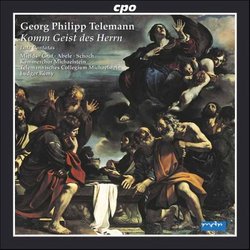

| All Artists: Georg Philipp Telemann, Ludger Remy, Telemannisches Collegium Michaelstein, Dorothee Mields [or Blotsky-Mields], Knut Schoch Title: Telemann: Komm Geist des Herrn Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Cpo Records Original Release Date: 1/1/2006 Re-Release Date: 7/25/2006 Genre: Classical Styles: Opera & Classical Vocal, Historical Periods, Baroque (c.1600-1750) Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 761203706426 |

Search - Georg Philipp Telemann, Ludger Remy, Telemannisches Collegium Michaelstein :: Telemann: Komm Geist des Herrn

| Georg Philipp Telemann, Ludger Remy, Telemannisches Collegium Michaelstein Telemann: Komm Geist des Herrn Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsAbsolute Mastery of Form Giordano Bruno | Wherever I am, I am. | 08/31/2009 (5 out of 5 stars) "Georg Philip Telemann (1681-1767) and JS Bach (1685-1750) were explicitly rivals only once, and Telemann won. In a sense, however, they were implicitly rivals throughout their contemporaneous careers, and the rivalry was 'no contest'. Telemann was the most celebrated German musician of the age, held choicer posts, got more lucrative commissions, enjoyed more ample resources for performance, heard his music performed more skillfully and for more appreciative audiences. Were those audiences blinded to real excellence and therefore obtuse to Bach's genius? Or was it just luck and happenstance?

The comparison isn't straightforward. The two men, based on their situations, expressed themselves in different genres. Bach wrote his sublime unaccompanied violin and cello suites and his unrivaled keyboard masterworks; Telemann wrote operas and concert-hall oratorios. In one genre, nevertheless, they both produced an enormous repertoire of glorious moving music that was performed almost perfunctorily and thereafter neglected or lost. That genre was the workhorse sacred cantata intended for 'Sunday' worship services in church. The large majority of Bach's surviving cantatas fit this genre, and their immense acclaim in our times -- there are at least half a dozen 'complete' recordings of them on sale today -- would have flabbergasted the congregations that heard them inattentively in their baroque churches. Telemann's church cantatas haven't gained such a following. Not yet, anyway. The three sacred cantatas recorded here should reveal instantly that Telemann and Bach were writing very similar music, in the same German Protestant musical language they'd both inherited from Buxtehude, Kuhnau, and in fact older Bachs. And they were composing, both of them, with fabulous inventiveness and contrapuntal mastery. The vast majority of listeners, including the humble violists and bassoonists who perform them for a living, would be hard-pressed to detect a difference of quality or even to decide whose work a given cantata was, in a 'blind' comparison. In fact, several cantatas ascribed to Bach by 19th C musicologists have proven to be Telemann's. "Komm Geist des Herrn" (Come, Holy Ghost) is one cantata about which we know quite a lot as a result of a controversy between the composer and a prominent clergyman. The cantata was performed on Pentecost in all five of the major parish churches of Hamburg in 1759. The brouhaha concerned Telemann's use of a revered chorale text written by Martin Luther but revised by the living poet Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock. Ach Himmel! Donner und Blitzen! What a radical that Telemann was! Pentecost is the celebration, a major one for Lutherans, of the manifestation of the 'third person' of the Trinity, the Spiritus Sanctus. Telemann's music is ample in every way, an unusually extended ten-movement proclamation of spiritual Good News, complete with trumpets and tympani, four soloists, chorus, and orchestra. Musical variety abounds, yet the work has complete unity and a sense of developing drama. Telemann was a more thorough master of the larger form of the cantata, possibly because of his theater experience, than his provincial Saxon rival. This cantata, IMHO, also matches anything written by that other towering German, il Caro Sassone, in his London exile. The highlight for me is the duet before the final chorale, an example of crafty counterpoint, chromatic daring, and expressive modulation. "Kaum wag ich es" (I hardly dare...) is known to have been performed at ordinary Sunday worship services in 1762, but the text is exceptional. Rather than the normal compilation of well-known devotional verses and familiar hymns, Telemann chose to set the entirety of a poem by a young friend, the local literary lion Johann Joachim Eschenburg. Much as the chorale melody might sound like a good old Lutheran hymn, it wasn't one; Telemann composed it in its almost archaic perfection to suit his poet's words. Since the poem is completely strophic, there's no recitativo in this cantata. Instead we hear the chorale, four solo arias, and a reprise of the chorale. The arias offer a remarkably clear succession of emotions, first despair, then penitence, then confusion and bewilderment - all in the voice of a sinner - and then soothing encouragement in the voice of the Redeemer. The cantata concludes with a chorale of grateful confidence. "Er kam, lobsingt ihm" (He came! Sing praise to him) is another demonstration of Telemann's mastery of the whole form of the cantata. Once again, there is no recitativo. The four soloists sing five freely-structured solo arias -- bass, alto, tenor soprano, bass -- without 'da capo'! They are followed by two choral movements, the first contrapuntal and the conclusion a fine rousing chorale. It's a bold stripped-down structure but scarcely 'minimalist' in its employment of instrumental color: three trumpets, tympani, two traverso flutes, oboe, strings, and organ. And if your musical instincts are religious, you'll hear the glory of the Ascension in every note. Recorded in 2006, this is one of the most polished performances of the Telemannisches Collegium Michaelstein, conducted by Ludger Rémy. The soloists are soprano Dorothee Mields, alto Elisabeth Graf, tenor Knut Schoch, and bass Ekkehard Abele. Ms Graf has a few moments of 'tolerable-but-not-perfect' tuning but the singing is rich in timbre and affect throughout. The Michaelstein chamber choir is bright in tone, well disciplined in attacks and diction, and excellently balanced. Kudos all around! My only plea for improvement would be that Maestro Rémy replace the hideous back-cover photo of himself smoking a cigarette and looking like a surreptitious survivor from the Baader-Meinhof gang. " |

Track Listings (23) - Disc #1

Track Listings (23) - Disc #1