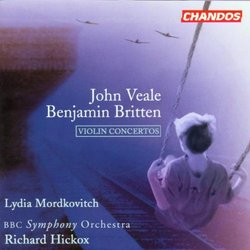

| All Artists: Benjamin Britten, John Veale, Richard Hickox, BBC Symphony Orchestra Title: Veale/Britten: Violin Concertos Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Chandos Release Date: 6/26/2001 Genre: Classical Styles: Chamber Music, Forms & Genres, Concertos, Historical Periods, Classical (c.1770-1830), Instruments, Strings Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPCs: 095115991022, 009511599102 |

Search - Benjamin Britten, John Veale, Richard Hickox :: Veale/Britten: Violin Concertos

| Benjamin Britten, John Veale, Richard Hickox Veale/Britten: Violin Concertos Genre: Classical |

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsBold Gestures from John Veale Thomas F. Bertonneau | Oswego, NY United States | 12/09/2001 (5 out of 5 stars) "It is unclear whether Benjamin Britten's Violin Concerto (1939) required a new recording -- although this is not to scorn Lydia Mordkovitch's impressively masculine account on the new Chandos disc. The cynosure of the program will nevertheless be the premiere playback-documentation of John Veale's (born 1924) Violin Concerto (composed 1982-84; premiered 1986), a work of brazen romanticism in the vein of William Alwynn and Lee Holdridge by a composer sidelined during the BBC's period of politically correct avant-gardism in the 1960s and 70s. Let me deal briefly with Britten. The Violin Concerto, with its companion-piece of a quarter-century later, the Cello Symphony, stands at the summit of Britten's purely orchestral oeuvre; it even forecasts the later score, having for its Finale a lengthy Passacaglia involving the soloist and orchestra in remarkable dialogue to impressive cumulative effect. But the First Movement (Moderato) is already arresting, with its quirky repeated rhythm of a quarter-note, a triplet, and another quarter-note, over which the violin traces a slightly Italianate melody at once supple and steely. The middle movement is a rapid Scherzo (Vivace), with a burlesque character that Lewis Foreman's commentary likens in texture to the music of Shostakovitch. I'd say that Britten's movement quite specifically anticipates the Scherzo of Shostakovitch's First Violin Concerto (1948). Shostakovitch admired Britten's music and one wonders whether he knew the Concerto. There is a good deal of acrobatic double-stopping in the solo part; Mordkovitch makes it seem easy. The question of Britten's influence on the Russian arises again in the case of the Finale, for the Shostakovitch Concerto likewise makes use of the passacaglia-form -- in its penultimate, core movement. As to Veale's Concerto: it is craggy, robust, and unashamedly accessible. No wonder the prigs disdained Veale back in the "revolutionary" decades! The First Movement, alternating fast and slow tempi, begins with crowded and slightly dissonant chords given out by the brass in march-rhythm; this marching figure vies with a contrasting lyrical subject, given at first to the strings, the two motifs seemingly related despite the differing aspects. When the violin enters (2.41), it borrows from both subjects, while the march (the composer refers to the "anger" that punctuates the movement) lurches heavily ahead. The solo part, while prominent, does not monopolize attention. In its First Movement, Veale's Concerto is very much a symphonic work with an important concertante part. In the Second Movement "Lament" (Largo), the relation of solo to ripieno corresponds more to the classical model. The strings-with-harp scoring of the opening paragraph inevitably reminds a listener of Mahler's Adagietto, and not only in instrumentation; but the solo part is refreshingly unpredictable, and not a little "modern," in its chromatic turns and wide intervals. Mordkovitch's execution of the pianissimo passages is particularly noteworthy, for she manages to be quiet and muscular at the same time. Concerto finales pose a difficulty, it seems, for contemporary composers, whatever their stripe. Nicolas Maw's Violin Concerto, also British and of recent vintage, boasts three effective movements and a rather forced Finale; so too with third and final movement of Veale's Concerto, although the music is lively enough, and Mordkovitch's playing gymnastic enough, to leave us impressed. The measure of this concerto is that it makes us want to hear more music by John Veale, who has to his credit three symphonies and a variety of essays in other genres. The engineering is typical Chandos top-of-the-line. Strongly recommended despite the stiff tariff. (Why in God's name did Chandos decide to raise its prices in a diminishing market?)"

|