,' in Virginia in the 1920s. Ironically, Powell's most successful orchestra work was his 'Rhapsodie nègre' for piano and orchestra, based on African American themes. Perhaps his most important work, still not completely evaluated, was his efforts as an ethnomusicologist in the southern Appalachians. Some of the tunes he collected made it into his works, including the orchestral 'A Set of Three' and the once-popular 'Natchez on the Hill,' based on Appalachian fiddle tunes. He also wrote three very good Lisztian piano sonatas, two of which, played by Roy Hamlin Johnson, are still available on CRI.His only symphony, written in late 19th century musical language and recorded here, was composed in 1945 and extensively revised in 1951. He called it the 'Virginia Symphony' and it is based in large part on tunes he collected in that state. Composers who base their works on folk melodies and dances usually have memorable tunes to work with, but that is not always the case here; only a few of them stick in one's mind. Not one of the tunes is familiar to me, and I gather that since his huge collection of folk music has never been annotated, they are unfamiliar even to specialists in the field. It would probably be fairer to call this symphony a folk-song suite. That is to say, symphonic procedures are not in clear evidence here. Still, there are four movements - fast, slow, slow and slow/fast - as in many symphonies and I guess Powell could call the piece whatever he liked. In practice, however, what we have is a number of tunes strung together--expertly, I'll grant you--rather like Vaughan Williams did in his 'English Folk Song Suite.'The first two movements are by far the strongest of the four. The first movement is based on lively Scottish-sounding tune, sometimes accompanied by Brucknerian horns; late Romantic harmonic sequences are much in evidence, and there is some contrapuntal combination of a couple of themes. The second movement is a set of variations on a slow 6/8 strathspey with a middle section that uses a tune with a Scotch snap. That middle section has some delectable wind solos and I would particularly single out the playing of the English horn and principal oboe. The third movement, also slow, starts propitiously with a long mournful melody in the violas, but then introduces one unmemorable melody after another building again and again to overheated climaxes. The fourth movement has a long slow introduction that eventually leads to a series of quick reels that are ultimately combined, sometimes 6/8 against 2/4. It is interesting enough but overstays its welcome with some mechanical-sounding climaxes. For what it is--namely a late Romantic piece using procedures that would not have been out of place fifty years earlier--it works reasonably well. But it is not a masterpiece by any means. And it is probably fifteen minutes too long.The performance here, conducted by the extremely talented JoAnn Falletta, is all one could ask. The level of musicianship in regional American orchestras amazes me again and again. I've recently heard terrific performances by orchestras from Delaware, San Luis Obispo [California] and Albany, and now this one from Hampton Roads, Virginia. We really are in a golden age of American orchestral playing. The disc ends with a delectable (and straightforward) arrangement by Carmen Dragon of 'Shenandoah.' It is played gorgeously by the Virginia Symphony's strings. (The players of the orchestra are listed--a move I applaud--and I noted that the entire first violin section in the Virginia Symphony is composed of women. All right!)Review by Scott Morrison"

|